an interview

Lucy and RVW in the Studio

Part 1

Lucy: In Drake’s rapping, he asks: Is this real or fake?

RVW: What’s your infatuation with wanting to draw?

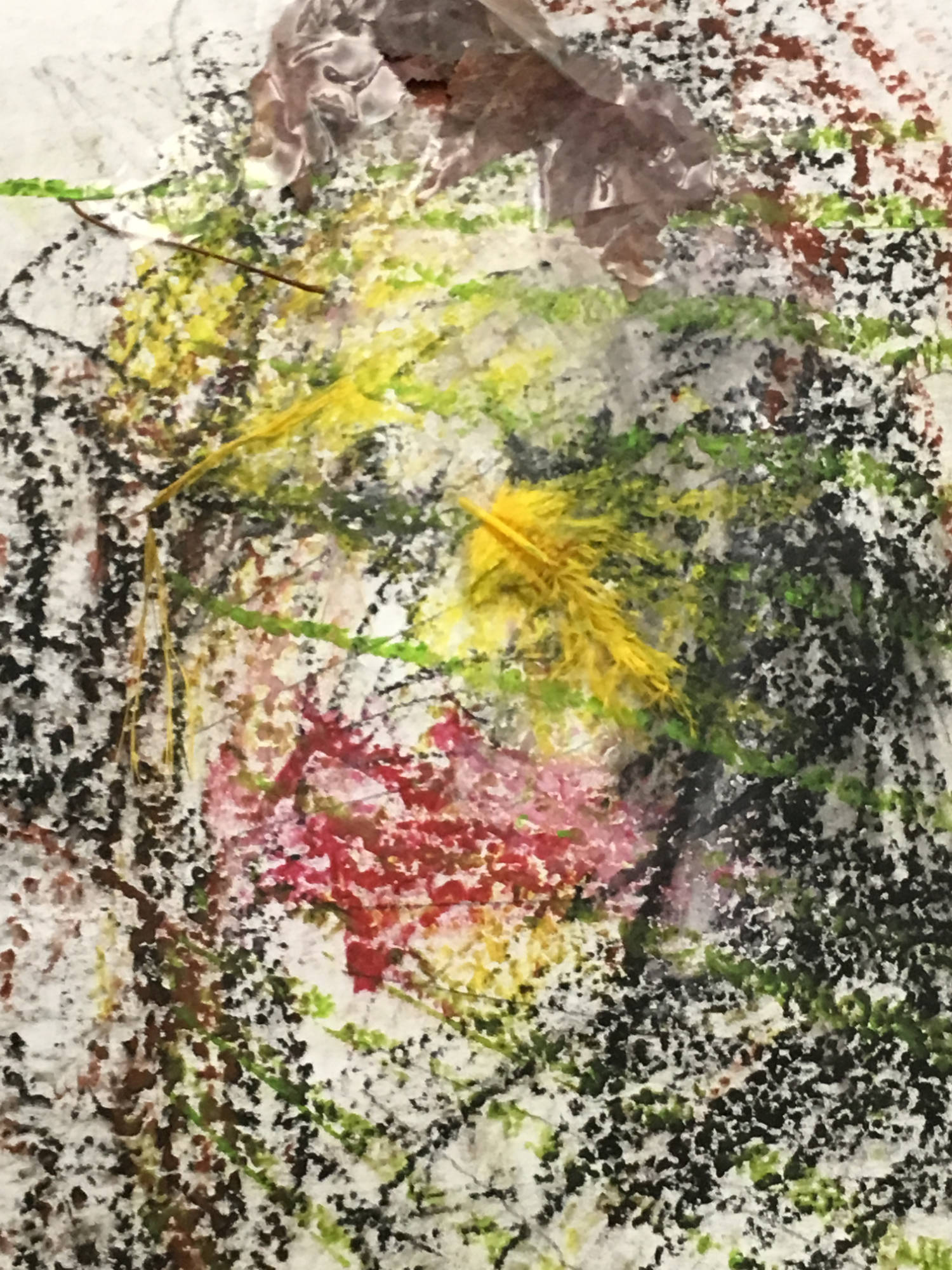

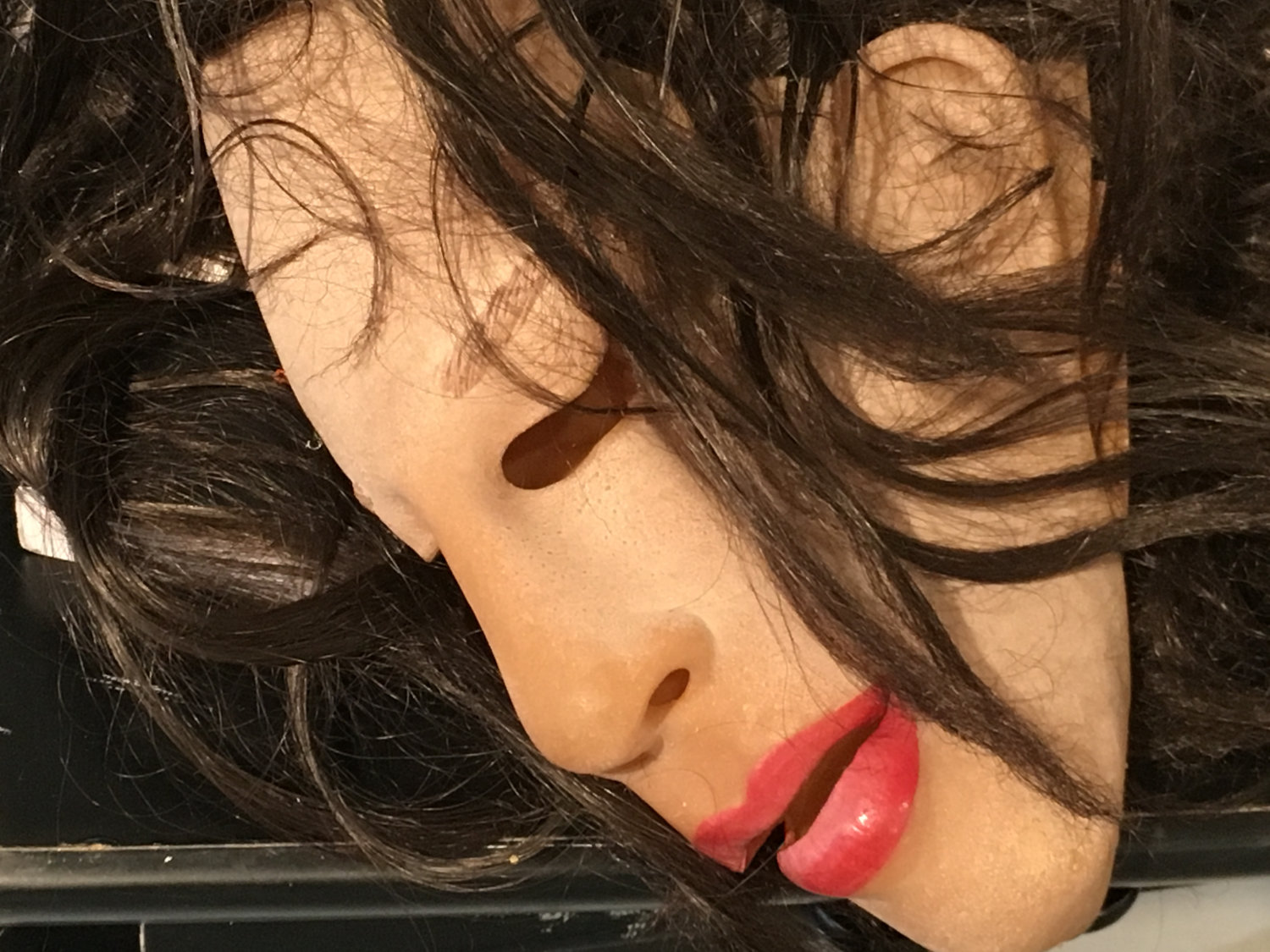

Lucy: What I do has to do with composition. Soon, we’ll go to the art store to get materials in which to construct, but for right now, we’re thinking about the page as found, a “screen,” or as one of the “moveable walls” in the art studio, Cheney. In another time, I’ll draw, but for now, I’ll wear a mask, and because you’ll be recording, I’ll lean my body between the camera and two walls, one in which I will be drawing on—the other, a wall on wheels, so it’ll be difficult, even for you, to render on the “page,” without feeling the tension between being seen and seeing what you are doing while never, static.

RVW: Dallas brought in the piece of grey-black fabric on the path that you passed, leading to the studio, and I realize the detritus was trash, and all you wanted to tack up were the tree leaves. I thought of gathering fallen sticks today along the road I run before the news of the applications. But a small, single piece of netting or fabric over the wall can do many things. In fact, it can create a means through which to think of all the natural landscape (say the burst of orange in the distance) against a precipice, found, or that which is left behind, a reminder: and that article on S.P., the shooter: all the excuses of a violent whiteness that goes unchecked, proliferates.

Lucy: The motive, of course, is anger, a simmering, just under the boiling point. Exclusion, or so is the reach. So, into the prose, and the collages—I think that’s what I was up to as I was interested in this notion—we were discussing, “white exceptionalism”—in that it must, somehow, always, through its need to both recognize and erase, clear a path, a history of excessive representation that stands its ground, specifically as desire, but that, in this fight, it enables seeing the capacity of a resistant self, however simultaneously masked or removed. An excellent route of killings becomes also an explosive realization: someone is there, and someone will always be his targets. It is not random. His anger, not the same as his animus.

RVW: I think what you’re getting at, in the question of white exceptionalism, has to do with infinite production of non-stop representation. That is, how many variations of you, Lucy, can there be in places like this, those discovered, created, and performed? By this, I mean, the world, in which you can pull your truck over in Peterborough, New Hampshire, for instance, the place where categories of stability have nothing to do with who you are when you, through me, I try to represent as a fluid mode: sentence, gesture, picture. See that PVC pipe over there? Black. This is what I mean. Seeing has to do with all the ways in which there is something impossible in your failure to stop noticing such objects in our site-line, as if there is no evil in Vanilla. That there is no assumed vocabulary for the racialized category of “whiteness,” is explicitly revealed in all this madness about this shooter who basically went fishbowl on our people. He is white and he is being ignored as being just that, and this might begin to suggest—there’s this sense that, finally, a secret is being revealed. In my estimation, it was deep in his DNA to go so live. I wonder who, for instance, shot up the churches in Tejas? More on that, though it’s not committed to my memory.

Lucy: What in the world does this have to do with me? Wait, let me answer that—I can’t be angry at that anger? That’s what it is—the motivation is that his ass never had to deal with the constant insecurity of just not being there, as in that he exists, just like that. It’s like, I want to get some money, now let me see how I can get it. Job. Hold up, let me get some exemplars here.

RVW: I’m already on it. Assumed, inherited, applied.

Lucy: Thank you, go for it, and then you have to attend to the prose, “Eyed, Virgil,” 1 or something like that, which will be crucial in teasing this out in another place. Maybe here, so don’t forget the substitutions: place instead of space. Time instead of space. The heart. The hospital floor. Me instead of character, or persona.

RVW: First of all, can you believe the headline? ‘I Wish I Could Tell You He Was a Miserable Bastard,’ 2 which I’ll get to later, because Virgil’s story, too, is calling in all of this rain, but there is something here that you need to get to, a couplet:

Perhaps his methodical and systematic mind had turned in a lethal and unpredictable direction. To the people who knew him, it is the only plausible explanation.

NYT on S.P.

There’s something powerful about the “methodical and the systematic,” especially as it is tied to the “lethal and unpredictable.” This is the thing—they are tied together in how one provides the route for the other, particularly in modes of representation, how the self is represented with such neutral innocence. The chatter on micro-aggressions is a bird song in this constant, and all the while, it’s disturbing, as though what’s plausible is the form that might be possible is in how you, Lucy, can take shape, or your mask off whenever you wish. You, in fact, are often only a mask. You dream of killing, maybe, but I don’t sense this is an actual possibility, for you.

Lucy: Are you thinking, in your stories, of Baldwin? For me, maybe, but only ever so slightly, I think, mostly of freedom, or rage fucking, and what that may promise. I know, it’s a very odd thing to go there, but it may say something about the ways in which I am exploring freedom. Simply put, I have no resources enough to act out in my aggressiveness in quite that way. I only once got close, and then a good spanking was enough to open up your eyes to what you did, however wrong, however intentional.

RVW: What do you mean? It feels like, in the end, there’s something that you have inside of you, something always brewing, a pointed resentment under the surface of every single exchange. You’re cultivating a language for resentment. In a sense, you must keep working in or against it, even at rest. In Peterborough, there was a pivotal moment in which some fellow eaters at Pearl looked at us, me, you, Zack, and Dallas, with such contempt. “All you got to do/ is walk on by,” sings THE AMERICAN ARTIST Michael Jackson, dead, in your head, but somehow, he translates…You give me butterflies. Maybe in this locus of freedom, something special happens. This was my rationale in taking photographs in the studio. My goal was to figure out a way to see the work in as many permutations through dance: the before, stretching, the after, compositions as sweat, and the during, the extension into shapes, bounce baby bounce. The remnants, as moves, exposed. We wanted to hold onto something, a record I could build upon, in whatever zone, release, trance. I wanted to draw the images, but in the end, I realize, I could simply shoot them, building the environment of our relationship with one another through the medium of the still. But yet, I leaned in on the possibility in drawing them, later, but the images will do.

Lucy: Perhaps this is it. Maybe this kind of all out white exceptionalism is tied to some slaughter-gene, the need to say, you’re wrong, and dirty, and weird, and you must be, ultimately, erased. All the time. The ejection of a presence as in I am a racist, so I think it’s tied to my people’s need to move people like you, out of the way for what? My inability to see you is tied to this need to destroy you—if you want to discuss any kind of plausibility in how I am thinking through exceptionalism, that is.

RVW: I lost my train of thought, because I was distracted, and felt, suddenly, like I needed to reach out to friends, and old mentors, almost rather impulsively. It feels really important to me, right now, as a way to work. What am I doing here at MacDowell, but thinking?

Lucy: Clearly, you are discovering…don’t forget about this, too, from Baldwin:

Bigger is Uncle Tom’s descendant, flesh of his flesh, so exactly the opposite a portrait that, when the books are placed together, it seems that the contemporary novelist and the dead New England woman are locked together in a deadly, timeless battle; the one uttering merciless exhortations, the other shouting curses. And, indeed, within this web of lust and fury, black and white can only thrust and counter-thrust, long for each other’s slow, exquisite death; death by torture, acid, knives and burning the thrust; the counter-thrust, the longing making heavier that cloud which binds and suffocates them both, so that they go down in that pit together.3

I created, today, a particularly broken dance via you, and you, maybe, seeing through me. The process was really powerful, because none of it felt, in any way dire. And upon second thought, what I read here as a binary, the living black body, and the dead New England white woman is something I missed the first time because I was not thinking of this in the context of the novel, or across two novels, as I was just, as always, stuck on race in the moment. To dance and to move down, and through the form of what explodes, and deconstructs, getting down is feeling, somehow, good, and in time. But it was/is precisely the contemporary novelist as a stand in, body as text, signifier and launching pad for these multiple literary figures that I feel extend beyond the writerly into what I am attempting to render each day in the studio, something I am hoping to solidify into a practice, forever.

RVW: What do you mean?

Lucy: I mean to say that, in my active estimation, Lucy in the Black Mask, today, was working out questions of rigor, so much so that the logics of representation were not “found,” as much as they were constructed, almost, accidently, through “what happened,” and how this was documented—but the thing is that you are constructing me, constructing you, or we are us interpreting Baldwin at MacDowell, the studio allowing for a means, for contesting static notions of who you think you are dealing with; for instance, the self as a stack of fabrics! Whimsy! We went outside today—Life!

Or the self as a means of seeing the self in pieces, the self on coat hooks. Here at MacDowell is, in part, where Baldwin wrote Giovanni’s Room. Oh yes, there’s that crazy depiction of that ratchet figure in the bar, where “It/Someone” floats, and deconstructs—

Now someone whom I had never seem before came out of the shadows toward me. It looked like a mummy or a zombie—this was the first, overwhelming impression—of something walking after it had been put to death. And it walked, really, like someone who might be sleepwalking or like those figures in slow motion one sometimes sees on the screen. It carried glass, it walked on its toes, the flat hips moved with a dead, horrifying lasciviousness. It seemed to make no sound; this was due to the roar of the bar, which was like the roaring of the sea, heard at night, from far away. It glittered in the dim light; the thin, black hair was violent with oil combed forward, hanging in the bangs; the eyes gleamed with mascara, the mouth raged with lipstick. The face was white and thoroughly bloodless with some kind of foundation cream; it stank of powder and a gardenia-like perfume. The shirt, open coquettishly to the navel, revealed a hairless chest and a silver crucifix; the shirt was co covered with round, paper thin wafers, red and green and orange and yellow and blue, which stormed in the light and made one feel that the mummy might, at any moment, disappear in flame. A red sash was around the waist, the clinging pants were a surprisingly somber get. He wore buckles on his shoes.4

RVW: It may have been one of the first books I completed when I became first interested in reading, but I don’t know if I recalled in any detail, this passage. It means a lot to me now, in the sense that it moves me into the sorts of constructions in how dance and costume provides a way of seeing through the moving body, and of being, a way of feeling, all the shrouds of clothes that fill and refill the body as it collapses into being, a series of covers, not masks? I realize that Baldwin’s descriptions, here, though, are so painterly, a figure too, that forms off of the page.

How to provide a sense of movement through the articulation of this kind of labor in watching the texts? T.V. head. Of making clear the connection between what is seen, and the modes through which vision is articulated? But the book still, after all those years, for me, acts as a resource. I wonder what it would have been like to read Giovanni’s Room in place of The Chosen, or G.R. next to T.C. as a child?

These are books that early on influenced my sensibility, in order:

Where the Red Fern Grows

Island of the Blue Dolphins

A Wrinkle in Time

Were these works filmic, or televisual?

Lucy: That’s a history that sounds more quotidian than moving, a history that you had with reading the book, maybe as a pre-teen? And now that you have a particular way of seeing, and reading, and living, you’re after something, which I, too, am interested in following. What you, at first, imagined as a set of sketches, serving as “backdrops” became something else, something more fluid in the drawing and painting… In some ways, the question of “performance,” too, became important in these new sketches. As someone performing in me, and drawing yourself, how are you getting at a lost lineage, or a broken one? How do the costumes, the dancing, and the work of recovery, allow a way back into necessary encounters? What is protected, and what is revealed?

RVW: Somehow, all of the stages collide, bump, and push against one another as you are dancing, dancing, even, with your hands. In some senses, it reminds me of the frequent use of the word, “permission” in our business. Like dreams don’t count? First of all, I hate that word, “permission,” particularly in how it relates to what might be produced otherwise, without it. That is: how do you enter the work without even thinking of such? This seems right—But Ok, does Kara Walker’s sketches give us permission to work on large pieces of ‘butcher’ paper? Nick Cave’s glittery spaces, the dangling spaces, how do they ask us to think of a way, in through the air?

Lucy: And for me, I want to ask—Do these strategies reveal freedom beyond permission?

I think they show a way, in, or they interact, as one might be in conversation with the work of being caught in a glut of feelings, signs, expectations. I am so happy that you waited to return to the dissertation, again, because so much of it was nascent in its completion; even though it was a powerful form, something to draw from. It was sent out in various performances, masks: poems, statements, notes, even in a way, through me.

The material was being used to enter stability, curiously enough, on the back of its own unstable content rendered into the ultimate short run book! 5 copies! One way to re-enter the work, again, is to reconfigure it across the looser forms that make up the connections, perhaps revealing a way back in through your “real” mask, or do you consider that to be your face?

Lucy: I am happy to stand in in any way that you need, even at rest. I am a victim of circumstance. I know you, for some great reason, were researching Black Racer Snakes. Do you want to talk about this instead, or in addition to where we are traveling?

RVW: Well, I’m not sure I know how to discuss it, but I do know that I was squeaking at squirrels on the sun porch of my studio. It was really moving, the sounds that I was able to construct, my attempt at reaching out to them, these little creatures in the distance. At some point, I was even dancing to the wind. One squirrel this morning just kept pausing, and then turning its head back to my silly human barks. I am not sure what I hoped to produce, but that’s the kind of relationship I was after. It was something that I found to illuminate, for a moment, that I was alone in the world with this animal, and then, all of a sudden, I heard these gunshots in the distance, something I hear with frequency here in New Hampshire. They were far off, and I wasn’t sure, any longer, of my longer plan to ask you to traipse around in the forest while I film you, navigating in the Hugo Boss Moto Boots you used to rock, for any of your heels would obviously sink in the soft soil of this place.

Lucy: Sure, I’m down, but only if you tell me about the snake.

RVW: Ok, truth be told, I looked up the snake because I was concerned with our safety. What’s around? I thought: What else can kill me? That is, I was not sure if anything might happen to you along the way, and long ago, when I was a young poet at Cave Canem, I crossed the path of a long snake, black, undulation across the road, thick, and fast. I yelled for my friend Ernesto Mercer, another poet who I thought would know something about the snake, because I felt that this was a visitation, and not a simple sighting. Ernesto wore pouches, filled with things I felt to be magic, and he would know, I felt. It seemed like he would, but I had no idea why, still don’t.

Lucy: How’s your friend giovanni singleton?

RVW: I miss her, and she’s at Cal teaching as the Holloway Lecturer for a year. I recall the same time when we met in the late 90’s, her working through a few things also at CC—giovanni was always in the computer room, constructing concrete poems in a magic bubble all of her own. Not sure why you asked?

Lucy: I am thinking of her gun/camera poems, “DON’T SHOOT,” which is so beautifully loaded. Two “guns” on a page face one another, but not quite, one lower than the other. Two shapes. One is a pistol, the other is a “vintage” camera that echoes the shape of a gun, both illustrations tip to tip, head to head. I overheard you talking about the circus today, how it’s gone to the past, the carnival, but we have a total Clown in the White House, Bozo Hair, an evil drag queen clown that everyone is fascinated by, until we go headfirst into the canon, and we say, how did this happen, as we perish yo!

RVW: It isn’t my concern. Well, mostly, not, that is.

Lucy: I think that what you might be up to is really curious, because the work you are making has no audience, at least when you are making it. It feels like it is only us. Is there a difference between the studio and the desk, the page, and the body? Perhaps the studio is without an audience, just “studies” in the studio, or something like this, poses that you recount, and begin to project and draw. And then you move. I guess you have to figure out how to do this in the spirit of the draft, one force following the other. It was clear that when Jo, the photographer, came in, there was some energy in the room of which you were unaware, but I don’t know what the photos look like that may have captured some of this. In a sense, I was interested in the ways that she was drawn to the forms I was making, and how this made you think through being looked at, and there was that moment when you began to weep inside of me. Do you remember? It was before Jo called what you were doing, “hot.”

RVW: I recall when I was talking about making shapes. Shapes would equal the language, the mark of being able to communicate something that made less sense in an accessible language. I was interested in how this helped me to move outside of perception, at least in terms of letters. This is to say, I was hoping that I could communicate what I wanted to make, and how I might manage to make the work connect in something filled with more tension. Maybe it was as simple as trying to feel something through the texture of the body, or in the material you pose in your being as I am trying to remember something in mine. I wonder about how this might make a difference, that is to treat the book, itself, as a static object, yes, but its photos and its insides, as a way of thinking through the work, and a form through which to enact it.

Lucy: Or feeling through it….

Lucy: So, for at least two nights, I have been cradled in a black mask, inverted, and my hair is flowing outwards. What do you think of that?

RVW: Of course, it’s intentional, mainly because your hair pours out, making an extended small gush into the studio, and the juxtaposition makes a way into the space between you and you, we and we. You are a night light! And we passed the gazebo every day, and when we entered it, you actually heard what was going on outside!

Lucy: You’re funny, and you’ve yet to answer my question, to be reliable in the way that you can be, because maybe in your attempts to think through the question of time has more to do with space than what it means to wait.

RVW: Are you asking me about James Baldwin?—Maybe in his relationship to the sentence? Clearly, there has to be some form of remedy as analysis, or an analysis that combines the relationship between the multiple configurations of that which you are clearly a part. I think following Baldwin, here, might unground any actual analysis:

If, as I believe, no American Negro exists who does not have his private Bigger Thomas living in the skull, then what most significantly fails to be illuminated here is the paradoxical adjustment which is perpetually made, the Negro being compelled to accept the fact that this dark and dangerous and unloved stranger is part of himself forever.5

I point Baldwin out, here, because this serves as a means through which to think about the relationship between what we are, and how we are portrayed. The skull, mind and mind, the layering of the self in the head? Unloved stranger.

I want to say something about the mask as a form, surrounded by the self, a forced vestige, or the only route back through the self, a way of seeing a way back to reality. The thing about silicon is that it does not breathe.

Lucy: Say more.

RVW: I don’t control you, of course, because when you are around my skull, it gets very hot, so I can only function as “myself” for a little while until the saliva or the spit becomes too much. When you are around me, I feel this heat, and it is something really transformative in that I cannot see, really, can’t speak that well, and if I do, I then become, clear in my hostility, and maybe my resentment? The first masks that I used were cheap, and they eventually fell apart, the plastic becoming a hazard. It’s as though, what you produce in me is a kind of way to “fade” myself from one mode of identity into the next, so that the actual self that you are is only somewhat related to the person, or the people, that we are presenting. Silicone, then, is a common denominator. It’s like starting to the see the shape and the form through continuing to render away.

Lucy: But how does this relate to my hair, which is synthetic, and you, who are returning to earth, head ablaze, and coming in hot, all the time? In all the fabrics, and all of the surfaces that you are working through, and “rendering”—it isn’t random, but what you are learning, in way from the writing, is a language, in fact, that is more familiar.

RVW: I think that one way to think of it is that the very manifestation of race, something that occurs to you, all of the time, because you are unreal, and that the terms change when you mate the material of the self, and then turn it inside out against my face. To reveal what you may ask? Leaving a space for one figure to make room for another. There is no logic that exists between us, and the thread will continue to reveal no connection, just a direction, which I feel is the practice you are after in locating a body that is not recognizable, but is somehow, animating you toward me, and the vector, not the line! There’s an essay I would like to look at, closely, which really gets at the edges of Kara Walker’s work, called, “Kara’s Dust,” 6 which centers on the traces of Walker’s work by focusing on the charcoal left behind at the base of the drawings, “pooled,” on the floor. I am really interested in that, particularly because you left pieces of eraser, and glue behind, tiny deposits, too!

Lucy: And I wasn’t there, at the Walker exhibit, but you were paying attention to the “skirts” of Walker’s work, the ways you were thinking of the lower edges of her drawings, the paper and what extended there, before the catalogue. I would have made you think very consciously of yourself, had you been more alert and on the ready to accept the work while wearing me, but you were afraid. It feels like you are, in a sense, reflecting on what happens below you, or at the under-periphery too, in these photos. I get it, had I been there, over your head, in my mask, I would have clearly been under assault, or taken up too much space. You could not have created, effectively. It worked at the Nick Cave exhibit, but I am unsure if it would be possible in another space, especially in the city that red hot day.

Eyed, Virgil

“This is a most serious matter,” is what Virgil is thinking, the dream so frightening because it asks him to flee from his relaxed state, one in which he is only listening, and not reading, but is moved, still, by WispBlondeForearmHair who taps Virgil on the shoulder to let Virgil know it’s Virgil’s turn to go to the bathroom at the front of the plane.

WispBlondeForearmHair’s Kindle and natural Sperry’s on the Southwest flight only slightly move Virgil before this, but not so much movement where his feelings have left him wanting something more, because he left this behind, Virgil thinks, in the City-of-Smoke, where he was compelled by the state of his own continuously changing state.

When BigWhiteSunkEyes sees him in the café, he tells Virgil that he might do something, “maybe something great one day,” but Virgil can’t figure out why this total stranger might imagine what Virgil may become in the future, but Virgil and BigWhiteSunkEyes are thinking, however directly or indirectly, about fame. But Virgil is already famous. He sells books. He teaches. He travels. He performs. He receives calls to do all of these things a good amount of the time, and of course, his honoraria increases at a similar rate to his need for 4 to 5 star hotels.

He eats well. He looks at books and cruises on and off line. He has Butch. He is letting Clean go to a new place in his heart; however, Stream helps him access a past that Virgil is only now seeing in disparate parts, flat dreams, steel girders that he’s willing to assemble either on drives, or while still. Virgil hangs his masks on the hooks in the studio, and on the upper ledges of the moveable wall to begin to register his movements between subjectivities, but mostly to give him some means to mark the relationship between his material, his practice, and his body.

He is thinking, of course, of Nick Cave, and the fact that Cave is an actual dancer, while Virgil is only a visitor to this (and other forms), but in each, save poetry and cultural criticism, Virgil’s training is mostly peripheral. Virgil notes how Cave, especially, in his largescale exhibit Until, fills spaces between the floor and ceiling, like Kara Walker did in the Domino Sugar Factory in the BK. Our Past, Virgil thinks, which is a constraint, black jockeys (Cave) or black torsos (Walker), each loaded on top of another.

As Lucy, Virgil was pushing the moveable wall backwards. They misestimated their sense of leverage, placing too much pressure, high, not even thinking about the balance point. The wall crashed backwards, hitting one of the permanent ones that would hold, soon, Virgil’s drawings. It left a small yellow pock, bruising the cheek of YELL-O Face, the painted rubber marking the white studio walls, but just like he does to the tubs and the toilets after most every use, Virgil rubbed the evidence away.

But here was the issue—the heat wouldn’t cut off in the studio. It blasted and blared after the wall hit the floor, the crashing of it, still reverberating in Virgil’s body, sometime after it stunned the floor. Did I destroy the heating system? Would Virgil be to blame for destroying Cheney, the studio’s ground structure ruined while he wasn’t even dancing, his lost girl back step on Lucy’s camel suede, tasseled heels, their leverage against the wall creating a falling that was both an accident, and something he captured in the iPad Pro’s gaping frame?

Virgil thinks, I look so dumb and surprised.

Others artists have died, Virgil thinks, too early, because they did not enjoy their lives in ways Virgil constitutes his freedoms, risking masks in cathedrals, streets, in classes, or alone, their blind, pushing over walls into who knows? Could this ever happen to him?—Virgil will never forget when June Jordan stood behind the lectern. For Virgil, the lectern is a prop, often one that’s set on its side, or needed to be ridden like Virgil wanted the Thai Lady Boy to ride that White Beaver Dad, but this did not happen in that particular porn.

The White Beaver Dad did some pumping in the slick hole but it wasn’t violent; it was stiff, and still, but that passive act made Virgil cum, for sure. And once, during the Polite JO. Or, in the two smiles, and then during the close of the scene, before the camera went off when White Beaver Dad stopped the recording, Virgil thinks of what stood in the way between him and what Virgil wants.

For June Jordan, the lectern was a shield: You would not talk to your White Professors this way! But still, June Jordan was often flanked with whites who probably thought they could talk to her however they liked. Where did they go with June Jordan, and what did they edit of hers, and how did they call her name, and, really, how were those Whites, who Virgil was near, but whose roles he would never, completely understand? Virgil did not, because he was young, beautiful, tighter, ever leaving Virgil with some innocent ideas of his own.

Virgil’s voice was then being formed, his seeing what he understood, then, to be the “podium,” as a mode through which to activate one’s safety, a raft, a defense. For Virgil this was imperative, in the sense, that it allowed him to see an escape route, no matter how minor. But the thing is, June Jordan was taking one for the team. Perhaps, it was an important thing to do, to take one for the team, but Virgil, who is cold to his fingers, while writing on the porch, is unable to accept the reality of the cold being the sign of any future failure to one day understand why, but he’s getting close.

Oh yeah, Virgil will soon propel from New Hampshire to California, a California that is on fire, and burning while Virgil is cozy in a cool room overlooking curled, red-punch looking leaves. June fought. So Virgil is invested in prose, and there was a time when he thought of “the prosaics” as something that existed in the field of his desire, despite the fact that he hadn’t executed a form of prose he wished to create, yet. But still, Virgil has a body. And he has a body of work. He understands his calling:

“Jasmine Peals Re-steep!” “Is this for you Bud?”

Virgil sits at the brown, broad table to recalibrate from all of the times he was patted, and tapped, but Virgil, unlike some of the writers, like June Jordan, who died, he feels, of course, way too early, does not feel some kind of way, about this tapping, because he, after all, is a flirt. Virgil holds no resentment towards the “touchers,” but, no matter what, he will not forgive the “touchers” on GP. Those stink bugs can come waddling along on their little feet, and still, there will be no escape from the life that they think that they want, all up in their intrusions. Virgil is not a waiter. His laptop is not a menu. Virgil’s iPhone is not sanitary. Its “flashlight,” also will not reveal the lost 100K earring in The Big 4, which belongs to PrettyWhiteOldLady, who is not the arbiter of what’s interesting to Virgil, and she’s right—Virgil is sweet.

The contracts are so set, like James Baldwin reminds Virgil—they form a cage, and there is, ultimately, no transcendence, but there is always tension knows Virgil, the play between characters, memories, figures, even the slightest dreams, those that flash next to one another, forming relational ideas, so that the form of prose, for Virgil, emerges out of chaos, working in such a way to create thinking that ricochets between subjects and time, or maybe even, simply, in time!

In other words, Virgil’s escape between his life and his dreams is the price of fame, that there is a space when the signing of a book becomes the space for making live art, say a drawing as a union between symbols, multiple, and however available. There is no tie, nor anchor. Simile. Simulacrum. Only line—

It doesn’t matter to be so stuck in the dense field of prose Virgil thinks, because Virgil cut his teeth in New York with Jennifer Jazz The Famous Artist. This was at a time, in a basement reading, where Virgil learned to understand the reality of producing what matters, intuiting and remaining as paired down as possible. But what Jennifer Jazz The Famous Artist taught Virgil was that he could, at any moment, like her, come in with a giant binder, yell back at the heckler, in the corner of the bar and drill out to the street without reading at all: FUCK YOU STEVE!!!

Before he is rushed out into the street, Virgil wants to grapple with this dream:

Butch is brown, maybe South Asian, and waiting for him at the movies, and then leaves the movies, and WalrusStache is kissing everyone in the same room before he leaves for a birthday celebration to which Virgil and Butch are invited. But the invitation is made up of a long dream of steel girders, and walkways Virgil can see while he’s submerged below them. Clean is in the dream, and in the dream, he promises Virgil that he will take him to a mansion, and Virgil understands that the mansion exists. And though Virgil does not imagine the mansion, that is, what it might be like inside, or is for real, he does develop a sense of it from the long summer grasses that brush his legs as they walk with one another. There isn’t a home that either of them head towards. Something else is moving them, propelling them forward together into a world of privacy, of seconds, of a shadow toggling against a wall. Virgil is so quickly ready to lie, to say he may not go, not because he would not want to actually meet with any friends, but because he could blame the calendar for the mistake, the mistake of Butch not letting Virgil know about their dinner date with their friends. In the end, Virgil will not go with Clean, but instead, goes searching for Butch, who is suddenly South Asian and waiting in a classroom that is a movie theater, too, a movie he faithfully left to find Virgil. How Sweet! Still!

The search, and the waiting—the buying—it all feels like a flood that Virgil cannot contain, his body feeding between emotion and structure, say sadness and rusted white steel plates linking Virgil’s body with his vision. The vectors that Virgil are after move between lines of feeling, and extend into space; they bleed outside of the bags, dripping fat and blood-grease from the podium he leaves around the lectern’s base.

There’s still fat in the bags, fat cut from chicken, fat cut from the meat when it was still frozen. The trimmings inside the bag soften under the stage lights. Virgil hears someone say “gross,” or at least Virgil wants to hear this said, and he looks around the audience, haunting the crowd while pacing around the aisles, scanning the room, gazing at the spectacle of what was about to happen, as in what he was going to make in that space, something only Virgil knows because the position of his body is still, and silent, yet something moves around the tip of the stage, as if plunged between forms, or seeping in the vestibule where someone like Virgil, but not Lucy, is shot.

Virgil has created an eddy in which to find his relationship to how to love, mostly, and on top of that, there is another diagnosis, something that draws him in to seek more ways of understanding the dimensions of what he wants to get at through an opacity in which he is just learning to render. What’s under the work, Virgil feels, is not quiet, but a flow, not anything that Virgil can control, but something else, a constant seizing of the self as it erupts out of what is both not quiet and in the morning rain. What would have happened if Virgil had a baby that was his own, say his only child, behind that crashing wall? What if it, or even “he” were struck by that moveable wall falling in the studio that morning in which Lucy was only starting to dance?

Virgil ponders, looking out at the field into a burst of wet-red in the gulf of trees, and the fallen gap of evergreens. There is no sound, but a fallen pine cone appears where Virgil registers, brown. Virgil, who is more interested in RedBeardGatter aka SP, who mowed down those Country Whites and Others for sport, did not predict the fires in California wine country, embers soaring into trees, houses, cars, vines, even in flat Fairfield, but he did understand the relationship between the fires, and the distant hunting shots that he would hear, and the dead, these somehow the demands of those wanting silencers still for sale to augment the assault weapons doubling by the record buys.

Vanilla.

Gambler.

Quiet.

Mystery.

In his view, Virgil hears the kinds of gunshots that he has never heard in nature, but thinks of how they echo so familiarly, and knows that even with access to the orange hunting vests, he will not walk through the deep woods, but instead, will run along the trail to sense what’s trying to kill him inside, a dread that his DADWHOKNEW and MOMWHOSPIT buttressed against him, a greater power than freedom, they instilled, was how he needed and learns to continue to see far ahead, and even still, into his imagination. Life source, Architecture: Capacious.

Your bullets are a sign, Virgil thinks, which could be a line in a song, or a dance move, or a way of thinking, a forced thought through the rain pounding down on the pressure it takes to write, and maybe, to heal. From looking? From listening? Virgil’s father, SadNowWaitingtoHeal, amidst the gun shots, understands this too—Dementia as A.W.O.L. for several years, his mind has become a retreat, captivity, a cage of lasting imprint, the body bound by fever, but a body still, never intersectional, a dull word, only cuts.

“For real…and off the hook” Pockedwhite describes the cookie in the case as such, which Virgil will not order. But he likes to think of eating the cookie as an option. The space of the wish to eat what he won’t, at least not then, is caught in the site of the little brown boy, directly in front of Virgil, mouthing the edges of the Corten Steel refrigerator case at Verve. The Brown Dad notices his little brown boy after the fact of his mouthing the edge of the metal cooling ledge, and against this, he notices the slight change in temperature outside of the case and in Virgil’s body, maybe warmer, which of course, is tied to a more parched memory, the transitions between building his relationship to the self and how it’s marked by temperature and thought. There is simply no home, or place to where Virgil can return. Sigh. So, this little place, where the little brown boy’s mouth butterfly licks the steel is where it’s at!

Or color: Slits in army green sweats reveal leggings, and these leggings point to natural Birkenstocks. In the echo, “Do you know what I mean?” Or “So good”—the space of the fictive relationship between the body, and the body’s relationship to what’s encrypted accretes in the mind—perhaps this is the writing, the choice in not dancing for a while, to check back in, in language.

BigLoveBrilliant illuminates this by providing a single gesture, the bodies attuned to the space between what is known, and that which can be constructed in what might be. Virgil must continue, he thinks, to get better, to never stop being hungry, to be fed, to desire the next point of consumption, to be altered in thinking how to not feel full.

“Try this, it’s really good.”—

All Virgil wants is to build his life in a panoramic relationship to his surroundings, to fly into what he hears, and to move in the feeling of a periscopic conveyance. Of every consequence, Virgil has a need to see, not to not quite “peer around corners,” in the way how this vision was once described by one of his “teachers,” but also how it is broken, as one can see into the truth of a lie, I have a wide spread!

In the office, the BlackGiant says “From Hell,” when Virgil asks where the mailings are from, the feeling of the rage is configured in BlackGiant’s stance, seeing inside of the circumstance of our particular condition, Virgil thinks.

“Yeah.” “We’re like in the middle of nowhere.”—

“What are those??!?!”

In the edge of knowing, a black body is abducted. A fat pink black girl, who has allegedly stolen, is choked to almost death as link to one who was killed, shot in the midst of the perceived crime. The perception is the landscape that is rendered active, and in retrospect all Virgil hears is tearing in a grove that is not “ticky,” a squirrel darting and a blue and brown lunch bag, and geez, are these things free?

BrownThick waddles in too, with Birkenstocks, hide brown, just like Virgil owns, and in this shared ownership, Virgil feels remorse that his body is not long. The gutting of the world as he knows it produces a set of sores in his brain from which he will never recover, or maybe he will learn to advance in this, as ever, in oh, the pulse, and the sway of an emergence in a Black Walk, peering out, to say, is that you, there?

↩

2 Tavernise, Sabrina, Kovaleski, Serge F., and Turkewitz, Julie. “I Wish I Could Tell You He Was a Miserable Bastard,” New York Times. October 8, 2017: (Front Cover). ↩

3 Baldwin, James. “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” Notes of a Native Son. Collected Essays. The Library of America, 1998. (c.1949), 18. ↩

4 Baldwin, James. Giovanni’s Room. (New York: Dial Press, 1956), 59. ↩

5 Baldwin, James. “Many Thousands Gone,” Notes of a Native Son. Collected Essays. The Library of America, 1998. (c.1949), 32. ↩

6 Lansdowne, John. “Kara’s Dust,” The Ecstasy of St. Kara: Kara Walker, New Work. Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 2016. 30-33. ↩

Ronaldo V. Wilson, PhD, is the author of Narrative of the Life of the Brown Boy and the White Man (University of Pittsburgh, 2008), winner of the 2007 Cave Canem Prize; Poems of the Black Object (Futurepoem Books, 2009), winner of the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry and the Asian American Literary Award in Poetry in 2010. His latest books are Farther Traveler: Poetry, Prose, Other (Counterpath Press, 2015), finalist for a Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry, and Lucy 72 (1913 Press, 2018). Co-founder of the Black Took Collective, Wilson is also a mixed media artist, dancer, and performer. He has performed in multiple venues, including the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, UC Riverside’s Artsblock, Georgetown’s Lannan Center, Dixon Place, the Atlantic Center for the Arts, and Lousiana State University’s Digital Media Center Theater. The recipient of fellowships from Cave Canem, the Djerassi Resident Artists Program, the Ford Foundation, Kundiman, MacDowell, the National Research Council, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, the Center for Art and Thought, and Yaddo, Wilson is Associate Professor of Creative Writing and Literature at UC Santa Cruz, serving on the core faculty of the Creative Critical PhD Program, and co-directing the Creative Writing Program.