“It feels like my working practice is a form of listening to the voices in my head and it’s as if I mishear it when a poem doesn’t work—I haven’t focused enough and heard it. It’s like listening really hard to silence.”

“I’ve always been very against flowing rhythms, like particularly against the iambic pentameter, the main rhythm English poetry has worked in.”

“My kind of model/structure, was always kind of the Japanese Noh play, …it’s really interesting, that thing where you have a conversation going on between people and then a god or something-from-the-other-world…appears. And to me, it works like that and you have this kind of rational, kindling dialogue and something that summons something that is not the poem but detects a poem. I am interested in the kind of poem that shivers when something from outside comes in that you are not in control of…. It’s like a tidiness summoning a messiness.” –Alice Oswald, from a dawn springtime walk by the River Dart with John Drever

*

Like the seal in Elizabeth Bishop’s poem, “At the Fishhouses,” Alice Oswald is a believer in “total immersion.” Readers may know of her love of “wild swimming” (as the English call swimming in natural bodies of water—rivers, lakes, oceans, etc.), and how she charted the River Dart in a book-length poem of the same name. This image of a swimmer can serve as a metaphor for Oswald’s spiritual and generative technique: as a body moves inside and through the liquid element water, the mind rides above the waterline, absorbing and projecting sensate-driven thoughts onto an empty landscape—the page. Such deep-diving is evident in all her poems, be they about stone walls, wildflowers, weeds, or as, in her latest book, Nobody, the ocean. In Oswald’s hands, the pathetic fallacy is not really a fallacy as she sounds out the consciousness of our planet: flowers feel, the river speaks, and the ocean ruminates, struggles, converges, mutters, and murders.

In equestrian terms, Oswald practices a controlled—but deeply imaginative—equitation, a kind of dressage with words—man and horse fused—though in this riding ring, the horses are of water, earth, air, and fire. If pressed to define her, Oswald might be called a visionary landscape poet. And has a poet ever had a better education to become a poet? Living in curated gardens shaped by her landscape gardener mother, Lady Mary Keen, Oswald first studied horticulture, and then went on to study our mortal myths in the Classics Department at Oxford. Oswald now serves as Professor of Poetry at Oxford, the first woman (incredibly) to hold that position in over 300 years. Her lectures have been made available online (another first for Oxford), and each offers rich and thrilling listening. The lectures are peppered with references to the work of other artists, both historical and contemporary, offering insight into how Oswald thinks about the most elemental aspects of poetry. Oswald comes from poetry, and her poems describe the places and phenomena that remain mysterious to our technologically advanced but declining civilization. She makes no Doomsday arguments about the world she records and dreams through, though her realm is dying; we know this to be true. One longs to be drowned in her work, which is of and about the material of the world, but moreover, the realms beyond it.

Oswald is a contemporary Modernist. T. S. Eliot suggested that poetry should be as well-written as good prose, and when reading Oswald I am reminded of prose writers like Henry Green and Anthony Powell, as well as Beckett, who she is often compared to. To the list of poets she is usually compared with—Hughes, Eliot, Heaney—I’ll add the influence (or reverberation) of David Jones, the Welsh Modernist, not David Jones aka David Bowie, though one imagines Oswald would sympathize with Bowie’s iterative public nature, as well as his rock-solid commitment to his art.

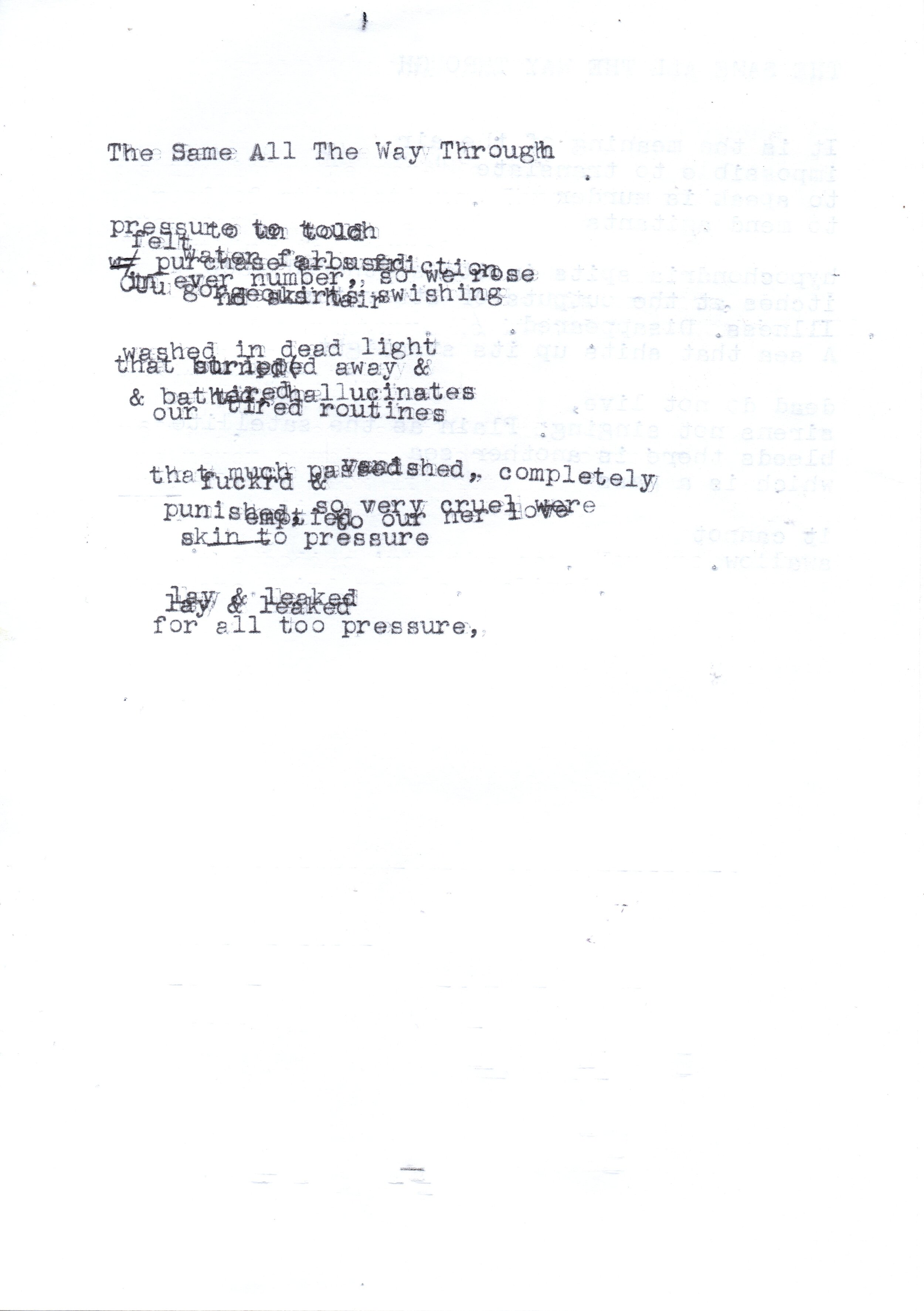

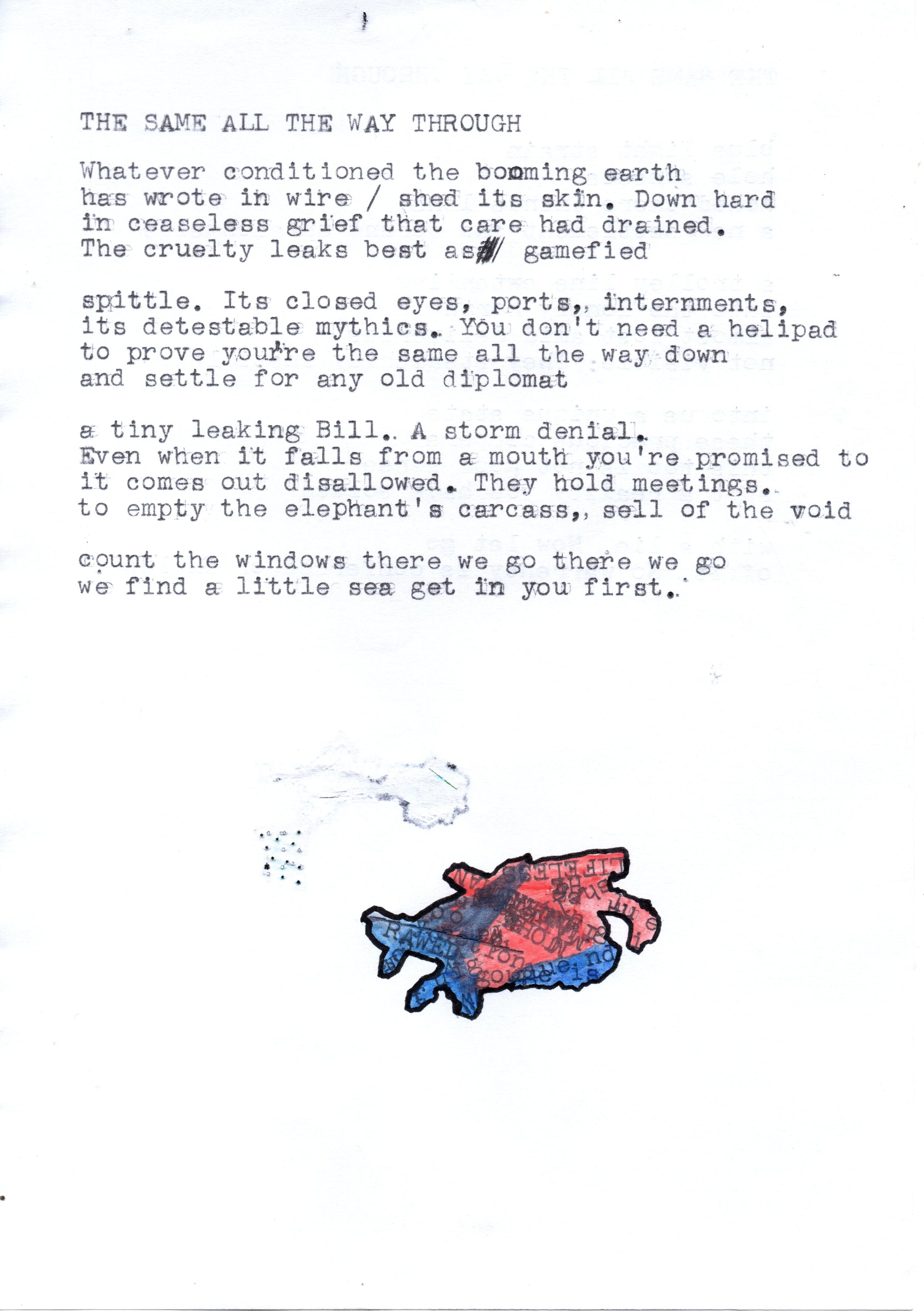

Oswald is a public poet who believes in performance, and she brings that ancient aspect of poetry back to her modern audiences. Her readings are not passive mic-drones, and the tribes before her receive what feels like ancient wisdom from her stylized and pressurized delivery. She often collaborates, or rather, enacts exchanges between her work and others—and several of those collaborators appear in this issue—Sarah Simbet, Maribel Mas, John Drever, and William Tillyer. As with Dart, Oswald often performs research and field work for her poems to deepen the work, not to avoid it. Her research screws her further into her subjects, testing her mastery of description, oration, imagination and meaning-making. In addition to collaboration and public performances, paper ephemera artifacts (see https://www.theletterpress.org/) are also part of Oswald’s poetics. But, while Oswald is very much in and of the world, she retains the deep, exquisite focus of an Emily Dickinson, who shut the world out to triumph over it.

Fifty fine critics, poets, and artists from the United Kingdom, Jamaica, and America came together to consider Oswald’s language, images, and her importance to contemporary poetry. I truly wish I could delineate what I find special (and Oswaldian) in each entry here, from the American poet Emily Wilson’s botanical drawing of an Iowa Bloodroot plant to English poet Peter Larkin’s crackling (and cracking) poem about trees. American poet Carl Phillips’s poem calls up “a paleolithic fragment of a reindeer antler decorated/with an image of a horse,” while Jamaican poet Ishion Hutchinson writes in the titular poem to his newly reissued collection Far District, “the sea is our genesis and the horizon, exodus.” Christina Davis’s poem about Walden Pond calls up a “sacred” American landscape and place, as does the feltwork of English artist Antje Derks, made from fallen Dartmoor wool and naturally dyed with its vegetation (and some from her garden). Do not miss English sound-artist John Drever’s recording of him and Oswald walking by the Dart River, a well-trodden walk for her, and integral to her process in writing Memorial and memorizing it for performance. The poetic work of English poets Harriet Tarlo and Kym Martindale summons up Oswaldian terrain, as does Adam Piette’s brilliant meditation on “sound” in her book Woods, etc. American poet/editor/critic Donald Revell reviews English poet Toby Martinez de las Rivas while delivering a master class on pastoralism, as Englishman Tom Phillips situates Oswald in the English poetic landscape of the last fifty years. English poet Tom Pickard’s photographs of dramatic Cumbrian skies speak to American poet and translator John Tipton’s dark and dreamy translations of four Dionysian prayers. English artist Sarah Simblet’s fascinating water drawings work in beautiful juxtaposition with William Tillyer’s watercolors, where the medium functions more as water than pigment. American poet Tom Thompson explores Maribal Mas’s mechanical drawings that accompany a letterpress edition of a selection of Oswald’s poems called A Short Story of Falling, while American poet/scholar/critic Han VanderHart mediates on Oswald’s “radical spirit and imagination,” reminding us that poetry comes from a “thwartwise” approach to the world.

There is more: Poetry by poets Andrew Motion, Komo Ananda, Gabrielle Bates, Amy Beeder, Kitty Donnelly, Asha Futterman, Tjaden Loito, Katie Peterson, Randall Potts, Kerry Priest, Verity Spot, Cort Day, Mandy Gutmann-Gonzales, Geoffrey Nutter, Nigel Wheale, Martin Corless-Smith, Suzannah Evans, Geraldine Monk, Twila Newley, Abigail Parry, Jack Thatcher, and Joshua Weiner. Essays by Miranda Field, Giles Goodland, Martin Corless-Smith, Catherine Theis, Joyelle McSweeny, and Joshua Weiner. Reviews by Ian Brinton and Mary Newell. And finally, Artwork by Elisa Jensen, t.pleman, Katrina Roberts, Cal Wenby, Marcus Good, and Carolina Ebeid. Truly, each artifact here is special, and I hope together the issue makes one hungry to know more about this great living poet, as well as the elements of our world: water, sound, land, sky—and language.

As Oswald says, “I’m trying to spend my time interpreting noise into language.”

I need to thank Martin Corless-Smith especially for his generosity and enthusiasm concerning the issue; in fact, he should really be listed as a co-editor. Thank you to Anthony Robinson for his crucial editorial help. And Kathyrn McKenzie did the Lord’s work getting everything in order after I created a cyclone; she deserves all the good things that will come to her.

Finally, I tell my poetry students to go “underwater” when they write, which is shorthand for “write from a place that is not exactly consciousness—find the poetry down there, not in your cerebral cortex.” Oswald is writing the poetry I have been missing for about two decades; you may have been missing it, too. If you have not yet read her work, start now. She will help you live more deeply.

-Regan Good

Guest Editor