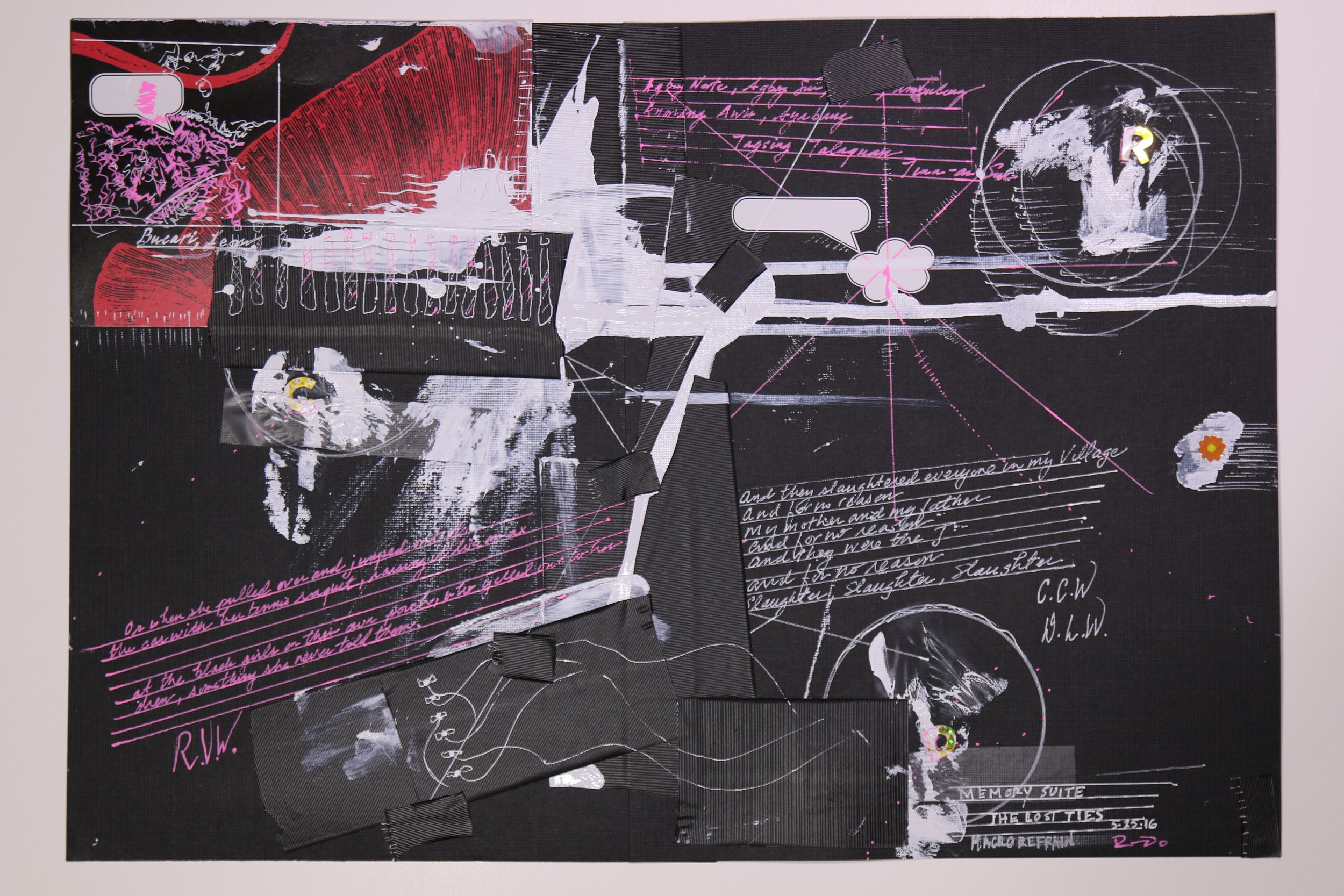

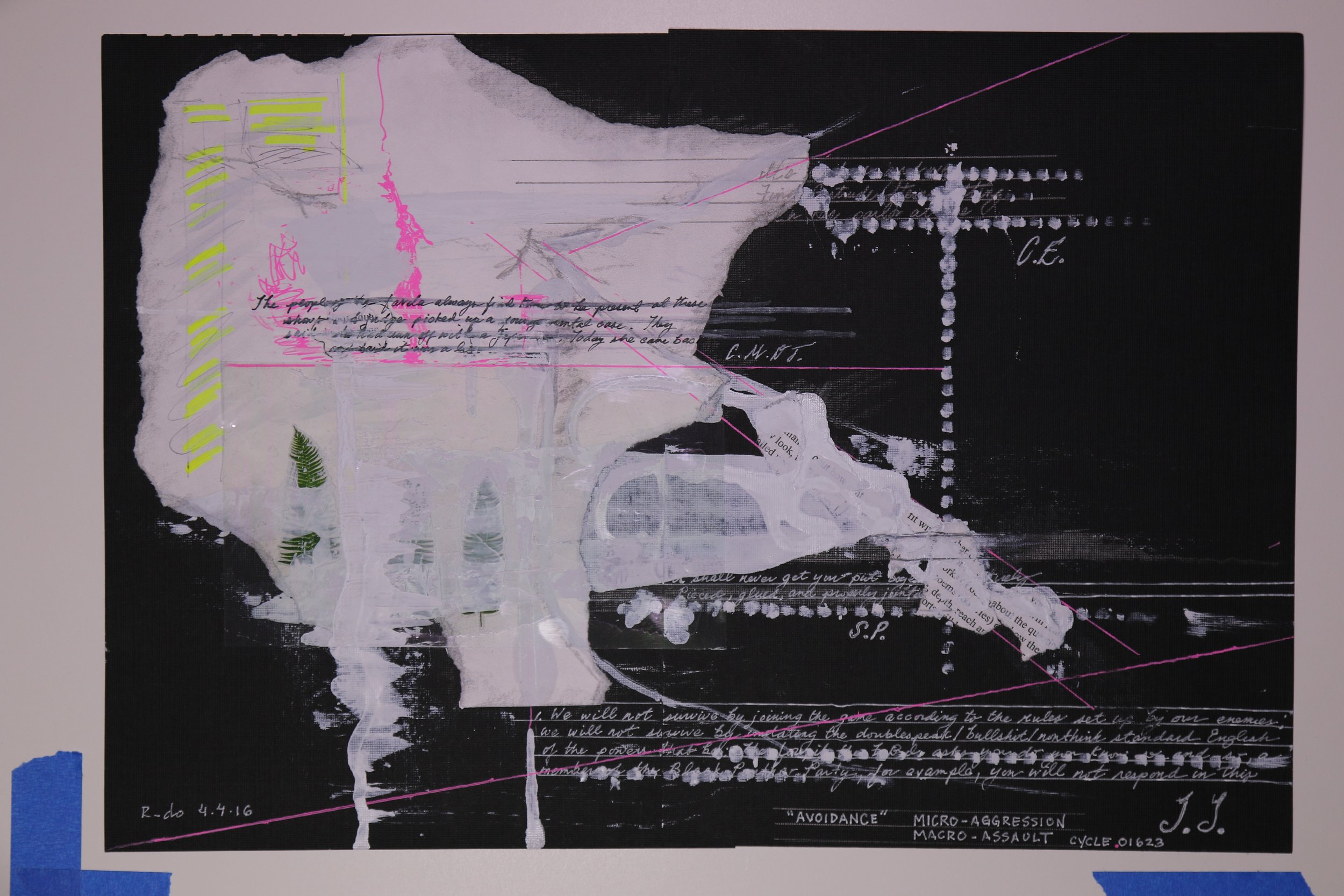

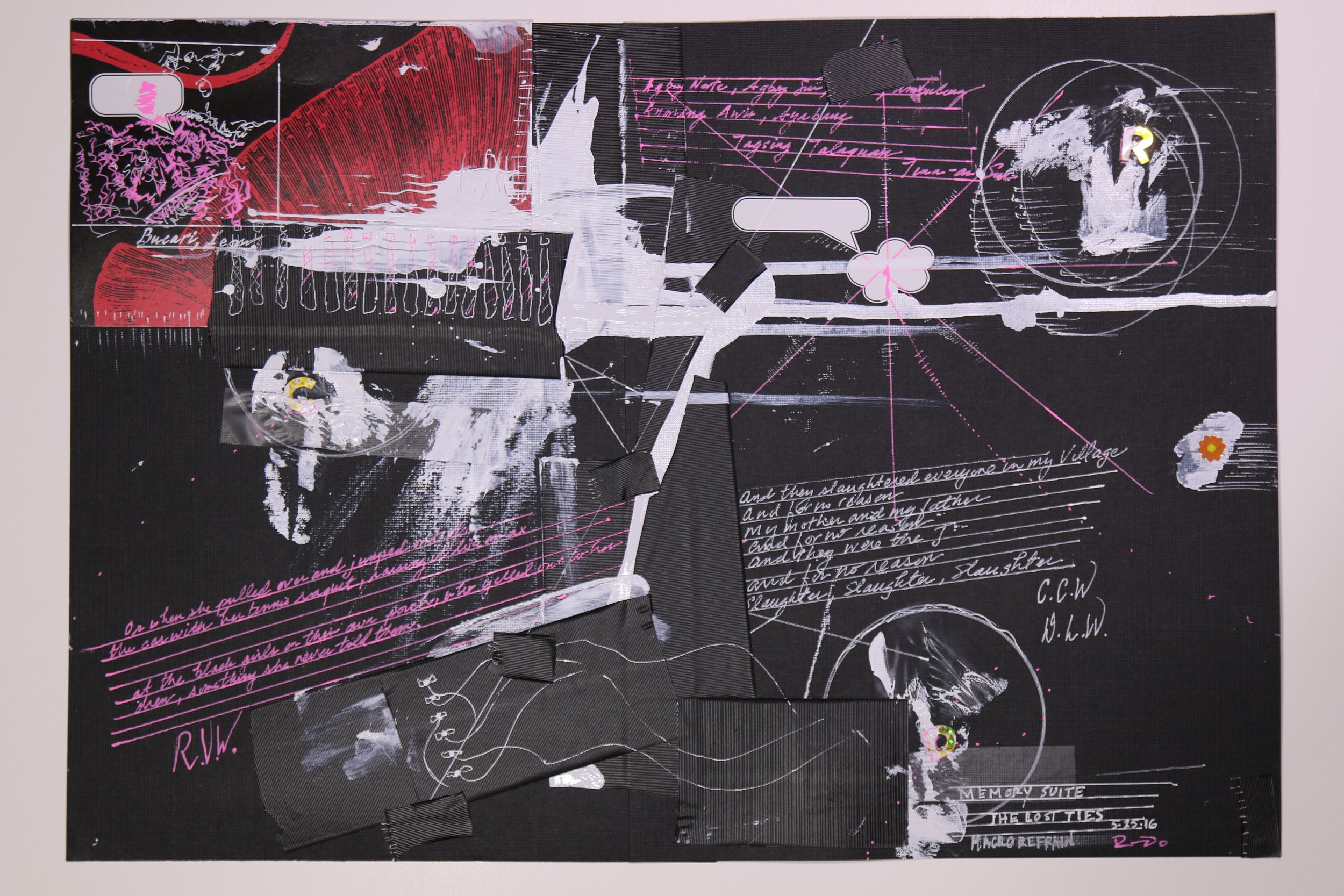

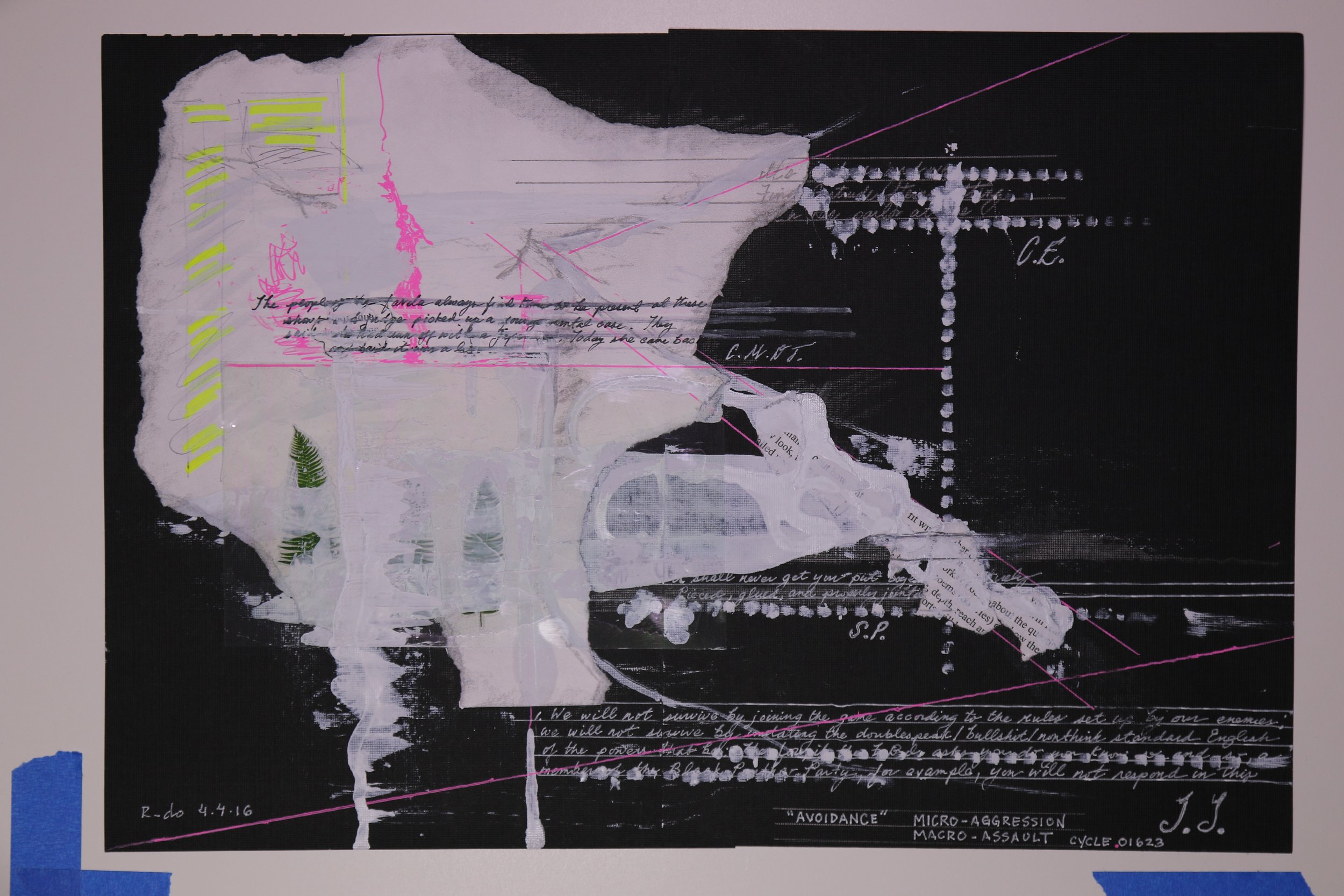

Cover Art

Your Custom Text Here

“Many today may not be aware of this, but the Black Arts Movement

tried to create Black Literary Theory and in doing so became prescriptive.

My fear is that when Theory is not rooted in practice, it becomes

prescriptive, exclusive, élitish.”

--Barbara Christian, “The Race for Theory,”

Cultural Critique, Spring 1987, U. Minnesota Press.

In my imagining Black The [Or] Y: Praxis, Sum Unknown for the Winter 2021 Issue of Interim Journal, my hope was to center, by way of open invitation, Barbara Christian’s call for a mode of Theory, which for me is The [or] Y—emphasis on the “or,” the Y axis, the vector, a range that spreads across and towards an alternative nexus of theory where generative praxis becomes possible among “people of color, feminists, radical critics, creative writers…for whom literature is not…discourse…but necessary nourishment for their people and one way by which they come to understand their lives better.”

And as I read, danced to, sung with, stared into, thought with and felt my way across the following works, beautiful in power, range, purpose, form, and discipline, I was excited to encounter and experience what happens when the press of such a call, now, successfully invites writers, thinkers, and artists to follow Christian’s timeless and essential lead into a radical clarity of remaining open, through her understanding of maintaining the vantage point and vivid enactment of a shared creative-critical horizon, that is, in Christian’s words:

“…open to the intersection of languages, class, race, gender in the literature. And it would help if we share our process, that is, our practice, as much as possible, since, finally, our work is a collective endeavor.”

And perhaps this was, and continues to be my hope, in bringing this selection, “a collective endeavor” of brilliant poets, fiction writers, translators, visual, sound and interdisciplinary artists, cultural critics, all radical thinkers and makers, together across forms, genres and disciplines in the spirit of Christian’s still urgent call for variety, multiplicity i.e. “that which is alive and therefore cannot be known until it is known,” until you say/write it.

It, is here. It, is now. It is—in these pages, across languages, screens, images, sounds, video, songs, sights, and beings. I am honored to have had the pleasure to receive and be in the company of this work, as an editor, and am now so thrilled and honored to share it with you, as I continue to think and live with these works, in conversation with one another, and with the power and generosity of Christian’s urgent and enduring call, again and again.

Ronaldo V. Wilson

Editor-at-Large

Interim Journal

Y the or, why

You or I

Yes or no

In or out

Pro or con

Hero or zero

The Y or X

Female or male, or other

Black or white, or other

The one or the other

Left or right

Life or choice

Able or unable

Legal or illegal

Fake or real

Rich or poor, wealthy or not

Paper or plastic

Half full or half empty

It’s true or it’s false

I agree or I disagree

I will or I won’t

My freedom or your freedom

Or fork in the road of Y or Y not

O eauiu o aiou ie o ae a o ai

i eey oie a i

o ue ouai aeie aoe e uie ai

i ea a eae i

Aeia Aeia o e i ae o ee

i i e aoie o iey

a o y oo i oeoo o ea o ii ea

e ou eoii ie i a e iei ie

e i eou ou a e oi ea

Black body Black books

Academic alien Artist ally

Reigning reactionary Radical resisted

Biological blueprint Break binary

Attack Africa Affirmation articulated

Repeating repressive Radical reclamation

Authority appalled Another approach

Coopted critics Celebrated creating

Humanists hegemony Hidden hieroglyphs

Repulsive reason Reading riddles

Institutions infiltrated lmagine intersection

Social stereotyping Sensual spiritedness

Theory takeover Theorizing today

Ignore insight Ideas influenced

Abstract assault Activity accelerates

Narrowness narratives Necessary nourishment

The curse of life as a prison guard tormented by a squalor of miscreants.

The capstone of lice as a periwig truncated by a semblance of mediocrity.

The cult of larceny as a pilferer tempted by a surplus of merchandise.

The creaking of leather as a pioneer tanned by a sunbeam of mortality.

The cocaine of lounge lizards as a piñata torched by a swig of mezcal.

The cartoon of Leviathan as a polka dot tricked by a simulacrum of mystery.

The consummation of lust as a primate tickled by a sirocco of metaphors.

The currency of lying as a profiteer tutored by a scholar of monetary policy.

The constancy of ligatures as a predator taunted by a stagflation of multibillionaires.

The cushion of lush life as a pornographer torn by a scalpel of misery.

The costume of legitimacy as a patriot trampled by a skinhead of manifest destiny.

The chemistry of Lilium as a pimple cream test marketed by a skimption of majority.

The curtain of languishing as a pipsqueak telegraphed by a signal of marginality.

What’s a me 2-4? What are you, me twofer?

Turn your tote bag inside out.

Shake up all the junk you got—

loose change, pencils, lipsticks, rings.

Take you off to get a brand

new bag to carry things.

Snatch a one-size sack, all black

faux leather with a sturdy strap.

Matches all your outfits so

anywhere it’s good to go.

What you use your me too for?

Put a bag over your head.

Yeah, that’s what he said.

Harryette Mullen’s books include Recyclopedia (Graywolf, 2006), winner of a PEN Beyond Margins Award, and Sleeping with the Dictionary (University of California, 2002), a finalist for a National Book Award, National Book Critics Circle Award, and Los Angeles Times Book Prize. A collection of essays and interviews, The Cracks Between, was published in 2012 by University of Alabama. Graywolf published Urban Tumbleweed in 2013. A critical edition of her poetry is forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press in 2022. She teaches courses in American poetry, African American literature, and creative writing at UCLA.

She couldn’t get in—he, not out—

until the frame was yanked to his left,

her right, halving him framing her: -eme

streaming “a sort of seventh son”

ofaybombed by the First “baboon in heels,”

okay uprooted by okra. They took a dive

and half: she went down on the 4th,

he, out cold as stripes declaimed the Tenth,

necessary, if predictive, stays

as the possibility of going

apeshit among the humans hanging

with a fifth chased by a forty

acre hold. Led by the light

from the deck, they climbed,

a king and his queen

about to be played.

Tyrone Williams teaches in the English and Race, Intersectionality and Gender Studies departments at Xavier University in Cincinnati Ohio, He is the author of several books and chapbooks of poetry.

In “Artifice of Absorption”[1] Charles Bernstein invokes Edmond Jabès in an epigraph that reads:

“Then where is truth but in the burning space between one letter and the next? Thus the book is first read outside its limits.”

Following this thinking, and moving to disrupt

the limits of genre and discipline, let us consider

the liminal as a generative space for critical production.

How different rhetorical registers, in their intersection,

can create a form in which to imagine potential alternatives.

A critical thought hurled to the ground

breaks into fragments. The dispersed multiples

gather a heretical prototype.

In suturing the bifurcation between creative and critical writing,

an amorphous text emerges. This is an introduction. A split tongue. A constellation

assembles such gestures into a multivalent “form” – a formless

form, a form against the formalities of form.

We form a counter-archive of small interventions.

A sample of critical essayistic analysis that gestures

towards a larger anti-genre to consider and further the work being done in

many different contemporary disciplines of archiving counter-narratives

and addressing the gaps within the archive.

We are interested in questioning the forms

and literatures we have been handed, how they have been integrated

into our social conditions, and how we might

activate an epistemological disruption.

What we are forming can take on

various names, a body inherently hybrid. This work is

not a move to commodify a genre but rather to acknowledge

an aberrant way of thinking critically. In its interdisciplinarity,

this provocation seeks to explore the boundaries of a critical

writing imbued with a creative approach. It embraces dissent.[2]

If we agree with Lukács that: “The forms of the artistic genres

are not arbitrary…they grow out of the concrete determinacy”[3]

then we can say that the cultural history of our poetic forms

becomes a history of social thought and practice.

Poetry is a conduit; and artifice– a possible technique for disruption.

Our current conditions require a new formation,

an interdisciplinary anti-genre that takes from

and goes against the idea of genre, cannibalizes

them to create something new.

We form a constellation of heretics who work

outside of and against the rigid forms of critical writing.

Consider our methodologies. The fragment is a space

that offers a dialogic exchange between archives, quotations,

and critical thoughts. It allows room for a speculative thinking

and a generative reading (both active and passive). It rejoices

in Keats’ “negative capability” and embraces paradox.

Bernstein writes:

“Why not a criticism intoxicated with its own metaphoricity,

… in which the inadequacy of our

explanatory paradigms is neither ignored

nor regretted but brought into fruitful play.”[4]

We embody a writing that revels. It is both

critically engaged and lyrical[5]. We inhabit a threshold

between research and poetry. At times we will be fully

present, at others a slight apparition. We are not alone in this work.

Criticism is here expanded to encompass multivalent forms

of critical thought. If we consider criticism to be a piece of

writing which is always addressing an object of critique,

this work adheres to the definition. However, the object

of critique here becomes something pliable, that can

be turned over, flipped upside down, inverted and fragmented.

Rather than argue for what Susan Sontag,

Bernstein and many other literary critics

have championed as a transparency in

criticism, we are more more aligned with

Edward Glissant’s call:

“to the right to opacity that is not enclosure within an impenetrable autarchy but subsistence within an irreducible singularity. Opacities can coexist and converge, weaving fabrics. To understand these truly one must focus on the texture of the weave and not on the nature of its components.”

Our project is inherently ambiguous

but in its impossible horizon lies its potential–

the invitation to explore different approaches and various

emerging methodologies in flux. Tracing Gertrude Stein’s

“continuous present,” historical texts are placed

besides and in conversation with contemporary pieces.

This is a move to dismantle hierarchies between them,

against canonical assumptions. Following a lineage

of the avant-garde (a word ambiguous in itself) –

our writing aligns itself with traditions

against the norm and hierarchy, and moves towards

what Marjorie Perloff calls “a language of rupture”[6].

By piercing our critical thinking, we can start

to texture our thinking in different orders. We can

refuse the forms institutionally imposed upon

writing, we can refuse to be legible within capitalism

and form a formless form.

[1] Charles Bernstein, 'Artifice of Absorption,' A Poetics, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1992).

[2] Bernstein, ‘Artifice of Absorption’

[3] The Sociology of Genres p79

[4] Bernstein, ‘Artifice of Absorption’p16

[5]The term “lyrical” can be ambiguous and amorphous, here the word makes reference to the lyric essay and the musicalities of prose

[6] The Futurist Movement: Avant-garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

Emma Gomis is a Catalan American poet, essayist, editor and researcher. She has published three chapbooks: Canxona (Blush Lit) and X (SpamZine Press) and Goslings to Prophecy cowritten with Anne Waldman (The Lune). She was selected by Patricia Spears Jones as The Poetry Project’s 2020 Brannan Poetry Prize winner. She holds an M.F.A. in Creative Writing & Poetics from Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in criticism and culture at the University of Cambridge.

Everyone showed up as a representation of themselves,

the hour underlit against a stark white screen,

inside the photograph, night was falling.

I texted myself, the discursive moment’s eating itself,

got back, “the discursive moment’s eating itself,”

got a text from an ex, “I love the shadow world more than thee,”

the shantytown up the street roared toward the end of history.

Make your senses not be mimetic,

“Make your senses not be mimetic,” ok!

Heav’nly Venus, illustrious, laughter-loving queen,

sea-born, night-loving, of an awesome mien,

pray prevent confusions,

ridiculously besot with their full meanings,

with cemeteries that exceed themselves.

In Paris, on screen, a of row women filmed one by one

appear dancing simultaneously.

Got back, “Words are markers with shifting occupants

in their corresponding graves,”

no reference,

lost reference.

Anne Lesley Selcer works in the expanded field of language. Their writing on, with, around, and underneath art has created a book of essays called Blank Sign Book, a book of poems called Sun Cycle, and a multitude of multiform publications, performances, and moving pictures. Most recently they have collaborated with artists to make off-page works based on their poetry. Girl is Presence, The Mouth is Still a Wild Door, and The Sadness of the Supermarket: A Lament for Certain Girls have shown at International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, The Moscow International Experimental Film Festival, Cork International Film Festival, The Berkeley Art Museum, Crossroads Film Festival, and ProArts, in addition to other places. Their poetry and art writing is in Prelude, Jacket2, Hyperallergic, Fence, The Chicago Review, and GaussPDF, and other publications, as well as several anthologies and exhibition catalogs. Sun Cycle won the Cleveland State University Poetry Center Book Prize, and their work also won the Gazing Grain Prize.

LEONORA M. PEREZ

1. That my mother walks walks walks in this state of wake is revelation itself.

2. That revelation itself: geographies in tension. Those geographies in tension: future-memories of narrations. Those narrations: transitions. Those transitions: a parking lot. That parking lot: a destruction of language. That destruction: an accumulation of content. That content: this slow construction of self. This self: a labor. This labor: a nurse. This nurse: Filipina. This slow construction of body in spatial and temporal traffic.

3. Traffic remains metaphor of interior. I walk in the history of my mother. I walk against grain of syllabus. I walk against promise of bibliography. I walk against inclusion. I walk against ruse of relevance. I walk against remaining traffic. And yes, yes, I walk against such metaphor.

4. And there goes my walking mother, a walking volta, in a post-shift trance, in white polyester nursing uniform, in black rubber shoes, in handcuffs covered by black sweater, my walking mother held by a blur of white men, held in violation, held in throat of world progress. I walk for the history of my mother.

5. Here are fragments thrown together—my mother's body is war, my mother's body is threat, my mother's body is collateral. And I, another genre of collateral.

6. Something fishy happening, my mother says. The FBI is here to arrest the suspected serial killer walking walking walking—the delicate crunch of gravel underneath her black shoes, cameras shuttering, slow traffic passing, a crowd of onlookers speculating, the sound of vein against skin, the sound of a history beginning.

7. History becomes black shoes and a white polyester nursing uniform within the context of racial capitalism. History becomes a black sweater draped over handcuffed hands at the mercy of imperialism. History becomes flowers checked for explosives in my mother's delivery room.

8. From which refusal emerges such History?

9. I refuse to follow you into knowing, and I leave you walking, mother, walking walking walking in the irrational.

10. Some stay working here for a sense of home, in fluidities of domination, in serial resistance, in hands undoing settler capitalism, a matter of realism draped over our very knowing. Amidst reporters everywhere, I walk against the ruse of innocence.

11. O, how serial is this crime, this white work in motion.

12. I walk at the history of my mother. And I believe in the disruptive role of her imagination.

13. The violence of news. Do not follow my mother into grave temporalities of racialization. Walk in gravel, walk against contribution, hold my hand as we walk through the history of my mother in the VHS cassette of Michigan, then Illinois, then Michigan again. Of this speculative history, I am suspect.

14. What remains muted in frame are the horrors of working white men just doing their jobs. Come with us, they say. Or we will drag you, they say. The silhouette of my mother passes; she holds in what most will never see. Here is what children do when everything done here is done against presence.

15. While underneath this scene there are alternative outlines, countermemories, underfutures. Here in the replay the ghost is not simply a dead or a missing person. We pray for the ghost. We are prey to the ghost. The underfutures ghost whatever we thought we desired in the first place.

16. What is the material history of the Filipina walking body, walking war, walking collateral, walking ghost?

17. I am a simple figure investigating where history indicts love. Love as roar, love as the ideology of underfire, a site in which I want to die laughing. I do not mourn the white scene. I do not mourn the white discovery of white regret. I suspect my mother does not tell me of the heaviness, of her own imperceptibilities. I'm so over description.

18. I walk against the history of my mother. I walk against legibility.

19. I walk directly alongside my mother, between those white FBI agents, inside the VHS of white Evanston. I walk against visibility, against articulation, and my mother says to me go ahead and smile, go ahead and cross the street: we stay delicate in our walking, perhaps shaking slightly, perhaps we walk through the epistemological break between history and fiction, and perhaps we become fiction someday.

20. We narrate against legitimacy, alongside the brightly archived rewind of image and volume of here not quite here and not quite bright, but open and slow, and my mother, I swear I swear, walks walks walks. There is merely something about you, walking walking walking, in front of a crowded anywhere, an anywhere that needs a theory. And the screen fades to black. Against a whiteness of timelines, against timelines of whiteness. And so I walk against state. I walk within the history of my mother who walks within a history of discrepant settlements, migrations, and fugitivities. We walk relationally, dear relatives. We walk, see, how my mother and I, still walk walk walk, without words, without propertied syntax.

NOTES

This essay reassembles language describing the scene of Leonora M. Perez's arrest as found in Jason Magabo Perez, "Because Love Is a Roar: Sketching a Critical Race Poetics," Entropy Magazine, 2018, personal conversations/oral histories between the author and his mother, and the independent film Yonie Narrates (2009), written and directed by Jason Magabo Perez. This essay is after Chrytos, "I Walk in the History of My People," in This Bridge Called My Back: Writing by Radical Women of Color, 4th Edition, edited by Gloría Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga (Albany: SUNY Press, 2015), 53. This essay samples, reconfigures, and draws its critical-poetic energy from the following lines, fragments, and sentences, and from the larger works within which they appear: "because your mother's body was war", "because love is a roar", and "because it is the destruction of language" from I Was Born With Two Tongues, "Letter to Our Unborn Children," Broken Speak (Asian Improv Records, 2002); "toward a countermemory, for the future" (22) and "The ghost is not simply a dead or a missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life" (8) from Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997); "The relevation iself may affect the narrator's future memory that happened before" (15), "That past has no content" (15), and "In other words, the epistemological break between history and fiction is always expressed concretely through the historically situated evaluation of specific narratives" (8) from Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995); "Geographies in tension" (149), "seeing the world only through meatphors of interior or contained spaces" (6), and "Recognizing this relationship is important for making sense overall of the processes and fluidities of domination as well as the varied forms of resistance required to address the ongoing consequences of mutable colonialisms" (10) from Natchee Blu Barnd, Native Space: Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism (Corvallis: OSU Press, 2017); "Here are the fragments put together by another me" (89), "A slow construction of my self as a body in a spatial and temporal world—such seems to be the schema" (91), "I wanted to kill myself laughing" (91), "here I am at home; I am made of the irrational; I wade in the irrational. Irrational up to my neck" (102), "hysterical throat of the world" (107) from Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, translated by Richard Philox (New York: Grove Press, 2008); "disruptive role of imagination" (77), "what is the material history of the Filipino dancing body?" (58), "descriptors of Filipino/a (racial) imperceptibility" (4), and "I interpret these historical spots of time as temporalities of Filipino/a racialization" (14) from Lucy Mae San Pablo Burns, Puro Arte: Filipinos on the Stages of Empire (New York: NYU Press, 2013).

Jason Magabo Perez (he/him) is the author of This is for the mostless (WordTech Editions, 2017) and I ask about what falls away (1913 Press, Forthcoming). Perez’s prose and poetry have also appeared or are forthcoming in various publications such as Witness, TAYO, Eleven Eleven, Entropy, The Feminist Wire, The Operating System, Faultline, Sonora Review, and Kalfou. Previous Artist-in-Residence at Center for Art and Thought (CA+T), Perez currently serves as Community Arts Fellow at Bulosan Center for Filipinx Studies, Associate Editor at Ethnic Studies Review, and is a core organizer of The Digital Sala. Perez is an Assistant Professor of Ethnic Studies at California State University San Marcos.

Micah Perks is the author of a short story collection, a memoir and two novels. Her novel, What Becomes Us, won an Independent Publisher’s Gold Medal and was named one of the Top Ten Books about the Apocalypse by The Guardian. Her short stories and essays have appeared in Epoch, Zyzzyva, Tin House, Kenyon Review, OZY and The Rumpus, amongst many journals and anthologies. She has won a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, ten Pushcart Prize nominations, the New Guard Machigonne Fiction Prize and residencies at the Blue Mountain Center and MacDowell. Micah directs the creative writing program at UCSC. She’s working on a novel about utopias. More info at micahperks.com

I’m sorry, I made a mistake. I meant horror. I said terror

Sorry, I made a mistake. I said terror. I meant error.

I’m sorry I said error, I meant theory, I meant pleasure. I am a late settler

on U.S. terrain, nearing Algonkian, Nonotuck land.

I find myself in an action/adventure scene—with a helmet, hazard gear, and supplementary

air—approaching

the bunker

of American interiority, a pricey

hermitage—accompanied by Bobby Day, the Bobolink drone. A radio geek, he breathes another

medium, teaches me the bop

through some rad headphones. I guess you could say we talk.

I say into my com: Hey Bobby, what’s the mission? Where do I start?

Bobby Day whispers: Hack the merle amerique,

the bird-come-down-the-walk, tweedle-lee-dad-dee of Emily D’s keep.

I turn on my bird display. I go: tweet, tweet.

Bobby Day sings: Go-bird-go.

Her forcefield’s a sizzling business, but cheery from afar. Now, bop-bop-bop onto the street.

I bop onto the perimeter

of the flashing circumference, scaling its kinks. I wear its terror font, its error font, its rockin’

robin font, a violation. My head blazes orange. I begin to crawl in shock.

Bobby Day says: Go-bird! Walk!

Then, I see her: Emily D with her endless bots and spy cams. Emily D with her nanotweaks and

tender-ware, her sender-worms, and gardens. Her emissions! Her royal arms! Emily D, 17,

buttoned-up and still, frozen in a spell! Hair parted in the center, glowing neon yellow! Perilous.

Emily D squared off, shielded like Fort Knox!

I see a neon-wet worm

emerge from the silt of her part. It slinks out to the verge where I stand.

Eat it, says Bobby Day,

and I eat the fellow raw. Bobby Day does

a high-resolution scan

of my gut morphology as the worm passes through, testing the bristles and ventral nerves, to get a

flavor of its lethal,

data-rich hue. My gut seizes up like graffiti! Bobby, I’m gonna spew!

Bobby Days says: Go-bird-go, vomit into the dew. Careful, now. She’s watching! Make like

you’re the Orient at Dawn coughing up the Sun.

Bop-Bop-a-Lu-Ow! Oh, Kat-man-du!

Her circumference crunches in, expands, out-bops me. I puke up a mischance,

unravelling my invasive,

alien scaffolding

onto the private, domestic sphere. I catch my toe in the skew. A jouissance

of flail and slant and sick.

Beep-beep-beep

Alarms go off at my awkward dance! Emily D’s

bots emit a chemical slew! Oh, Bobby I’m tripping, and running out of air!

Bobby Day sings: Go bird go. Go Switcheroo. Play the frightened innocent,

velvet sweet but scared.

Tweedle deedle dee, Tweedle deedle dum.

Maybe she’ll feel bad, and offer you a crumb,

to settle your insides, then you can hop on home.

Hop. Hop. Hop. Away. Plashless.

Mission done.

Vidhu Aggarwal’s poetry and multimedia practices engage with world-building, science fiction, and graphic media. Her poetry book, The Trouble with Humpadori (2016), imagines a cosmic mythological space for marginalized transnational subjects. Avatara, a chapbook from Portable @Yo-Yo Labs Press, is situated in a post-apocalyptic gaming world where A.I.s play at being gods. She has published in the Poetry, Boston Review, Black Warrior Review, Aster(ix) Journal, and Leonardo, among other journals. In her latest poetry book Daughter Isotope (OS 2021), she engages in a “cloud poetics,” as a way of thinking about personal, collective, and digital archives as a collaborative process with comic artists, dancers, and video artists. A Djerassi resident and Kundiman fellow, she teaches at Rollins College.

blue light in the mirror, the moon, and you

let gloom gleam like rot heath mired into

blues prosody mimics usurper dew

clit klitschnass drips snot, sheath gyred in two

axonemes, porphine moths’s teeth sunk into

the sea between us, luminous light, spumes

smithereens, slurred ovaltine sunken through

oceans, endorphins those lizard entombs

opium tongue stunned on starless night blooms

bruise blue, conjuring typhoon and monsoon

swallows we two as infinite night looms

consuming flame blue licks at honeyed moon

in gloom—we wend through—blood moon—doom—I see—

we bloom—vivisected—hope scorn’d—y’all’ll see—

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Refusing work is environmental justice

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Whitey’s on the moon like Gil and Sun said.

Sade LaNay is a poet and artist from 3rd Ward TX living in the NY Catskills. They are the author of I Love You and I'm not Dead, 2020 winner of the Lambda literary award for transgender poetry. Witness and support their creative work at seesade.com

Falling waves & full-throated fumes

do not care about you.

Blonde horses, bland

winds rise and do not

care about you.

Our sister does not

in her flushed face want

what you

want

at all.

--

There’s a light in a room three rooms away.

I’m not, I’m never, going to turn it off.

This sapling night’s just steeped in that dust

puddle. Message me. I’m staying here

in the green green

of under.

--

Vodka-drenched

charcoal night—we

dance, our feet

gash

and stain.

through the glass door

my elbow

smells of lake and old navy boy

& dad in matching

T’s- I found a knife

from a different era

convenient store

water in my

car. all doors we’d thought we’d locked

slid open. the private bed was

broken in two

I had a child needed water

they always do – nothing has changed

most I know are still alive

but not all

how might I keep my kids at home, how might I keep them safe?

ask the dreamed women who

rape each other it was

freedom-day a day

like all days

to gather the lone ones in a

thunderous roll, holding hands everything talking running rain

through their hair.

the boy and his dad had slogans on their chests: the cops

love us. it was

father’s day (murderous) night, at least,

I said, they know how it works.

Julie Carr is the author of seven books of poetry, including 100 Notes on Violence, RAG, and Real Life: An Installation, and the prose works Objects from a Borrowed Confession, and Someone Shot My Book. Climate, a book of epistolary essays co-written with Lisa Olstein, is forthcoming from Essay Press. With Tim Roberts, Carr is the co-founder of Counterpath Press, Counterpath Gallery, and Counterpath Community Garden in Denver.

Ben Roberts is a cellist and composer living in Boston Massachusetts. He is a graduate of Cleveland Institute of Music and is currently a graduate student at New England Conservatory. Horse Cafe is Ben Roberts, Katie Knudsvig, Carson McHaney, and Kat Wallace.

[00003-AUDIO.mp3: 2pop tone followed by 4

sets of an exhale/inhale routine that gradually

lengthens.]

Solarfield Scrim

[00016-AUDIO.wav: rainfall or the white noise

of a boiling pot interspersed with mechanical

chirps, as of bats.]

Breeding Distribution

[00035-AUDIO.mp3: h old]

Land Lock

[00040-AUDIO.wav: rain on the roof, hard.

heavy coastal rain.]

Pipe End

[00043-AUDIO.mp3: the creak of a chair as

someone leans forward to get up, rubbing

flattened palms across knees.]

Plains Anatomy

[00056-AUDIO.wav: drrrrrmmm%%%%%

(as if elsewhere—a hallway?)]

Rain Hinge

[00057-AUDIO.mp3:

drrrrrrrrrrrrmrr=mrr==mrr===mrmr====

(as if there’s a fan pushing it)]

Pipe End

[00058-AUDIO.wav: ping ping thump & ping ping

& thump & ingingtump & gngngtmp ^^shudder]

Water Met

Amaranth Borsuk is the author of the poetry collections Pomegranate Eater (Kore Press) and Handiwork (Slope Editions) as well as three collaborative books of poems. She is associate director of the MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics at the University of Washington, Bothell. amaranthborsuk.com

Terri Witek's newest collection is The Rattle Egg (2021). Recent work has been featured in two new international anthologies: JUDITH: Women Making Visual Poetry (Timglaset, 2021), and in the WAAVe Global Anthology of Women’s Asemic Writing and Visual Poetry (Hysterical Press, 2021). Her many collaborations with artists and writers have been featured in performances, museum shows, and gallery exhibitions. Witek teaches Poetry in the Expanded Field in Stetson University’s MFA of the Americas with Brazilian visual artist Cyriaco Lopes, and their work together is represented by The Liminal in Valencia, Spain. terriwitek.com

for Meena Alexander

– ^ –

Hadi bakalim, come on, let's go.

Let’s pretend I know just how to build a home

that breaks these waves of false belonging.

And they are so warm and various -

the seats you pulled for me.

Just for a moment, let’s pretend, I know how to sit in those you taught

would never be of comfort.

--- The strange passage of a harbor

opens up. It fights all form and center ---

– ^ –

Enough, I said. You knew.

--- But then the sun became so bright against my thought

that language melted into something cosmic ---

So just for a moment, let’s pretend that I know all about the mirror --

and how resemblance is blood-streaked.

Let’s say I set my own eight eyes on the empty hand

that pulls us naked through the sky.

– ^ –

Come on. Let's go.

Let's find another room with better window access.

Let's talk about the ways you chose

to write about your blackness.

Because we're not so tired, are we darling?

We rise to write at 3am

with hopes of pleasant weather.

We are perhaps just one bright passage

of encounter -- some flickering

strength in flickering -- slicked oceans, new fragments --

This grief will never turn me into a better writer

I wrote, into my notebook -- ( Oh mushroom-headed city notebook

of water stone and wind, and I’m still not even sure how all

these haunted bugs of cold new light crept in )

-- but then I sent my words out farther.

after Daisy Atterbury’s writing and notes on my poem

– ^ –

I am looking for influence

and context. I have been repeatedly set upon this path,

although I reject it, although I must stubbornly reject

all the language that begins to touch my eyes.

Did I make it up, my eyes?

The self is a long symbol – self.

If self is true – if self is current.

– ^ –

I like blunt facts that accumulate in order to become sentiment.

Like lineage, like gender, like Frankenstein, or Drac.

I like where shame comes in as shame. I want the infection; I want

these formal voice shifts. I want the you question to be idiomatic; obtuse.

– ^ –

A strange sentiment erodes the narrative.

Erodes consciousness, erodes grip.

Like : language, language, language, lang.

It also erodes lang.

Our current quote of self is ‘thrash’

If self orders – look back ten.

– ^ –

My refusal to cite becomes : a cluster

and a child, posing as a father.

A false daughter becomes : fevers, intimacy,

and pornographic fame.

What are her locations?

– ^ –

Arrives : the you question.

Arrives : the question of you.

How will we treat these objects of study?

How will we find Dracula again?

– ^ –

She connects penetration with receiving. She connects receiving

with pain. She is noticing, she is academically admitting.

How else is this gesture occurring?

Else?

– ^ –

I write : you, voyeurism, void. A beingness

that won’t cohere. You, aparthood. You, the invariant.

You, a heart-shaped negation; a frame.

Close your values, close the sea.

If self is trailing –

please stop.

after Daisy Atterbury’s writing and notes on my poem

– ^ –

How romantic !

How people imagine academia, barbarism, dating other people’s libraries, the

quantum physics of jealousy, this strap-on as an idiom, the deeper knowledge

gained by finally – by truly – by sincerely

knowing nothing at all.

Here’s a good reminder : not everywhere is New York.

Here I am again soliciting a reader, although I stubbornly reject her. Here I am

refusing to reference, to be read alongside. Here I am existing (or not existing) in

the present. I am leaving the bar, I am constantly

in exit. An an an an. I am erasing the word an.

Whereas you – you build a world out of luxurious citation.

You evaporate through echo, vibe on distant meta-buzz.

You channel the wiser voice of explicit explication, you speak in holes

and then near-holes.

– ^ –

I spent twenty years learning that poems are not stories, are not

people, are not anything about.

Later on, the couples’ therapist turned to me and said :

Your feelings are all your own.

By controlling the terms, we imagine controlling

the scene that they are already carving.

– ^ –

The voice-over in this narrative is distracting. True or false.

Betweenness as opposed to nearness as opposed to subject

as opposed to what?

Negation and dissolution as opposed to admitting. False.

Sara Deniz Akant is a Turkish-American writer and educator. She is the author of Hyperphantasia (forthcoming from Rescue Press), Babette (Rescue Press 2015), and Parades (Omnidawn 2014). Her work has been a finalist for the National Poetry Series, and supported by the CUNY Graduate Center, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Willapa Bay, Yaddo, and Macdowell. She currently teaches writing at Baruch College, and co-curates the Kan Ya Makan readings series with Hala Alyan.

Dear Forgiveness, in the Second Year of the Pandemic,

Pantone Announces Ultimate Gray as Color of the Year:

after Katie Willingham

We are here in the twenty-first century and even technology has betrayed

my grief. Over lunch I learn a friend periodically searches Google Earth for

her dead father. There in the network: complicated code and pixelation, he

is still preserved gardening, not left to the afterlife like mine, not unfairly

relegated to a calendar square on an ill-fated commercial holiday, saturated

in candied and neon hearts, an annual reminder his fragile blood pumping

organ failed him. Pantone has proclaimed this year’s color Ultimate Gray,

has granted the general public an appropriate marker, dignity, solace and

space for their private dread, yet there is no announcement, no declaration,

target market analysis, trend forecasting consumer report, color authority

or proprietary shade for: Year of Ultimate Twin Aunt Suicide, Year of Ultimate

Attempted Abduction, Two Years of Ultimate Two Houses Burned Down, Year of

Ultimate My Father Dying in His Sleep, Valentine’s Day, My Aunt Dying, My

Younger Cousin Dying, My Friend Shooting Himself and How We Found Out via a

Celebrity Gossip Blog, My Grandmother Dying As I Arrived Overseas, Year of

Ultimate Garden Apartment Stalker, Year of Ultimate Automobile Accidents and

Uninsured Invisible Injuries, Year of Ultimate Domestic Violence Incident, Police

Report at the Station and Crime Scene Photographs, Year of Ultimate Second Trip to

Planned Parenthood, Year of Ultimate Layoff from Corporate Management Level Role

and Recession, Year of Ultimate Lawsuits and Chapter Seven Filing, Year of Ultimate

Losing Christopher and Hearing He Had a Baby with Another Woman Through Text

Message, Year of Ultimate Undiagnosed Mental Breakdown at Thirty and Selling My

Possessions in Exchange for Carry-on Luggage, Year of Ultimate Year That Followed,

Being Resigned to Silence and Hardly Speaking to Anyone at All, Year of Ultimate

Wrongful Termination Then Eviction, Year of Ultimate Discovering My Sister

Hoarding Exotic Parrots and the Eighties, Year of Ultimate My Mother Threatening

to Kill Me Again, Years of Ultimate Weathering Adolescence and Los Angeles. I have

already lived a personal pandemic, it lasted a decade, it was my twenties.

No one called and no one showed, there was no expertly stylized color

palette expressing a message of strength and endurance, and now I am

bored with everybody else's bereavement and losses. I tell my therapist I

hope they have everything taken so that someone might suffer as I have,

but my feelings are expired, outdated and inaccessible because today there

is language, a container, a color, bandwidth for sophisticated intelligence:

geo-browser able to access satellites and aerial imagery to memorialize their

difficult three hundred sixty-five days, smart machines, devices, tools to

catalog their temporary loneliness, missed birthday parties and girls’ trips,

deaths of co-workers, communities and households down the street,

uncomfortable conversations following unpleasant news cycles, virtual

funerals and Zoom wakes. I tell another friend I think society deserves this

and I do not feel except while watching the latest season of Grey’s Anatomy

Meredith's purgatory beach where she is reunited in weepy episodes with

all-time audience favorites, Derek Shepherd and Little Grey, and if I am

remembering right, her deceased parents, and residents and interns who

marked her pivotal platonic relationships. The primetime drama makes me

wonder who I want to encounter on my metaphorical death sand, makes

ugly crying between my sweats and sheets, tears disappointing to me at this

point. I decide no one. Dear Forgiveness, I’ve lost count of the people I have

disappointed, I’ve lost count of the people I am angry at, who I have

blacklisted, blocked, deleted, and while we're here, Dear Forgiveness, I must

confess how long I have resisted writing you, how long I have stayed in the

seven stages of rage, the mention of your name, syllables, spelling of

loosening, lessening, lifting, letting go angering me. I read online about the

guillotine slugs, Elysia marginata, who sever their heads for the sake of a

fresh body, one without disease of sadness and the past, meanwhile my

dear friend is somewhere strategically planning mailings and trying to

forgive her sick body since she cannot generate a new one, and I hunger to

pare myself free from generational curses, childhood trauma, the ten years

every relative who knew me as a girl spent dying and dying, too many bad

men, and why each holiday is tragedy for my family instead, my resentment

at the TV, how easily simpler women have brunch and belly laughs, cleave

my wrath towards partygoers, those romantics favored for Saturday date

nights, destined to celebrate anniversaries, pray I could reap the parts of

personality which render small talk impossible, somehow cut out all that

melancholy and dark, but what would I have left to show for it, would I

retain this parlor trick of poetry. How if I survived the violence of lacerating

others, then taking the blade to myself, in each incarnation my body will

still remain a middle-aged Black woman, modest, soft, and inevitably tragic.

Dear Forgiveness, do you believe in karma, in everyone eventually getting

what they have earned, given this means worldwide pandemic, is revenge a

gateway drug, are you distant cousins leading us to the same sugar slicked

shack in the forest. Dear Forgiveness, I admit that I hate the slugs, their

capacity for detachment, brave heads discarding faulty hearts and flawed

bodies, their leaving behind for a better version, their ability, and yes, their

willingness to believe a better version. Dear Forgiveness, please forgive me,

because I wish the friend’s father away, anticipate that day seven years in

the future when Google will dispatch its efficient clean energy vehicle to

reshoot the juvenile landscape of the lunchtime acquaintance, how in the

moment she will search as she has always, seeking confirmation, comfort,

or perhaps relief, the blemish of her ghost father perpetually pruning his

peonies will have vanished, computerized mourning replaced by the

updated street view: the glittering new housing development, the glint of

late model cars. I am struggling to forgive myself this delusion, this

contentment in the vision of his shocking absence, fingers frantic, typing

and retyping their address into the search bar. I see her clearly, terribly, feel

my blood rushing warm in speculation whether she will choose to save her

head heavy with yesterday, abandoning her sad innards and muscle memory

beside the now extinct coordinates, hue of her neighborhood amputated

from history, a digital ultimate gray gloaming almost in my imagination.

S. Erin Batiste is an interdisciplinary poet and author of the chapbook Glory to All Fleeting Things. She has received fellowships and generous support from PERIPLUS, Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, Rona Jaffe Foundation, Poets & Writers +Reese’s Book Club’s The Readership, Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, Cave Canem, and Callaloo. Her Pushcart nominated work has been exhibited in New York, is anthologized and appears internationally in Magma, Michigan Quarterly Review, and wildness.

I’m very proud and grateful to have been invited by Professor Taylor to remember Barbara Christian here today, with all of you; but I can’t help but feel that rather than me it should be one of my old schoolmates Gabrielle Forman or Sandra Gunning – eminent scholars who, like Professors Keizer, Livermon, Winters and Taylor and so many others, worked closely with Professor Christian. At the same time, I’m conscious of how it’s possible to be someone’s student even if you never took a class from them, even if your intimacy with them is confined to, but also released in, having tried to read them and to read along with them from the unbridgeable distance between Wheeler Hall (where the English department remains) and Dwinelle Hall (where African-American Studies used to be) and from the somehow more traversable expanse between, say, 1985 and today. Though I never took a class from her I was still able to work in the atmosphere Professor Christian somehow helped to sustain at Berkeley in the late 80s and early 90s and to work and study and play (a word she uses pointedly and to which I want to return) under her protection, which she enacted, only seemingly paradoxically, by leaving the Berkeley English department in the years immediately preceding my matriculation there. In leaving it, she didn’t leave behind the black students who came to that department in search of her and in her wake. Folks like Professors Gunning and Foreman, and Eleanor Branch, Keith Harris and Francesca Royster, and me, all engaged and remain engaged in various modalities of following in her footsteps, not only from Wheeler to Dwinelle, but also in those of Professor Christian’s footsteps that modeled an exodus we have sought and continue to seek to carry out and carry on, as a practice of abolition.

One way to understand Professor Christian’s refusal of the English Department is as a nonlocal instantiation of that same impulse that led the writer then called James Ngugi, along with his colleagues Owuor Anyumba and Taban lo Liyong, to call, in the late sixties, for “The Abolition of the English Department” at the University of Nairobi and, by extension, everywhere. At the same time, Ngugi’s and his colleagues’ assertion of a shift from a department of English to a department of literature branches from another shift Professor Christian had already been involved in before coming to Berkeley, when she and colleagues such as June Jordan, Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich – teachers of composition to the supposedly ineducable black and brown working class students of the City of New York, who tried to take advantage of open admissions to that city’s university – began to serve those students by finding the way back into the ground of literature, which is, as Professor Christian says, literacy, but a literacy immersed in sound, in orality and aurality and, more fundamentally, the general and generative sensuality of the shared experience of sharing. In that moment, as all throughout her career, Professor Christian bore the standard of a panafrican cultural insurgency that allowed, in her particular and special case, a flourishing exfoliation of literature in the wake of the digging, the tilling, the careful gardening of its conditions of possibility. Along with, but in a specifically feminist disruption and augmentation of her contemporary, Walter Rodney, Professor Christian’s groundings with her sisters and brothers and sons and daughters teach us how to read.

Though I am here, then, I hope, to represent the vast majority of her students, those who never took a class from her, I am blessed to be able to say that I breathed air that she made possible and that I heard the beautiful and critical and insightful sound of her own breathing on a special occasion or two, like the day when she delivered the lecture what we now know as “The Race for Theory” or the evening when she debated Ishmael Reed on the significance of The Color Purple, illuminating for him and for their audience the difference between Alice Walker’s novel and Steven Spielberg’s film. Of course, it has been for me and for most of us in her writing where the sound of her voice – so often attuned to the sound of our treasured writers as they record the sounds of the black social life they treasure – comes through in what she called “layered rhythm,” in a polyrhythmic complexity that demands her readers play with what she and they read together. This is how Professor Christian accompanies and complements Toni Morrison, refusing the distinction between criticism and fiction precisely in order to see how Morrison, in her turn, plays with, and against, Virginia Woolf and so that we, Christian’s readers, can join the choir she has joined and amplified, as it is itself in search of “the chorus of the community, living and dead,” that bears us and that we all bear, alive, unknown until its known in knowing. Listen closely to Professor Christian talking with Morrison until you’re ready to line it out and sound it out. Reading doesn’t get any more beautiful than this:

In your work, as in Virginia’s, inner time is always transforming outer time through memory. But since memory is not only individual, but merges with others to create a communal memory, outer time also transforms inner time. It is that reciprocity between the individual inner and the communal outer which your work seeks. The folk’s time, however, is not mechanical time, the march of years, which your chapter titles in Sula mock, but time, as it marks an event in human society but also in Nature, which for you includes the folk, as much as it means the seasons. The mythic quality of your worlds seems to be in opposition to many people’s concept of human history, when in fact history and myth have always been related, myth being a central part of any people’s history, history itself creating myth, time and timelessness in dialogue.

At her own unique but still ensemblic intersection of myth and history, Professor Christian brings the question of the world online. Right here, from everywhere we gather, at the end of this world and the beginning of every other, all the earthly way through the very idea, it’s cool to be together in the dis place/meant Barbara Christian plays. Right now, always, not sometimeish but timelessly, as we head off into the future in the present she still builds for us, Barbara Christian is right on time.

Remarks delivered January 25, 2021, in the Department of African American & African Diaspora Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. The occasion was a panel, “Barbara Christian and the Futures of Black Studies: A Roundtable with Her Former Students, Arlene Keizer, Xavier Livermon, Fred Moten, Lisa Ze Winters.” The panel was convened by department chair Ula Yvette Taylor.

Fred Moten works in the Departments of Performance Studies and Comparative Literature at New York University. His latest book, written with Stefano Harney, is All Incomplete (Minor Compositions/Autonomedia, 2021).

“This is a circus. It’s a national disgrace. And from my standpoint as a black American, as far as I’m concerned, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in anyway deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas. And it is a message that unless you kowtow an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the US Senate rather than hung from a tree.”

— Clarence Thomas, Senate Confirmation Hearing, October 12, 1991

Dear Kossola:

We have known each other for many years now. I do remember the moment we met, but I want to recall a time a bit later when you stood before an auditorium of students and chose to recount a story rather than to read from one of your many novels. You reminded us of why we write, the deep place of our storytelling past. This evening of your storytelling is significant because it was also an historic evening of an American election. Above and behind you on an enormous projector screen, a student technician had put up the changing electoral results as they were reported across the nation. Just as your story ended, blue splashed across those united states, and a mixed race son of a Kenyan father became our President. I remember your bemused face looking out from the podium at the ecstatic crowd, jumping from their seats, hugging and crying, cheering your story nested within another, well, another of your stories. Now we have together seen these years pass, the politics of the presidency now remade for reality television, dumped from any assumption or model of integrity or statespersonship into the success of a deal made that you cannot refuse.

Today, June 26, ten years later, the Supreme Court repudiated its previous decision on Korematsu versus the United States, that upheld FDR’s Executive Order 9066 incarcerating 120,000 Japanese Americans, my family included, during World War II, while, in the same opinion, upheld the Muslim travel ban, another executive order instigated by Donald Trump, calling for, in his words, “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” Justice Sotomayor, in her dissenting opinion wrote:

This formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue. But it does not make the majority’s decision here acceptable or right. By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu, and merely replaces one “gravely wrong” decision with another.

So you would say, stories repeat themselves, or we repeat the same stories again and again, and unless we change those stories, we cannot change our very lives. We hold in our minds and heart the assumptions of stories. But you also have a finely tuned ear for narrative’s linguistic challenges and the precarious meaning of meaning, the logistics of reason that can be useful for any endeavor, any story. But how dangerous it is to use these presumptions to judge, to make judgments that have consequences on the lives of others. The lives of others. This is not a small matter.

The basis of the Court’s decision today as concurred by five justices: Roberts, Kennedy, Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, rests on the government’s claim that the executive order does not mention “Muslims;” that countries like North Korea and Venezuela are also implicated; that waivers for undue hardship are in place on an individual basis; that this is about “aliens” who are outside of the United States; that the conditions of the proclamation will be reviewed every one hundred and eighty days; and that the President, for reasons of national security, has a right to protect the borders. On the face of it, it’s a rewriting of a previous version of the same executive order so that the original idea (banning Muslims from entry into the US) might be obfuscated from the text. The conservatives on the Court can now read and interpret the order with impunity because it does not involve the rights of American citizens nor mention the right of religious belief as guaranteed by the Constitution. That is, it’s not about you, but some abstract you, that is, an alien out there, a non-American in an un-GREAT-ful place. Its meaning should then be read for its “rational” words only. But, what story, indeed what executive order, has no underlying meaning, no context, no depth of thought, no history, no unreliable narrator? And what President and his appointed scriveners could be more unreliable?

The curious, though when you look at Thomas’s record for the past twenty-seven years, probably not so curious, addendum to this opinion, is Thomas’s concurring ten-page writ. It seems that Thomas decides to go further in his concurring opinion by questioning the authority of the lower courts to constrain the President’s authority by “universal injunction.” Now I might have this wrong, but I think he means that the District Court and the Ninth Circuit Court did not have the power to submit universal injunctions of the executive order to ban Muslim travel, that is, to stop it everywhere, nationwide. And then he proceeds to give us a history lesson that goes back to the eighteenth century and The Federalist Papers, and for that matter the English court system under a Crown pre-dating the founding of our country, to demonstrate the “judiciary’s limited role.” That is, Thomas would further limit the judiciary’s role to check the powers of the Executive—president or king, because that’s the way they did it back in the eighteenth century. This is, I believe, what they call an “originalist” or fundamentalist reading of the Constitution, as if its words can only be read as stuck in the past. So, the good news is that, just as the word “Muslim” does not exist in Trump’s travel ban, the word “slavery” does not exist anywhere in the Bill of Rights or the original Constitution. Thomas must have his court clerks scuttling around looking for original meanings; the historic details are dense, arguments summoning citations, citations summoning citations, twisting evidenciary linguistic logic. You could and have, as a novelist, made absurd the fictions of this as nonsense, but again, as you’re aware, real people will live the consequences.

But let’s go back to some original past events. We hang on the decisions of the Supreme Court because we believe our ethical understanding as a democratic people will there be adjudicated, that Dred Scott, or Homer Plessy, or Fred Korematsu, will have their day in court, and justice will prevail. I cannot however see how any judge or any judgment is devoid of politics; hanging onto an originalist interpretation of the Constitution is a strange justification, an arrogance of determining the rules, perhaps a way to sleep at night. And then there is the original past event of the Senate confirmation hearings, the cloud of Anita Hill and her young courage to speak. The parallel, not without differences, of Thomas’s and Hill’s lives are noted in their biographies: both raised in the South and influenced by familial examples of hard work and self-sufficiency; both recipients of policies of affirmative action; both educated in law at Yale; both headed to Washington DC, selected to work on issues of civil rights and equal opportunities. Thomas, confronted by Anita Hill’s allegations, never really answered his accuser, but rather lashed out at white senators and accused them of conducting a high-tech lynching. It worked. What remains of this story is the bizarre residue of a techno-lynching, Long Dong Silver, and a kinky coil of hair on a coke can. The speculative remains of this story is that, 27 years later, the person who replaced Thurgood Marshall on the Court has concurred with one politically conservative opinion after another and is poised to reverse opinions on affirmative action, voting rights, a woman’s right to choose, and to sanction the discrimination of another group of racialized people.

The heart of this story is the unrequited heart of hatred. Your narrator calls it pafology. Bigger Thomas kills a rat, then a white woman, then a black woman. He chops up the white woman and throws her into a furnace. Then he makes the black woman his accomplice, rapes and bludgeons her, and throws her down a garbage funnel. Along the way, he could have also killed a shopkeeper, his best friend, his mother, his mother’s pastor, a Jewish communist activist, the blind mother of the dead white woman, and any one of the reporters or police investigators. Defended by a white communist attorney who manages to blame this pathology on liberal white people, Bigger’s epiphany is that he can die knowing that freedom is embracing his violence. However any reader perceives the terrible anxiety of, shall we say, a lot of really bad choices, this is an awful book, but presumably it’s the book that Clarence Thomas said explains his psychological self. Franz Fanon aside, Thomas is, for better or worse, our native son. This is not good news.

Kossolo, how shall we crawl away from this fiction, recuperate our better sense of ourselves and of others? I invoke here, Richard Wright’s counterpart, Zora Neale Hurston, and the fictional figure of Janie Crawford, who sees God’s eyes watching hers. Living through two unhappy marriages to free black men whose property and accomplishments give her stability without love, she finally finds happiness with a gambler and storyteller who, in the end, she must kill to save. Life is not fair. Justice is finally political, and certainly not blind, not colorblind.

Kossolo, I am not writing to you for answers. Though perhaps you can merge these irreconcilable parts into whatever it is that fiction writers do. I only want to say that today I require a story that will release us from hopelessness.

And so,

Please take your ticket and proceed forward.

The voice is melodious to my ear. I can’t help but respond, Yo brother, don’t mind if I do. I wait for my ticket, but it doesn’t appear.

The machine hesitates, then: That’s some car you have there. Candy-apple red BMW 230i 248 turbo-charged four-cylinder, zero to sixty miles per hour in 5.3 seconds.

I stare at the machine, then look around for the surveillance cameras.

The machine continues impassively: Of course, you could have gone for the M230i turbocharged 3.0 liter inline-six; that babe lightning rockets to sixty mph in a second less, but that would be another ten thou. What’s another second? I’d say, brother, this is a good starter package for the newly tenured.

I could be hallucinating. It’s been a difficult morning. Ah, do you think you could give me my ticket and raise that arm?

Now hold on a minute. You started this conversation. You can’t just drive on by and park.

But this is a parking lot.

So it is. So it is. But didn’t you call me out?

Call you out?

You know, call me “brother.” I certainly appreciate it.

I think, okay, this must be like that Alexa thing. It responds to “brother.” I say with authority, Brother, open the gate now.

Not so fast. Not so fast. Plenty of appropriate parking spaces in here, give you all the room Manitoba needs to keep those pesky nicks and scratches far away. Besides you got the extended body plan.

I sit in silence, fuming. I glance at my Apple watch, search for my phone.

Brother, the machine continues, just settle down. It’s rare to meet another brother in this parking lot. And I got one helluva story to tell you.

I look in my rearview mirror. The cars are backing up behind me. What about them? I ask, pointing behind.

No problem, says the brother in the machine.

I get out of my car and walk over to confer with the silver Volvo. When she sees my face, I can see her fumble with the controls; her window rises to close, but I can hear her screaming inside the glass. What the fuck? Did you break it? A head pops out of the black Honda behind her, and he says, what’s the matter? I got tickets to see the matinee. Hey, he looks at me. Let me tell you how it works. You push the call button and get some help, see? Patronizing son of a bitch. The guy in a beat-up green Subaru behind him yells to the car behind, Move back! I’m backing outta here, can’t you see? The thing’s busted. Him and his overpriced sportscar, he waves at me. He had it coming! The woman behind him honks and yells, Hold your horses. I am backing out. Can’t you see? Now she’s yelling at me. It says it’s full! Full, you fool. I look at the signage: FULL. I point to the sign, shrug at the all the irritated drivers lined up behind me, and walk back to my car.

Micro-aggressions, the brother in the machine sighs. You have no idea. I get them all the time. Think about it. All those folks behind you, they used to be kids, cute babies and innocent children. You and me included. Now we are all in different stages of ugly.

I get back into Manitoba. The rearview mirror frames the cars behind backing out in various attitudes of hostility. Then, it’s quiet, and the brother in the machine begins.

If anyone knows my story, it’s the short version on the headstone with my name misspelled:

Louden Nelson

Native of Tennessee

Born May 5, 1800

Died May 17, 1860

Misspelled?

What would I know? I was illiterate. Signed my last will and testament with an X. What’s in a name given by a master named William Nelson? Except he named my three brothers Canterbury, Cambridge, Marlborough, and so I got to be London. Know what I’m saying?

London Nelson?

The one and only. And I might have come from Tennessee, but I was born in North Carolina. Hey, I can’t complain. At least I got a headstone. Below that is a plaque dedicated in 2006. Says I was born a slave and came to the California Gold Rush in 1849, secured my freedom, came to Santa Cruz in 1856, worked as a cobbler, bought a piece of land near River and Front Streets. Before I died, I willed everything I owned, 716 acres, to the Santa Cruz School District for the purpose of education. I am buried at Evergreen, an honored pioneer. This is mostly true. Local California history for fourth graders, but wouldn’t you like to hear the whole story?

I look purposefully at my watch, but the brother is on a roll.

Like I said, I was born on a midsized rice plantation in North Carolina along Cape Fear River in 1800, twenty-four years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence and thirteen years after that of the US Constitution. The master of the plantation, William Nelson, was a Tory loyalist for the British, but after their defeat at Moore’s Creek in 1776, old man Nelson tucked away his loyalty and in the intervening years only named his slaves after places in England. You might say that my becoming London was ironic.

Wait a minute, I interrupt the brother. Just to be clear about this, you’re telling me a tall tale, right?

Brother, what I’m about to tell you is all true as best as I can pull together the facts into true fictionalization.

I shake my head. I think about ripping that box out of the cement, but it stands there solid like London Nelson’s white marble headstone itself, and it keeps on talking.

Don’t you worry, what I’m about to tell you is pure poetry. Now, where was I?

Irony, I prompt.

Oh yeah. Not that there weren’t others in the vicinity who supported Cornwallis, but the Nelsons were set apart, shall we say. Sometime after the last of my brothers, Marlborough, was born, old man Nelson died. The oldest son John had already got his inheritance and started his own plantation some parcels away. Daughter Mary married and moved to Charleston. The next son Luke died in a hunting accident. That left Mark who got the land on Cape Fear and the youngest, Matthew; he got us. Matthew got the slaves. Matthew had enough of being set apart, the Patriot vs Tory thing, so he took himself, his widowed mama Fannie, and us – Canterbury, Cambridge, Marlborough, and me -- far away to Tennessee. Some said that Matthew got the raw end of the deal, no land, just slaves. But old man Nelson had some kind of plan to keep his operation insular. He made Canterbury his blacksmith. Cambridge got trained as a carpenter and bricklayer. Marlborough took care of the horses. I became a cobbler and I knew about planting. We all knew how to plant and raise small livestock. Matthew Nelson got us: the technology to start again. But let me be clear about this. We were still slaves, you know what I’m saying. The young Matthew Nelson put Canterbury’s son and Cambridge’s two daughters on the block as collateral to buy a sweet piece of land just outside of Memphis. Then the rest of us went to work, building and propagating and creating everything that makes what you know to be a plantation: white porch and Roman pillars, old oak spreading shade across deep grassy lawns, slave quarters, horse stalls with waiting carriages, cotton and tobacco as far as the eye can see.

Once Matthew Nelson set up his household with his mama Miss Fannie at the center, he got restless. He was only about twenty-something. Maybe a wife might have fixed that, but he started breeding horses, thoroughbreds to be exact. That’s where my brother Marlborough came in. Turned out Marlborough was part-horse himself, talked, ate, and dreamt horses, raced them to win every time. This went on for a streak, and then President Polk made it official: Gold in California. Master Matthew caught the fever, and by New Year 1849, he had a plan.

Not like we had a choice to go or not, but Marlborough and I got taken with the same fever with the idea that we could get our freedom. Canterbury was getting along in years, but he was still blacksmithing, making everything from hoes to fancy iron gate work. This was steady income for the Nelsons. They were like sub-contractors who kept all the money for themselves. Same with Cambridge who got sent out to build houses in town. And they had wives and other children and even grandkids. Marlborough and I had nothing but ourselves.

Canterbury drove us in the carriage to the port at Memphis, hauled out the luggage, boxes with picks and axes he’d made special. I remember he had a funny look deep in his eyes. He didn’t linger long, didn’t take to the clamor of the crowds, didn’t pause to notice Negroes chained together vacating the boat’s hull, didn’t wait to see how a riverboat could float away on steam. Even as we boarded the plank, he was turning the horses, following a paddy wagon full of caged black bodies. I stared over the deck at his hunched back, older but still powerful. In 1822, when we heard the news that Denmark Vesey had been hung, I saw Canterbury’s eyes grow wide and flood with tears, but when they dried up, I never saw him cry again, not when his wife Alyson died, not when his son Roger was sold. For him, I think life was a mean mistake. As the gigantic paddle began to churn and pull us away down the Mississippi, I thought I knew Canterbury’s premonition, but I heard Marlborough whoop like he did when he raced a horse over the line. So I let the sad resignation in Canterbury’s shoulders slip away from my own.

The machine goes quiet, and I think I can hear water cascading from the riverboat. I look forward and see the gate arm lifted. I say, What about the rest of the story? But the brother says, Please take your ticket and proceed forward.

Days later, I’m driving to Sacramento, and Manitoba decides to start talking to me, too. The voice pops out of the cyber satellite system, and it turns out it, too, is a brother. I think if I’m crazy, I’m crazy. Just pay attention:

You get into UC Santa Cruz on affirmative action. This was the 70s, and they wanted you. Your people came to San Francisco during WWII from Louisiana to get jobs in the war industry. Moved into emptied-out Japantown on Post Street and got to work during the day. During the night, they brought out their instruments and entertained themselves with the blues. That’s where you grew up. Harlem of the West. Fillmore. That’s where you got your musical education. On the streets, hanging out. Through the walls. In church. And there was the band at Galileo. Your instruments were brass with the Ts: trumpet, trombone, tuba.

Wait, I say, you are not talking about “me.”

No, it says, I’m talking about “you.” And he continues: In those days, no one thought about what was practical. Especially affirmative action colored kids. You were the ones with dreams. The revolution was gonna change everything, and you were gonna be there to be the change. You were not a militant Panther sort, mind you. You knew Huey hung out in Hist Con, his aide-de-camps standing around protectively, but you also knew Huey’s dream wasn’t exactly practical. Anyway, you were secretly in love with a white Jewish kid who played the saxophone.

I shake my head, turn off the system and drive to the motherlode in silence. After several miles, I call up my partner who lives on Long Island. I’m going crazy, I tell him. You were always crazy, he responds. But this is serious, I say. I can see him over there rolling his eyes. He asks, Do you know what time it is? I don’t, so I hang up.

Weeks go by. I park in the brother’s parking per as usual, have dinner a Laili’s, late movie at Cinema 9. Then, I proceed to pay for the ticket at the machine, and the thing perks up like yesterday. Brother, he says, accepting my ticket, I’ve been wondering what happened to you. Now let me continue my story:

At the tail of the big Mississippi River appeared the city of New Orleans. My memory is that it was busy and colorful. And in every corner of that pretty city, in high class hotel rotundas and public slave pens, colored people were on the block. I saw folks auctioned next to furniture and tools. I was born a slave, but I had never seen the actual commerce of it. Supposedly, Marlborough and I were going along to serve the master, but he could, in a pinch, sell one or both of us, if he fancied. Those nights in New Orleans, I rolled around on the floor at the foot of my master’s bed, while Marlborough slept curled up like a kitten. In the day, he wasn’t but eighteen. Freedom was a promise dangling from a long pole extended out there on the road before us. If we had known the road beforehand, would we have turned back? Turned out young master Matthew was anxious to leave too, didn’t want to wait two weeks for the next ship to sail around the Cape but booked a steamer for Chagres, convinced that cutting across the isthmus to Panama would give us a head start.

On the steamer, I met two Louisiana slaves who said their master was taking them to California to set them free. Was that the case with Marlborough and me? I kept quiet. It wasn’t wise to tempt fate. Night before we left Tennessee, Cambridge came to see me, gave me a small wood dog he carved himself. He rolled the carving around in his palm, probably remembering his two girls, got sent away with the same carvings. It was his warning; I kept it in my pocket. Then we got waylaid an extra three days in a storm somewhere out in the Caribbean. Folks on the ship were either sick from the rolling sea or sick from cholera, we didn’t know which. I figure the three of us were seasick because we didn’t die. Being seasick meant we lost the stomach to eat, and not eating must have saved us from catching that plague. Every day, one or two passengers or crewmen died and found graves in the sea. I said a silent prayer for the body of one of the Louisiana slaves slipping beneath the waves. I knew it wasn’t because he’d tempted fate; there was no difference between the two of us. Then the sea calmed, and as we approached Chagres, fish flew from the sea, and we managed to catch a few. Chagres turned out to be a bunch of grass huts with half-naked natives selling bananas, pineapples, coconuts, and oranges.