My Father’s Work

Part One: The Trouble I’ve Seen: My Father’s Personal Record of Public Events

History

A memory from the ‘70s: I am walking through the little woods between our house and the bus stop on Mallard Lane in Westport, Connecticut. I am about seven. My father is a freelance writer and reporter, and he is home when I return from school, not my mother. It is Indian summer, and as I walk through the woods, I hear a voice booming through the trees, as if coming from a loudspeaker. It makes my heart pound. The voice is melodious, deep, rich, full of gravitas and import. By the time I reach the edge of the woods, I can see my father at the picnic table at his typewriter. As is usual on warm days, he has strung an electrical cord through the kitchen window and he sits in front of a giant IBM Selectric and his junky Radio Shack tape recorder. Martin Luther King Jr.’s voice is broadcasting across our lawn. By the time I reach my father, I see that he is crying.

Growing up in Fairfield County, I heard the strange names of southern towns, like Notasulga, Hattiesburg, Tuscaloosa, Selma, Tuskegee—places with mysterious, American Indian sounding names, so different from our East Coast colonial nomenclature. My father’s verbal renditions of his journalistic work at bedtime left a nervous child sometimes paralyzed with fear. He told me of dangerous moments in his career, and for years I waited for these men to come for him. I imagined the Klan in robes on horseback riding down our gravel driveway. He told me about the Klan, how they lit crosses soaked in gasoline on black people’s lawns, hung men in front of their families, and terrorized black citizenry across the South. He told me of the Southern sheriffs who unleashed barking dogs on people marching peacefully for their rights as human beings. He told me of cars full of jeering white men carrying bats and chains; he told me of their cruelty and their radioactive hate. Though we were white and safe in a Connecticut suburb, the violence my father had seen affected him, and it seeped into the fabric of our lives, as it did the nation’s. His experience shaped my older brother, Sean, and me in ways one day I might be able to articulate: a brokenhearted father is a hard row to hoe.

For the last few years, I have been on an extended electronic Easter Egg hunt: I look for photographs online of my father, Paul Joseph Good Jr., reporting during the Civil Rights Movement. I scan photos of marches looking for him; I pour over the black faces and the white faces, the women in kerchiefs, the men in overalls, and the solemn, serious children. I look for him in the background of pictures of black men being beaten by white sheriffs, along the side of highways, on bridges and on sidewalks. I look for him in pictures of news conferences, sit-ins, swim-ins, dive-ins, gas stations, lunch counter protests, and courthouse steps. I look for him in photos of KKK meetings where their white satin hoods resemble satiny dunce caps or floppy Pope’s miters. I look for him and I find him, mostly in black and white photographs, which is fitting, but sometimes in living color, which is startling and sometimes makes me gasp. I am so good at this Paul Good-finding game that I can recognize his elbow, for example, or 1/8th of his nose, or a partial glimpse of his distinctive hairline.

Here he is on Edmund Pettus Bridge writing on a notepad, the crush of the march behind him and his photographer, a National Guardsman high stepping it to their left. I love this photo, mostly for the men in the front wearing sharecropper overalls in solidarity with black farmers. (The Associated Press)

Here he is holding the mic boom at the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine as motel owner Jimmy Brock hysterically runs around the outdoor pool, pouring hydrochloric acid on protesting swimmers. (The Associated Press)

Here he is with John Lewis and Lester McKinnie in Nashville, Tennessee, April 30, 1964, his heavy tape recorder slung across his chest, mic in hand.

There he is in Greenwood, Selma, Atlanta, Tuscaloosa, Nashville, and Montgomery. I look for him in moving film, as well, stopping and starting historic marches with my cursor to scan the faces for his. My father is a Zelig, front and center.

A Protean Year: 1964

In 1974, Howard University Press published my father’s book, The Trouble I’ve Seen. The book focuses mainly on the national events of 1964 that my father covered for ABC news.

After that year, the Movement would never be the same. So many emotionally stirring and politically significant events were crammed into that year—Doctor King’s Saint Augustine campaign that helped to pass the Civil Rights Act; the Mississippi summer with its Freedom Houses and the murders of Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman, black churches stirred to fervor by the Movement, then put to the torch or dynamited by Klansmen or their cohorts; the formation of Mississippi Freedom Democratic party in Jackson and its betrayal by the national Democratic Party on the Boardwalk in Atlantic City. The list seems as long as those marches by day and night on Southern streets and highways that merge in my mind into a vision of marching as an end in itself. The illusion stood that by simply walking forward one could really get someplace…. The troubles I’ve seen derive from us all. And in finding out what happened in the South, to us during 1964, we find out things about ourselves who live in the storm of conflict called America. (3)

The Trouble I’ve Seen is chronicle and witness, but it is also a record of my father’s rapid education in America’s racism; much of this book is literally about being a white reporter covering a black movement, as much as it is about the Movement itself.

Beyond describing these events as I saw them, the book describes me, a white writer no longer young, who was learning about black and white American realities…. I wish I could say at this point that the book you will read on 1964 was a uniformly expert, well-written, whole. It wasn’t, isn’t. The beginning, in particular, contains passages that on rereading make me wince for their social or political naiveté and wrongheadedness, their literary awkwardness. At their most elemental level, these deficiencies include using the word ‘colored.’ Even though black had not been declared beautiful in 1964, ‘colored’ was and always has been a demeaning racial description, suggesting something that children do with crayons to figures in a coloring book. (3-4)

My father agonizes over questions of what is now called his “gaze,” and he castigates himself, recalling an unexamined upbringing, shamed by mistaken assumptions, tones and misconceptions that may have resulted in poor reporting:

By the end of 1964, many Americans had been altered. The introduction of my personal relationship to employers and to black and white participants in our drama seemed necessary to understand my point of view because the point of view conditions every observation and affects the “truth” of what is observed. (21)

The book opens with my family—my father, mother, and ten-year-old brother, Sean—living in Mexico City in 1963, where my father served as ABC News’ Latin American Bureau Chief. (I was not born until 1967.) This was an easy gig, and they lived like kings on ABC’s dime. My brother was enrolled at an American school, while my mother presided over a large house and bought up beautiful things at markets and antique stalls for pennies. Life was not bad for “two kids from Brooklyn,” as my father liked to call my mother and him. My father writes that on that Sunday, September 15th, he had walked leisurely into the United Press International Office to check what seemed like an unusually active Teletype machine. At first, he did not believe what he was reading. Surely, he thought, his poor Spanish was mangling his understanding:

At first I did not trust my translation because the Spanish words under the Birmingham, Alabama, dateline told a story that was hard to believe. I went over it again, word for word, and it was so. Someone had exploded a bomb in a Negro church and four young girls were killed. I tore off the copy and sat down with it by the window. I suppose all decent men and women who read the story anywhere in the world filled with the same emotion—a grab of pity at the heart for young innocents slaughtered, grief in mind for the parents, and quick hate in the blood for those who did it. Any child’s death wounds a parent who hears of it because it is a reminder of his child’s mortality. So my son Sean and the four Negro girls fused, and that beautiful Sunday morning lay streaked outside the window. Later, I would turn against those tears as a cheap coin of indignation, an easy self-absolution for my sins of indifference over the years at what America was doing to Negros. And to itself. (11)

My father lobbied ABC to move him and the family to Atlanta to report on the Civil Rights Movement, and they agreed. But before the move could happen, JKF is assassinated in Dallas and my father is sent to cover the aftermath. (He is in the famous hallway crush of reporters at the Dallas police station, and one can hear him yell out to Oswald: ‘Did you fire that rifle?’)

Here he is interviewing Janet Jada Conforto, a dancer with a spotty memory, who worked at Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club. My father exudes old-fashioned newsman comportment and speech; the swivel chairs are interesting. I love his sign off: “The reasons for [the assassination], those are hard to pin down, as the portrait of Jack Ruby emerges, piece by piece.”

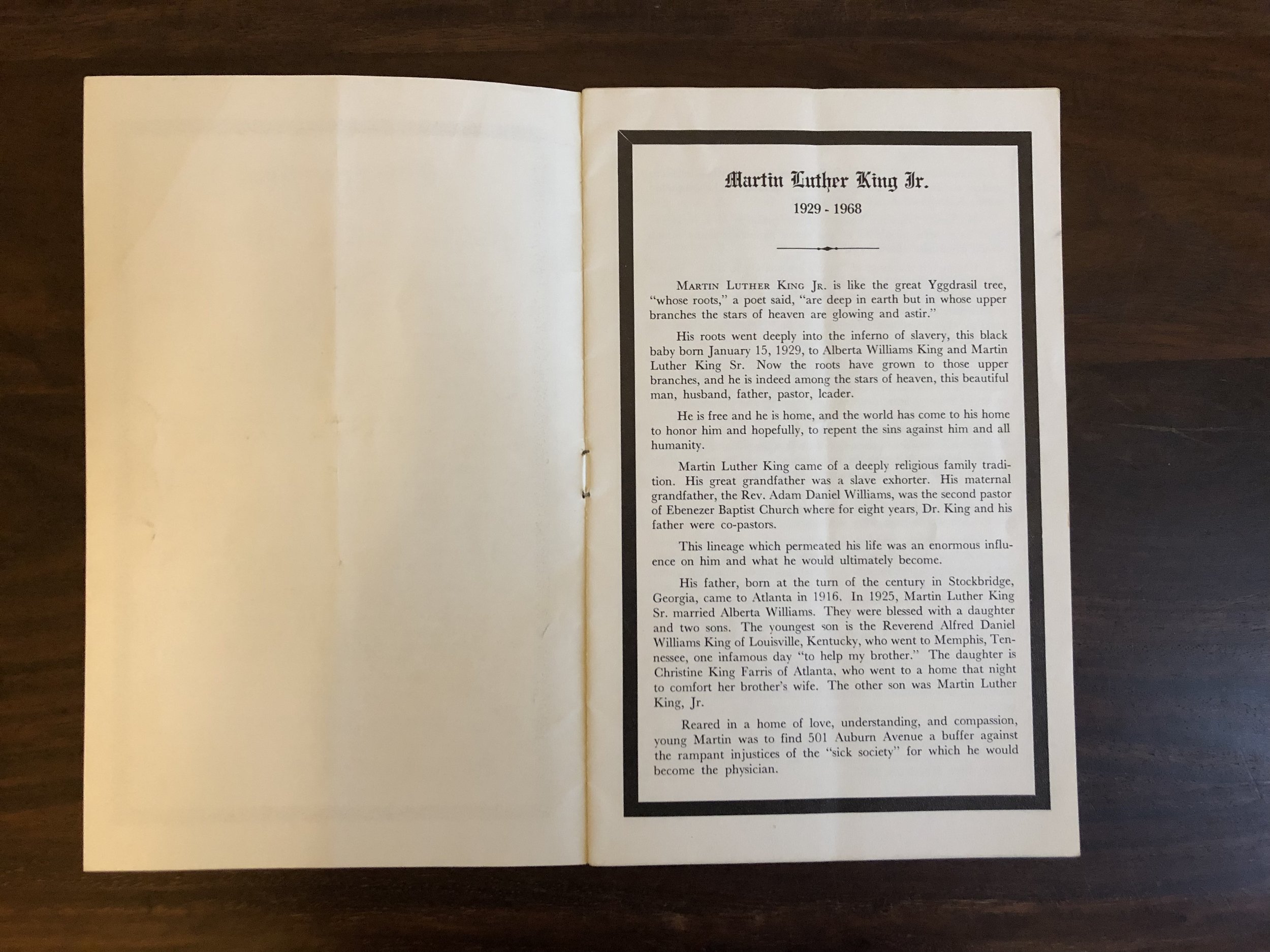

After Dallas, my father flew to Atlanta to make some preparations for the coming move, and on Thanksgiving, 1963 he went to hear Martin Luther King Jr. speak at Ebenezer-Baptist Church. In five years, King himself would be eulogized there—my father the only white man asked by King’s entourage to view the casket at the undertakers. (He would regret not accepting this offer for the rest of his life, having thought that a white man’s face had no place in that room.) My father records this first encounter in antiquated language:

Dr. King, when I first saw him, seemed Oriental, a face from a Japanese print, light-skinned and broad with ovoid eyes that sometimes looked in and other times out, but were always part of a self-contained expression so set that it was masklike. (17)

Though my father was not impressed with the beginning of King’s Thanksgiving Day speech, by its end he had been transported and transformed:

These words on paper can only suggest the cadences that Dr. King was building, his voice deliberate and outraged as the crimes of Birmingham and Jackson were recounted, then gathering emotional momentum with remembrance of slavery. I was surprised to hear slavery, a dead historical issue for me, introduced. But the grandparents of many of the congregation had been slaves, possibly the parents of a few. Dr. King was touching a racial remembrance, speaking of known things among them in a way that no white man could speak because his American existence did not start in 1691, because his children could not have been in the Birmingham church. So, this bond between speaker and listeners made any white person in the audience an eavesdropper on a family discussion. But the eavesdropper was also part of it, the condemnation bitter in him as well as the hope, the irresistible hope that Dr. King next began creating, making the church bloom inside when the country outside seemed to be shriveling. (20)

It is a powerful speech, King outlining a litany of complaints, each question answered and rounded off with the refrain: “Thank God, it is as well as it is” (22). The speech had been captured on my father’s giant reel-to-reel tape recorder, one he would carry with him throughout the South, the one captured in photographs of him in action, the heavy thing slung across his chest, the recorder absorbing and retaining seconds and minutes of American history. I know now that my father had been listening to this Thanksgiving Day speech the afternoon I came home to find him crying at the picnic table. While the tapes are imperfect, King’s sonorous voice is clear and cadenced, exhibiting the oration of a master:

Though there are trials and tribulations ahead, thank God it is as well as it is. Even though America has a long, long way to go before she realizes her dream, thank God, it is as well as it is. Even though we have met the storms of disappointment, and the jostling winds of hatred are still blowing and the mighty torrents of false accusations are still pouring on us, thank God, it is as well as it is. Even though we do not know what tomorrow will bring, thank God, it is as well as it is. Even though we know not what the future holds, we know who holds the future. Thank God, it is as well as it is. Even though we are burdened down with the agonies of life, even though we can’t understand, even though we cry out my God, my God, why?—thank God, it is as well as it is. This morning it is well with my soul, that is what we can cry on this Thanksgiving morning. (21)

My father returned to Mexico forever changed.

The pilgrim mood those words inspired remained with me long after the service, and far away in Mexico City, watching wood-paneled manger scenes take shape along Reforma, they made me certain that I was going where I belonged. It was time to go. After 1964, the South and the rest of the country would never be the same again. And although the year hung for only a moment in our history, the agonies and glories of 1964 were long ago locked in the national seed. (21)

The South

Once relocated in Atlanta, Georgia my father began traveling to Southern states—Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and to its towns, St. Augustine, Nashville, Notasulga, becoming immersed in the issues, as well as connected to the major players of the day: King, Lewis, Young, Abernathy, Vivian. He traveled alongside these men, and got to know them; in such conditions, I imagine, connections were accelerated and, if I may, feelings deepened. He interviewed King many times; in fact, the first time he met King my father had, at the last minute, agreed to fill in for an interviewer at a Southern television station. (I have searched for this film but it is lost to time.)

The Trouble I’ve Seen: The Lead

The first story my father covers in The Trouble I’ve Seen—in a section called The Lead—begins at the end, in Selma, March 1965. After a brief Introduction, the next section first appeared as a dateline article in The Washington Post. A month earlier, on February 26, a young man named Jimmie Lee Jackson had been shot and killed by a state trooper, while he peacefully protested voting rights issues in Marion, Alabama. Members of the SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) had then urged a march to Montgomery, resulting in Bloody Sunday. On the second march, Cager Lee, Jimmie’s grandfather, walked alongside Reverend King. While marching, he explained to my father how he had come to accept his grandson’s death:

‘Yes, it was worth a boy’s dying,’ Lee said as he walked in the front line with the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. ‘He was my daughter’s onliest son but she understands. She’s takin’ it good.

And he was a sweet boy, Not pushy, not rowdy. He took me to church every Sunday, worked hard. But he had to die for somethin’. And thank God it was for this.’

Behind him stretched the column, black and white, pennants fluttering, winding down Broad Street, the main thoroughfare of Selma. A record shop blared, ‘Bye-Bye Blackbird’ over a public address system. And cars carrying white boys went by bearing slogans like, ‘Open Season on Niggers—Cheap Ammo Here’….But Lee seemed not to notice.

‘There was but one white man said he was sorry about Jimmie Lee,’ he said. ‘He sent me the biggest box of groceries—rice, coffee, sugar, flour. And he called me and said, ‘I’m so sorry. I don’t know what to do.’ But no other white man said a word. And I’ve lived and worked in Perry County ever day of my life.’

The marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge over the muddy Alabama River. A federalized National Guardsman walked through the weeds along the bank below, looking for trouble that never came. At the end of the bridge, where Negroes were routed by state troopers and posse men two Sunday’s ago, stretched the commercial clutter familiar to the approaches of many American towns: a hamburger stand, gas station and roadside market.

‘….This is the place where the state troopers whipped us,’ Hosea Williams, aide to Dr. King, was crying out. ‘The savage beasts beat us on this spot.’….

‘How could you ever think a day like this would come?’ asked Lee to himself as much as to a reporter. ‘My father was sold from Bedford, Virginia, into slavery down here. I used to sit up nights till early in the morning to tell of it. He’d tell me how they sold slaves like they sold horses and mules. Have a man roll up his shirtsleeves and pants and told: ‘Put on your Sunday walk.’ So they could see the muscles, you know.’ (7-8)

In a footnote, my father has written: “I wrote this article a few months after 1964 ended and the Selma-to-Montgomery march began. It is included so that the sacrifice of Jimmie Lee Jackson is recorded and remembered” (9).

Scenes from the Movement: Selma

I have found my father in many pictures of that long, multi-week march, and he’s even been spotted in moving film. It is hard to describe how much he loathed George Wallace, the governor of Alabama who tried to thwart the march at every turn; he cursed the man’s name until the day he died. Wilson Baker—on the list of the irredeemable—was a close second to Wallace in my father’s estimation.

Here he is on February 1, 1965 on the cover of the New York Times, at the moment Selma’s Public Safety Director, Wilson Baker, arrested King and his followers: “Each and every one of you is under arrest for parading without a permit.’’ Incredibly, in this photo, my father is standing in the exact middle of these two men, a fitting place for a journalist.

Here he is smack dab in the middle of that day’s most iconic photo of Pettus Bridge. I am not sure he knew he had been immortalized in this photo; it would not have occurred to him to look for himself. (Flip Schulke / Corbis)

Here he is in the rain on the road from Selma heading to Montgomery. His physical form here knocks me out. How does a man die with such powerful arms? (The Image Works)

Here he is in the final stage of the Selma March. My father has said something that has made people laugh, and Andrew Young is looking at him, as King and Coretta walk hand and hand behind them. The scene is alive with color, there are lots of flags and the reds are especially vivid, as if all are bloodied; it is the next best thing to having my father alive again. (The Image Works)

The Trouble I’ve Seen is organized into the four seasons and then broken down further into chapters. All the action is seen and experienced by my father, doing his best to align himself with a clear vision of truth. He writes:

This book is concerned with how America was revealed to me in that year of bitter bloom. The revelation was sometimes episodic, sometimes patterned and always laced together by my involvement. The involvement and my reflection at first are basic and naïve. I think they develop with experience. At the close of the book, a different American is writing than the one who began it. (21)

The Trouble I’ve Seen: Winter

It is my father’s first time seeing actual, living Klansmen. My father would soon get to know the Klan up close and understand their not-at-all-funny omnipresence, but during his initial visual baptism into the South, he found these costumed men both comical and anachronistic:

It was a raw Sunday in January and the frost was on the peach trees when I saw the six Klansmen, wind billowing their white satin robes, conical hoods upright, faces uncovered, coming down Forsyth Street in the heart of Atlanta. They were young and old, fat and lean, but their faces were set in uniform hardness, eyes clear or rheumy, staring straight ahead. They seemed an apparition from the past, out of joint with the street where undistinguished old buildings merged haphazardly with new ones, and with the well-dressed strollers. I felt as if a band of World War doughboys in their puttees, round steel helmets, and hobnailed boots had suddenly swung down the sidewalk. Some spectators smiled in their confusion. The Klansman did seem the ultimate absurdity in our male mentality that produces groups that run around in fezzes and fraternal orders with their ritualistic mumbo jumbo. One stout Klansman from the rear looked like a corpulent beadle waddling in his cassock. And yet, there was something else, a cross between Halloween spookiness and vestiges of the old dread those ghostly trappings had once inspired. To complete the anomaly, these Knights of the Invisible Empire were not carrying guns or bullwhips, but picket signs.

‘Don’t Trade Here!’ said the neat, professional lettering. ‘Owners of this business surrendered to RACE MATTERS.’ (25)

Family History

The South was not the North. Besides being stationed in the Army in North Carolina, my father had little experience of the South, and he intuited the complicated place he occupied as a white reporter; he knew he was not a disembodied eyeball. He had come from a family of Irish-Catholic immigrants who had tripped the light fantastic out in Sheepshead Bay before devolving into dysfunctional sentimentality, drenched in alcohol. He first sensed the inequalities between whites and blacks at his family’s golf driving range in Brooklyn on Avenue X. My father was the “Little Master” of the course, fawned over and indulged. The family employed black ball “boys” to pick up golf balls, but did little to protect the dignity or safety of their workers. White golfers found it amusing to try to hit the black men collecting the balls while my grandparents did nothing to stop them. He writes: “They worked for virtually nothing and although my father had qualms about what he paid them and tried sporadically to be fair, he lacked the moral staying power to establish a truly just reaction” (12). One worker, Willie Jameson, (black men were called by their first names, all white men by their last, prefaced by the respectful and humanizing “Mr.”) was hit so many times with golf balls in the face that he lost vision in one eye. “Finally,” my father writes, “when the golf business failed, Willie drifted off somewhere half-blind” (13).

Somehow, my father emerged from this family with a brain and a conscience. At eleven years old he took an IQ test at Columbia University and, after receiving a score of 175, was henceforth known around the house as “Little Shakespeare.” He saw through things early and wrote penetrating prose; journalism was the natural career choice. He went to Brown University until he got kicked out for writing other people’s papers for money, attended Boston University briefly, wrote for Stars and Stripes in the Army, then wrote for newspapers, and moved on to television reporting. He was first a rewrite man at The New York World-Telegram and Sun, where he met my mother, and later a news writer, editor and producer at NBC. He joined ABC in the ‘60s.

1960s Newsmen

In the 1960s, reporters wore suits and carried giant tape recorders with cross-body straps, while cameramen wielded heavy, awkward film cameras, and print photographers scurried around with small still ones. My father’s crew loaded and unloaded twenty heavy pieces of equipment day-in, day-out. Processing the news for a nightly broadcast was complicated; scripts had to be written and filmed, interviews spliced and edited, and then everything packaged and sent to New York producers through the mail. After a writer had expended all this energy, the pieces might get 50 seconds on national news. The work was intense and multifaceted, and one could never be sure if any of it would make it on air. With a story this elemental and essential, my father was often frustrated over his producers’ decisions to air or not to air certain stories; he could see the import, but he felt that the North, at times, really didn’t understand what was happening. The racial stories coming out of the South weren’t blips; there was societal change afoot in its entire dangerous and chaotic churn.

Beyond the technical and editorial challenges, Northern newspapermen reporting on the South were regarded with suspicion and hatred. They were considered and called Communists, “Jew carpetbaggers,” and agitators from the North. All were considered “white n----- lovers.” Newsmen were met with signs taped to municipal offices in dusty towns reading: “Newspaper men are not needed or wanted.” Reporters and cameramen were routinely taunted and beaten; the crowds went after the cameramen and their film first and most viciously, perhaps believing that images would out their evil faster than a reporter’s words. My father and his crew were targeted several times. Cameras were broken, heads beaten, and recorders smashed.

My father describes one such dangerous day in Notasulga, Mississippi, when, a year after the Tuskegee school integration fiasco of the year before, as six black students were bussed to matriculate at what was then called Macon County High. In Tuskegee, Governor Wallace of “segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever” fame, refused to comply with the implementation of Brown v. Board of Education. He shut the Tuskegee High School down, and then declared the state would reimburse parents if they sent their children to an all-white private school. Federal judges shut him down. When the last six black students at Tuskegee were matriculating at Notasulga, everyone braced for the violence that inevitably came. It is chilling to listen to my father’s blow-by-blow coverage of the events; he sounds like the unhinged radio announcer who chronicled the Hindenburg disaster. At one point he’s so upset he’s nearly crying, swearing, “I’ve never seen anything so violent in my life,” though he had not yet seen St. Augustine or Selma:

The troopers ordered us to stand with a few dozen newsmen directly in front of the rednecks, who were mumbling about outside agitators. We were shooting sound. A word of explanation is needed here. A cameraman shooting a silent carries a small hand camera, which gives him great freedom of movement. A sound camera is a big, bulky affair mounted on a shoulder harness and attached by cables to the sound recording device carried by the soundman. This umbilical arrangement limits movement and increases the vulnerability of the men and record they are trying to make. We waited; considerable tension was in the air.

Across the street was a roving sheriff from Dallas Country (about a hundred miles away) surrounded by members of a special posse he used to keep Negroes in line. His name was Jim Clark and he was destined for eventual fame in the city of Selma.

The bus came over a knoll and rolled towards us. A bus carrying school children. That was all, and your stomach knotted. The rednecks crowded in, shoving and cursing, the bus halted directly in front of us, a little cloud of exhaust wafting up, and Sheriff Clark and a man in civilian clothes jumped aboard. The faces of Negro children, vague behind dusty windows, turned to them and suddenly there were screams and thuds from inside. Some body threw a firecracker that sounded like a pistol shot. The red necks pushed into us, swinging canes. One caught Blair on the head, and another cracked his camera lens. Somebody looped a cane handle over the cables and started tugging, and I grabbed the cane to keep him from cutting the sound. ‘Get ‘im, get ‘im,’ a redneck yelled. Bob continued filming, I continued talking into the tape recorder, mike held in one hand while the other tugged at the cane. The racket from the bus was awful—girls’ voices crying hysterically, and I thought the children were being beaten. The reality of the scene was hard to believe even as it was happening. But suddenly a slim white youth in his twenties was thrown to the floor. He lay on his back, moaning and yelping, as a law officer [Jim Clark] jabbed at this stomach and genitals with a cattle prod, a battery-driven shock device used to get cows moving. Laid on human skin the prod produces excruciating pain. The state troopers watched the youth being worked over but did not intervene. (54-55)

My father reaches the man, Vernon Merritt III, to learn he was a freelance photographer who had joined the bus in Tuskegee to take pictures of the students as they were driven towards Notasulga. Later, when Merritt recovered from the beating and sent the day’s film by mail to his employer, the package was delivered empty; someone had slit the envelope open and removed the film. The potential power of the images captured by newsmen scared these people. From then on, news cameramen insured their packages for $1500, and the film got through.

The Tapes

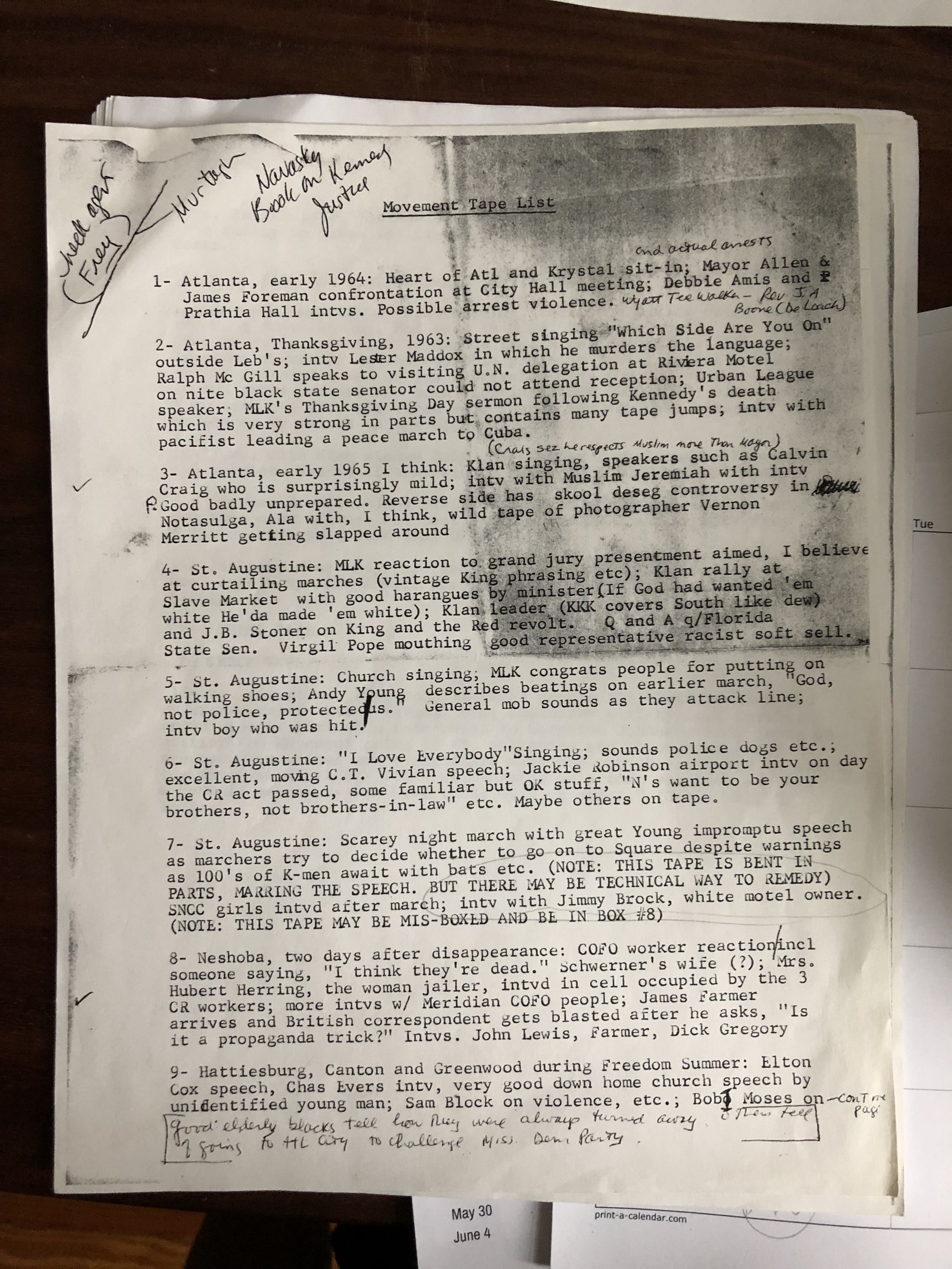

When my father died in 2005, I donated his tapes to Emory University. While the librarians at Emory provided me with a professional accounting of what was on the tapes, it is my father’s typed-out (and annotated) list that I usually refer to because he’s highlighted what to him were the most salient pieces of sound.

Notes such as: “# 2 - Atlanta, Thanksgiving, 1963: Street singing ‘Which Side Are You On’ outside Leb’s; interv Lestor Maddox in which he murders the language.” “#3 Reverse side has skool deseg controversy in Notasulga, Ala with, I think, wild tape of photographer Vernon Merritt getting slapped around….” “#4 St. Augustine: MLK reaction to grand jury…Klan rally at Slave Market with good harangues by minister (If God had wanted ‘em white, He’da made ‘em white).” “#7 St. Augustine: Scary night march with great Young impromptu speech as marchers try to decide whether to go on to square.” “#8 Neshoba, two days after disappearance: CFO worker reaction incl someone saying, ‘I think they may be dead.’” “Interv. John Lewis, Farmer, Dick Gregory.” “#9 Hattiesburg, Canton and Greenwood during Freedom Summer: Elton Cox speech Chas Evers intv., very good down home church speech by unidentified young man….” “#11- Colbert, GA: Lemuel Penn killing, inc. with police chief…King and Co. at the burned-out church three worker had been visiting….” “#12 Intv. With Klan Wizard Robt. Shelton in Tuscaloosa as he rambles and predicts Reds will assassinate MLK.”

Decades before, my brother had transferred the old-fashioned reel-to-reel tapes onto cassettes for easier use with Dad’s cheap Radio Shack recorder. The original tapes of shiny grey audiotape had, over time, sometimes bent, stretched, and twisted, rendering patches momentarily inaudible. Plus, my father was no engineer, and occasionally entire sections were wiped out mistakenly, while others had become so sped up that interviewees sound like querulous, indignant mice. His tape descriptions often have little addendums like: “TAPE SOMEWHAT OFFSPEED” and “NOTE: THIS TAPE IS BENT IN PARTS, MARRING THE SPEECH,” and then his own reporting failures, “intv with Muslim Jeremiah with interviewer P. Good badly unprepared.”

One tape is backwards, making the event sound absolutely demonic. In addition, the tapes sometimes bleed through and interrupt each other—a Klan rally will suddenly have a dash of the Haitian Invasion in it—so they offer a layered, sometimes scrambled, accounting of my father’s life work and the world.

Most, however, are absolutely riveting sound artifacts, and I listen to them in awe. Time collapses. Time is redeemed. I listen to them on the subway some days, mostly by accident, when my iPhone is on shuffle. That can be truly shocking: I’ll be transported to a street somewhere in Mississippi in 1964 on my way to Midtown Manhattan. Suddenly the voice of an Imperial Grand Wizard will be in my ear, yammering on about how the Klan was like “dew, spread out all over the South,” when I had just been listening to a Tom Petty song.

The Trouble I’ve Seen: Spring

Disorder in Florida

St. Augustine, Florida was a place my father spoke of as his childhood vacation spot—a place where the water smelled like sulfur and where the beaches were pure white sand, nothing like our rocky Connecticut coast or his Brooklyn beaches. He’d remind me that this Floridian city was also the nation’s oldest slave port; that was never, ever to be forgotten. He felt that the white sands of his boyhood may as well have been soaked in bright red blood, so violent were the clashes between blacks and whites he witnessed upon his adult return.

That spring in St. Augustine, things were simmering to a boil. In a chapter called “Schizophrenia By the Sea,” my father witnessed firsthand the now famous activity at the Monson Motor Lodge, owned by a Floridian named Jimmy Brock.

Here is my father reporting on June 11, when Martin Luther King Jr. and nine of his colleagues were arrested and jailed for refusing to leave the segregated Monson Motor Lodge where they had attempted to eat at its restaurant. (The Associated Press)

Brock had locked the doors and called police, nearly begging to King to take his non-violent “army” elsewhere. Things really devolved at the Monson on June 17th when a white activist named Al Lingo rented a room and invited black compatriots to swim as his guests. Once his guests jumped in, Brock went bonkers.

Brock ran out, beside himself, only to be told by Lingo that he had a right to invite friends to swim with him. A mob of segregationists quickly gathered. Black bodies in a pool with whites touched sexual nerves. State troopers held a thin line between order and violence. Brock was almost hysterical. He ran to the pool with gallon cans of muriatic acid, a relatively harmless disinfectant when diluted, and dumped them in...Television cameras, previously alerted by SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], captured all the wildness of the bizarre scene. Across the street under a palm tree, Dr. King, released from jail on bail, calmly watched. Finally a city policeman took off his shoes and dived into the pool.…

‘Let’s kill all the goddam n-----s,’ a jarhead cried, and if desire was deed it would have been done.

Brock, weeping with frustration, ordered that defiled water drained. Before this was done, two county deputies arrived from one of the tourist attractions, an alligator farm, with two big cartons. Each held an alligator about four and a half feet long. After the pool was drained, scrubbed, and refilled, it was understood that alligators would be thrown in at the next dive-in demonstrations. (101-102)

Alligators. St. Augustine was going to blow. My father, only scared of lightning and praying mantises, bought a gun:

I bought a gun, a 25-caliber Italian automatic, the first weapon I had ever felt the need for, including hectic times of Latin American revolt. The colonel commiserated with us on our problems. His role was obviously to soothe the savage press. I remember telling him:

‘Colonel, we’re fed up with platitudes. Any good cops could control this if they wanted to. These bastards are threatening us and I’m telling you—and you can tell them—I’ve got a gun and if they come around bothering us I’m going to shoot the sons of bitches.’

In retrospect, I sounded overly dramatic. But in defense, it was getting hard to know how to behave. A grim Alice-in-Wonderland atmosphere existed in those days; bizarre things were done but with a kind of grotesque logic. An editor named Elliot Bernstein had come down from New York to help with production. Jimmy Brock felt he was vulnerable and graciously gave him an eight-inch length of pipe in his car should the jarheads attack. State troopers looking for troublemakers stopped Bernstein and found the pipe. Was he arrested? No. They politely took it from him and wrote out a neat receipt, noting under “Item,” one eight-inch pipe.

‘You can pick it up,’ they said, ‘after this mess is over with.’ (94-95)

The mess—the violence—came with the night march, a night when my father and his cameraman witnessed an eerie scene, and also became part of it. The night of the march, Andy Young led a group of marchers toward the Old Slave Market as a group of malevolent whites led by the chieftain of Florida’s KKK, Connie Lynch, held forth, whooping and hollering, spewing their racist bile. Lynch swore by violence and was proud to say it: "I believe in violence! All the violence it takes to scare the n------s out of the country or to have 'em all six feet under!" To know the soul of Connie Lynch, one need only read his comments regarding the four dead girls of the Birmingham church bombing:

Someone said. “Ain’t it a shame that them little children was killed?” Well, in the first place, they ain’t little. They’re fourteen or fifteen years old—old enough to have venereal diseases, and I’ll be surprised if all of ‘em didn’t have one or more. In the second place, they weren’t children. Children are little people, little human beings, and that means white people. There’s little monkeys, but you don’t call them children. They’re just little monkeys. There’s little dogs and cats and apes and baboons and skunks and there’s also little n-----s. But they ain’t children. They’re just little n-----s. And in the third place, it wasn’t no shame they was killed. Why? Because when I go out to kill rattlesnakes, I don’t make no difference between little rattlesnakes and big rattlesnakes, because I know the nature of all rattlesnakes to be my enemies and to poison me if they can. So I kill ’em all, and if there’s four less n-----s tonight, then I say, “Good for whoever planted the bomb.” We’re all better off. (89)

The chief of police, Virgil Stuart, met the marchers in the street and explained in terse terms that they would not be protected from Lynch and the crowd waiting for them with clubs and chains.

‘Don’t come any further,’ Chief Stuart told him, ‘unless you are prepared to get into serious trouble.’ A flashbulb popped. ‘Don’t turn that camera on me,’ he warned. ‘I don’t want my picture taken. You take my picture you go to jail.’ The chief had a reputation for a bad temper, also the reputation for being a good police officer when faced with anything other than racial disturbances where his private passions came into play. His voice tight with anger at this unaccustomed role of counselor, not authority, to Negroes. He said to Rev. Young. ‘It is my strong advice to go on back.’

‘We kind of feel,’ said Young, ‘that the only way we’ll ever really have any respect or….’

‘Now listen, I’m not going to argue with you at all. My advice is for you all to go back. If you don’t, my firm conviction is that some of you are goin’ to get hurt and some other people are gonna get hurt. It’s my job to protect this city. Now you’ve gone just as far as you better go. We can’t protect you any further.’ (80-81)

My father’s recorder then records a tremendous speech by Reverend Young, delivered extemporaneously, in the face of certain violence. The speech began:

‘Tonight is the night we decide if you want to be free. For three-hundred years we’ve been kept in slavery through fear. If you can keep a man afraid, you can keep him from being a man…. The chief of police has advised us not to march down in the block of the Slave Market. He said he’s not sure he’ll be able to protect us. Well, I think we’ve been living this way for some time now. And I think this is really one of the first times I’ve ever been in a situation where a Deep South police chief was even concerned about protecting me.’ (83)

At the conclusion, Young asks the cameramen to stop filming while he led the group in the Lord’s Prayer.

My father describes what happened next:

What followed was unbelievable to me.

The Negroes marched again as soon as the Simpson ruling came down. Young led it, and I watched him get knocked down on three street corners around the square, punched, blackjacked, and kicked. In each case, policemen intervened only after the whites had vented their wrath. Half-a-dozen demonstrators were beaten that night and carried to segregated Flager Hospital for treatment. The march was eerie to watch, to stand in the night in this now famous city and see people you respected walk down a sidewalk and to know that it was a matter of minutes before someone would knock them down, and to know that the police would not prevent it, and you could do nothing. (92)

There it is, the strange, necessary detachment of the journalist, watching things unfold, duty-bound not to interfere, not to have reactions, not to lean one way or the other even when the truths at hand were in such stark relief.

His reporting tapes of this night are frightening. That night his cameramen were attacked and his tape recorder was ripped from him. Klansmen taunted the newsmen, agitating the marchers, churning the scene forward. One hears shuffling feet, yelling, and dogs barking as one man shouts, “He's got a nice tape recorder right there!" Then more chaotic footsteps, scuffling sounds, and more dogs barking and barking and barking.

The dogs barking embody the inchoate anger, the cruelty, the baseline savagery and insanity of it all.

I am also in possession of some of his crew’s film from this night. A few years ago, I spent a few surreal and elated hours hunting ABCs archives for my father’s work. The film loop is a compilation of news stories, ending, bizarrely, with my father interviewing Jimmy Hoffa. But the film is mostly of those roiling days in St. Augustine when my father and his crew were obviously very busy. I hit the jackpot with this long loop of film, rendered dreamlike in parts without sound. In the days before the night march, my father’s crew decided to try to create a visual example of rejection experienced by blacks seeking to enter declared white-only establishments—a little PSA. They show a well-dressed black family trying to gain entrance to various businesses in St. Augustine; as they walk to the doors of hotels and restaurants, the cameraman filmed their feet, turn and walk away. Because of the film’s age, the black-and-white film is nearly a X-ray of events; the film’s whites glow like glow worms, and its blacks smudge to smoky gray in the shadows. They visit the town’s oldest jail. At the jail’s museum, as a kind of sign or joke or God knows what, the camera pans on to a giant puppet of a white policeman with a shotgun who moves back and forth lit by a white light; then, every few moments, a paper maché black prisoner in striped jail pajamas smoking a cigarette (his last one?) pops up like a lamentable Jack-in-the-Box. The message is clear: our prisoners are black. Isn’t that hilarious? My father concludes the St. Augustine chapter intimating that worse was on its way:

Although the next week saw violence intensified on the streets and on the beaches, the alligators never got used in the Monson pool. But on June 25th, the Senate passed the Civil Rights Bill and President Lyndon Johnson was soon to sign it. The bill would probably have passed without a St. Augustine but then the country would not have had the chance to see a certain part of itself…. Summer volunteers were about to enter Mississippi and that certainly was thought provoking. With a sunburned head start on the long hot summer, I left St. Augustine and headed for Mississippi where tragedy was waiting to be played out. (103)

The Trouble I’ve Seen: Summer

Mississippi Murders

The murder of the three Northern civil rights workers during that Freedom Summer—Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman—was told to me early, maybe too early. Somewhere I saw footage of their white station wagon being dragged backwards out of the clay so that I see it just as clearly today, just as I can still see the beaten and distorted face of Emmett Till that so shocked and scared me as a child. This was the world, not Disney, not Westport, not our privileged existence as white middleclass beachgoers. From St. Augustine, my father and crew drove to Jackson, Mississippi, to learn that night that three civil rights workers had gone missing.

We all know the outline of this story: The three men, all Freedom Summer volunteers, had traveled to Mt. Zion Church in Philadelphia, Mississippi after several members of the congregation had been assaulted by Klansmen. The church had then been burned. After leaving the church that night, the three drove towards Meridian, but a group of white men had followed them (including law enforcement officers) and after pulling the three over, the men were brought to a gravel road and brutally murdered, and then buried in their car. My father asked me to imagine the unholy terror of that night, and other nights like it; I tried and succeeded. Like St. Augustine’s turmoil, the absolute horror of these murders changed the country’s perception of what was at stake. My father and his crew sped on to Philadelphia, Mississippi, promising his NYC producers that there would be the world-over dateline the next day, though the story would unfold for the next month.

One month had passed since the lone station wagon with Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman had entered the city. Now townspeople gaped at the new intruders bringing their lawmen with them. With wheels spinning in fast turns that sent up dusty clouds, we cut across the railroad tracks onto the dirt roads of the colored section. We moved with assurance. Philadelphia could not intimidate our brave procession. The mind kept returning to that lone station wagon that dared to come without protection—three young men with no FBI to guard them or correspondents to chronicle their drive. (126)

He wondered why the three had left the jail at night, which was in violation of all of Mississippi’s COFO (the Council of Federated Organization— an organization on par with SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SCLC, CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, and NAAPC) rules about “night-driving.” He visits the jail where the men had been held, a place that smelled like “urine on stone,” and learns from the jail keeper’s wife, Mrs. Herrin, that they ate a dinner of green peas, a green salad, fresh mashed potatoes, sponge cake, cornbread, and tea before they left the jail to drive to their deaths. Weeks went by. And then the inevitable:

On August 3, on a farm outside of Philadelphia, the FBI found the three who had visited the church a month before us. They were under twenty feet of Mississippi clay, earth piled for a dam under construction above them. Deputy Cecil Price, sweating in the 100-degree heat of the August sin, helped carry the bodies. Each of the young men had been shot, and Chaney had been beaten. Dr. David Spain, a pathologist from New York with twenty-five years experience, examined Chaney: ‘…the jaw was shattered; the left shoulder and upper arm were reduced to pulp; the right forearm was broken completely across at several points; and the skull bone were broken and pushed in toward the brain. Under the circumstances, these injuries could only be the result of an extremely severe beating with either a blunt instrument or chain…. It is impossible to determine whether the deceased died from the beating before the bullet wounds were inflicted…. I have never witnessed bones so severely shattered, except in tremendously high-speed accidents such as airplane crashes.’ (128)

Schwerner and Goodman, both white, had been shot in the heart. Chaney, black, had been obliterated: castrated, beaten to smithereens, and then shot three times.

Weeks before the discovery of their bodies, Lemuel Augustus Penn, then the Assistant Superintendent of Washington, DC public schools, was murdered by members of the KKK. Penn had been driving back to DC from Fort Benning where he and other officers had spent a training weekend. Things were definitely devolving, and yet, dramatic stories were the reporter’s lifeblood and he was both duty-bound and personally eager to go:

I did not stop to pack or plan. I pushed the car as hard as it would go along Highway 85 leading to Athens about seventy miles away. The ’61 Triumph convertible was in bad shape…still, for as long as the car held together I had the old sense of elation to be hurrying toward an important story again. Actually to touch the event that others will only read about or watch on television screen is a narcotic that keeps many hooked to the profession. The job enlivens the sense while it dehumanizes. Reporting stimulates action and defers reflection, and sometimes cripples the ability to reflect beyond immediacy. The man, Lemuel Penn, only existed for me and the public because he had died. About ten hours had gone by since he had passed along the road I drove. His mind had probably been alive with the hundreds of trivial and meaningful thoughts that fill our moments when we are all well and feel no intimations that our mortality is limited. Yet up ahead, cancellation, one of life’s tragic flukes, was waiting. (156)

In a different kind of fluke, my father and brother actually ended up giving useful information to the FBI, helping them identify one of the murderers. My father had been forced to bring the Triumph in to a local garage called the Guest Garage. As he waited for parts for days, the Guest Garage began to take on a center role. My brother, who had joined him on the road, was a sensitive, intelligent, highly intuitive boy—he had my father’s power of discernment—and he did not like what he heard at this garage. When my father expressed urgency, explaining he needed the car to report on the killing of Penn, a mechanic responded: “You mean that n----- committed suicide out there on one seventy-two?” (163). Mrs. Guest piped in to cast doubt that anyone local had been involved, suggesting that the “n------” in the area sure did drum up trouble. Plus, she said “Lots of time, you know, you fix their cars an’ they won’t pay…. You never can tell what a n----- will cook up” (167). As my father went into the garage’s small office for paperwork, my brother noticed, though it was not in any way unusual, a rifle and a sawed-off shot gun hanging on a gun rack on the wall. The third set of gun pegs were empty. When Sean saw that a gun was missing from a rack, he guessed correctly that the reason the slot was empty was because the gun that had once rested there had been used to kill Penn—just six days after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Weeks later, four men would be arrested for Penn’s murder. One of them was a “Herbert Guest, thirty-eight, owner of a garage on Hancock street” (173). Mr. Guest and his compatriots had all been members of the Clarke County Klavern 244, United States of America, Inc. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Trouble I’ve Seen: Fall

MLK Jr.’s Assassination

By the fall of 1964, the country—and my father—were ragged and spent. There had been arrests in the murders by the FBI, but no one felt certain that Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey would truly be held accountable the murders. He felt that Kennedy had done precious little, that the country had needed a reformation and instead received a “feeble renaissance.” His assessment of Kennedy is stinging:

The late President Kennedy, lionized after his death as a man of exceptional moral courage, throws a small shadow in the light from the most brightly burning question in the country’s history. No wonder. He was the end product of intense materialism—the same materialism that mocked our hymns to equality and drove a wedge between man and his noblest impulses…. His mode of existence, his education, and his contacts were produced by an American system that kept the human slag heaps of the white and black exploited well from sight of Newport, Washington, or New York.… He had humanitarian impulses—those stirrings of conscience long misnamed charity. He was capable of the bold gesture that many took as a sign of deep commitment…. In all these things—race, the nation’s have-nots, poverty abroad sometimes tied to United States business policies—President Kennedy was too remote from the hapless of the earth to truly understand them. (235-36)

Johnson, he argued, had used the CRA of 1964 as a kind of national bread and circus, lobbing high-minded verbiage at a problem he himself had not truly fathomed. Though Johnson used the language of the Movement (famously saying in his Civil Rights Act speech to Congress inclusively that “we shall overcome”), he, like Kennedy, had done too little, too late. The place was scorched. My father determines, bitterly: “The response that brought victories like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were based on politics, not morality.”

Looking back at that year, I felt we were not rational and had never been, and that the racial crisis had become a hot light that bore into the American body politic and social soul, revealing truths not only about America’s relation to the Negro but about its relation to itself…. I believe that the Negro Movement in the South gave America the chance to become the Christian nation it had purported to be from its beginning—the brotherhood of man inside a political and social structure existing for the common good. (240)

But it didn’t happen. King’s death four years later in Memphis, where he was supporting striking black garbage collectors, closes the book. As with John F. Kennedy’s assassination, people remember where they were when they heard the news. My father heard it on the radio while driving in somewhere in staid, orderly Connecticut. He wrote, and I believe him: “the emotional impact of the news that Dr. King was dead did damage that has never and can never be repaired to my own capacity for hope for this country” (268). Even on hearing of King’s death, he stopped to scrutinize himself specifically, and the American news media, in general:

I had just that afternoon finished a long piece for the New York Times Magazine called, ‘Which Side Are You On, Boys?’, (which was supposed to examine all the black points of view from Wilkins to Mau Mau chief Jomo Kenyatta.) Why a white writer should get such an assignment to cover purely black turf is one of those involved questions that would require a chapter by itself to be answer adequately. (268)

Without an assignment, my father got on the last plane from New York to Memphis, my mother having borrowed money from God knows who:

At the Memphis airport, I ran into Rev. C.T. Vivian. He invited me to go along with him and Rev. Ralph Abernathy and other SCLC leaders to the funeral home where they would choose a coffin. I remember now, six years later, how sustained I was just being in that car that night. I was coming apart emotionally, but these men who had loved him as least as much as I, were held together by their faith, welded together by the spiritual warmth passing among them. For a nonbeliever, the situation was not enough to convert me to a belief in their Christianity, but was enough to make me wish that whatever they had could be mine…. The choice was made, a casket with ruffles pinched in like a pie crust border, the wood an appropriate mahogany from Africa. Mr. Lewis asked if we wanted to see “him.” The Reverend Abernathy, Vivian, and others went into the inspection room, but I thought that white would be out of place at that moment. (269-70)

He describes the drive to the undertakers:

It was one or two in the morning and the streets of black Memphis were empty and quiet. Storefronts bore slight and scattered signs of rioting that white city officials had exaggerated into virtual insurrection, as they called in the all-white National Guard. The row houses, crabbed and poor, were dark, silent. About two blocks from the funeral home, the car turned a corner and we saw two National Guard tanks a block away, their bulk grinding over the still streets, looming in the dark like some lethal presence on a nightmare dreamscape.

C.T. Vivian said, ‘They bring in the tanks after they’ve done the violence, when Doc is at peace and his people are sorrowing. Good God.” (269)

The Atlantic Monthly did ask my father to write a piece on the funeral, though it was rejected for not being “eloquent enough” (269). My father felt the reason the piece was killed as that it did not reflect how white Northerners wanted to remember King:

Walking in the cortege behind the mule cart bearing his body along Atlanta’s Hunter Street, you think that all your tears had been expended. Then you would be overtaken by a sudden rush of emotion at a recollection of him, or the expression on a face in the procession that was also remembering. His death seemed doubly cruel when the mourners reached Morehouse College campus, ripe with Spring…. Whitman joined the procession then, writing out of time, for him:

When lilacs last in the door-yard bloom’d

And the great star early droop’d in the

western sky in the night

I mourned, and yet shall mourn with every returning spring.

Grief is the proof of love, and the grief felt that day at the death of Martin Luther King, and in the days and weeks that followed proved that the bullet that took him shattered a vessel of love unique in American history. He was a prophetic racial leader, a great preacher, and a social visionary. But the essence of all that he was derived from his capacity to love and his ability to inspire other men to love. On so many nights in small and threatened Southern Negro churches that seemed like arks of light on seas of elemental darkness, he would preach a basic message:

‘We will come to that day when all God’s children will be able to live together as brothers. You know, the white man needs the Negro to get rid of his guilt and the Negro needs the white man to get rid of his fear. And we both need to love each other. So I say Keep on keepin’ on, and we’re gonna make it. Don’t you get weary children, don’t you get weary.’ Then very often, a congregation that next morning would be embarking on a perilous demonstration, singing:

I love everybody,

I love everybody,

I love everybody in my heart,

People say they doubt it,

Still, I can’t do without it.

I love everybody in my heart.

The voice, particularly, pierced the consciousness and the conscience of white listeners. They were an affirmation of faith in a kind of love alien to our experience. Dr. King, tapping his foot to the rhythm, his enigmatic eyes searching the rows of worshipful black faces, would nod in agreement with the word he had heard sung a thousand times. He could not live without it. His philosophy was that simple and that profound…. It was no accident that he was about to come to grips with the system. The tragedy suggests at least a fateful accident of timing. But it was no accident that he was exposed to death in Memphis. It was inevitable happening in a nation profligate with its human resources, a nation that could turn away from one of its best men and leave him to survive as best he could. Inevitably he was drawn to a Southern City where the least of men in the social scale—black garbage workers—needed the kind of support only he could provide. No one else, said the national experience, gave a damn. (270-271)

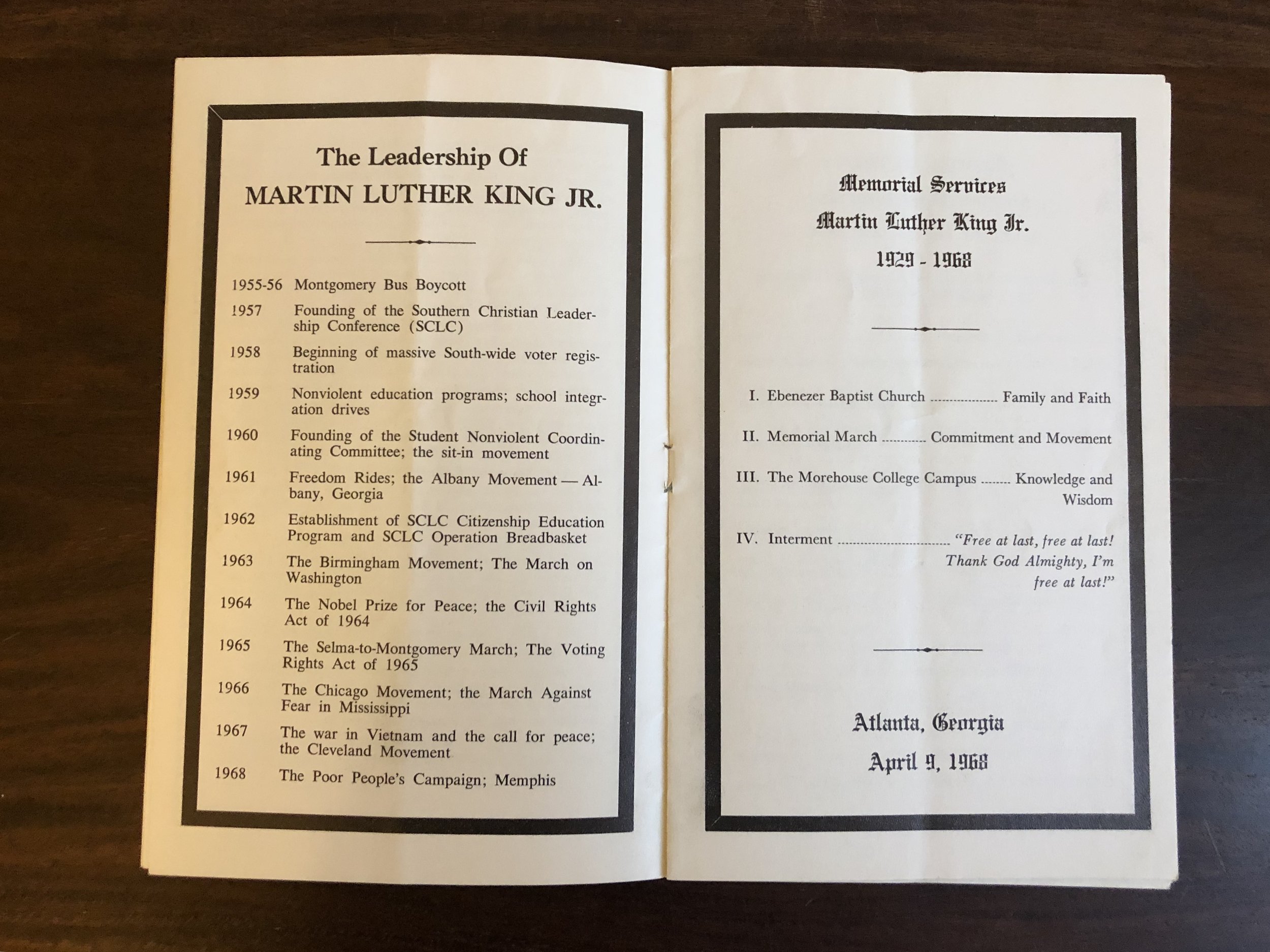

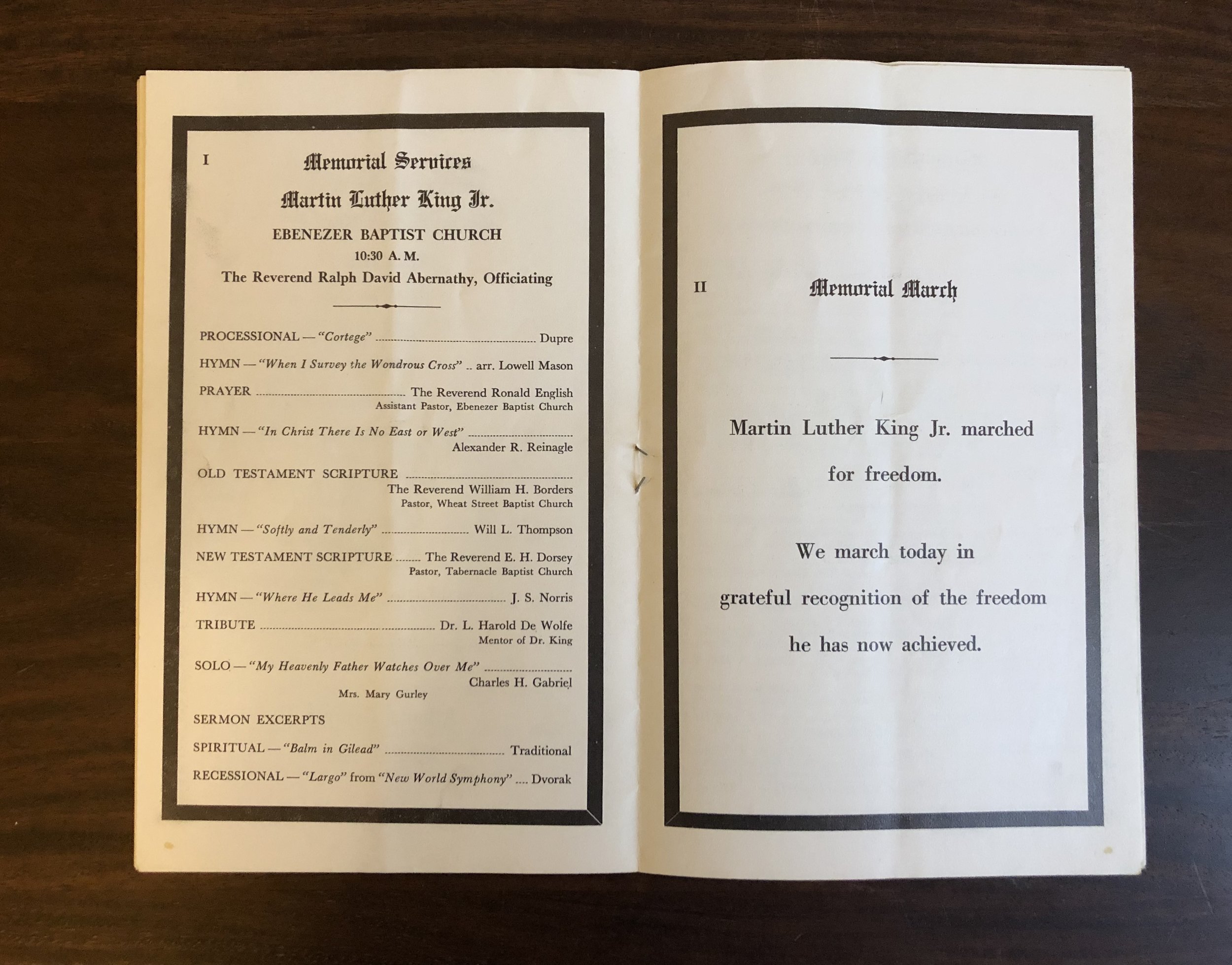

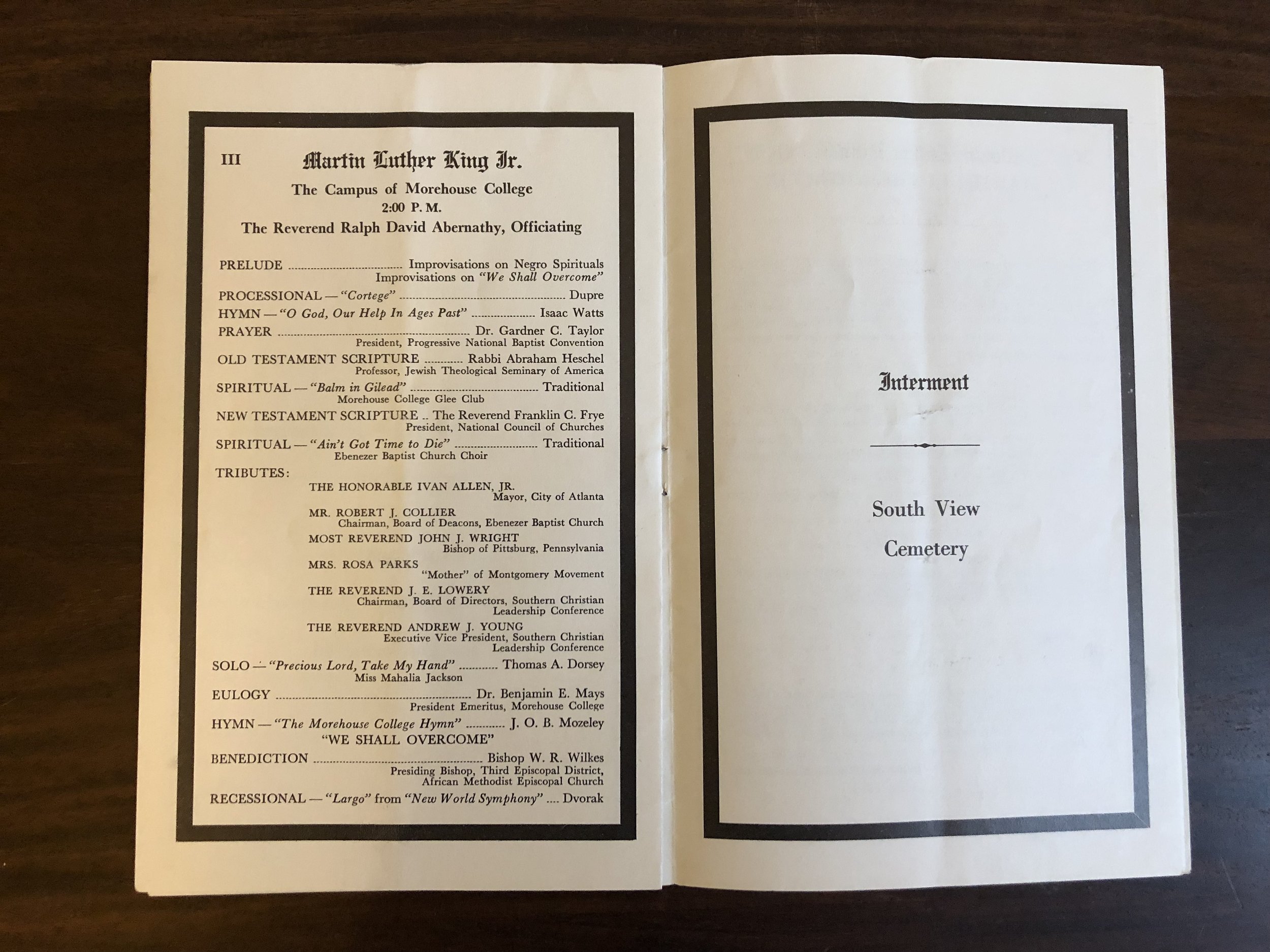

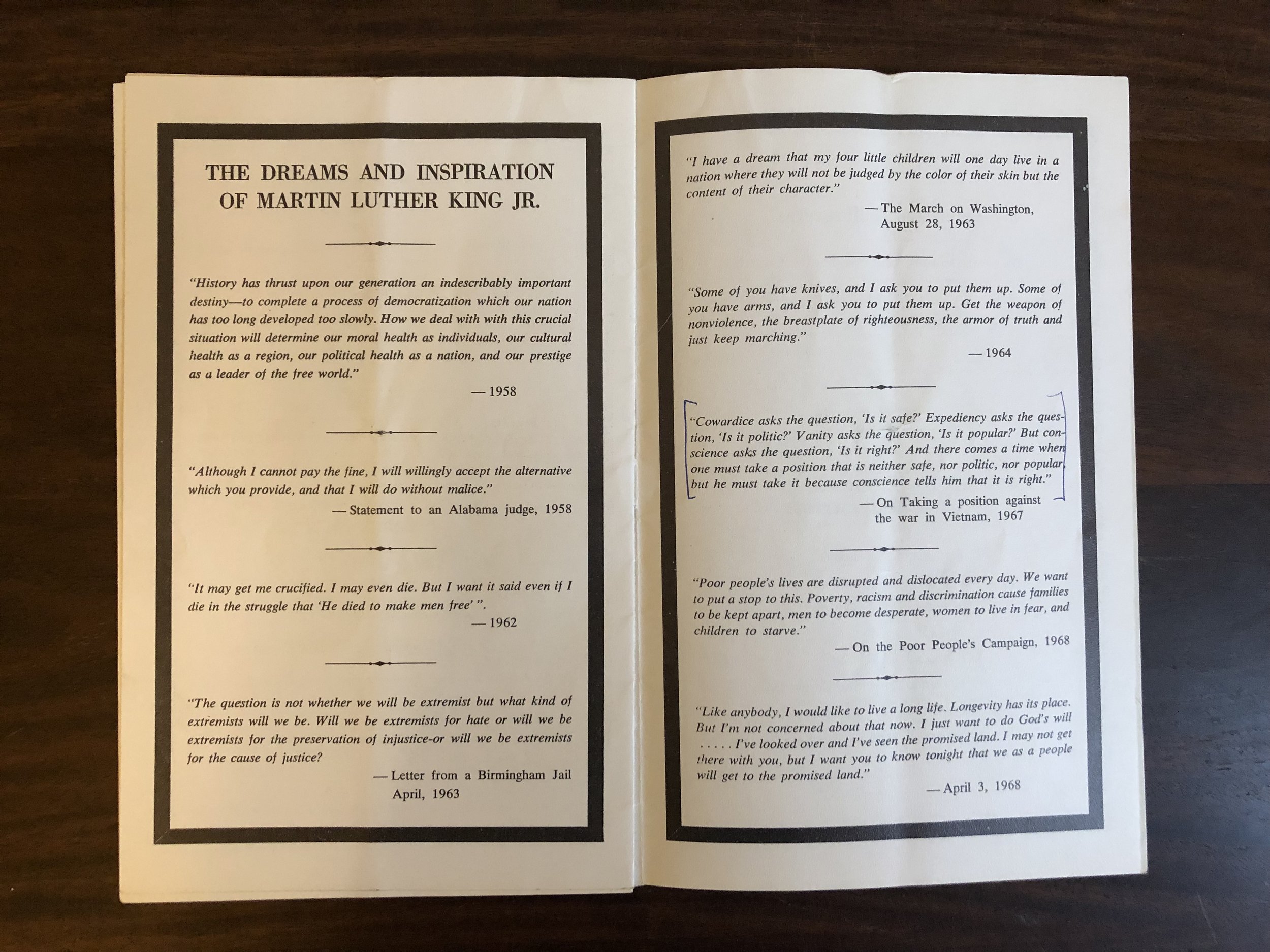

My father attended King’s funeral and described to me how, suffering from a canker sore, he had painted his sore lip with a purple-colored medicine called Gentian Violet. He told me how he cried and wept so much that his white button-down shirt ended-up stained by streaks of purple tears and (his words) “purple snot.” I have his ox-blood red admittance ticket.

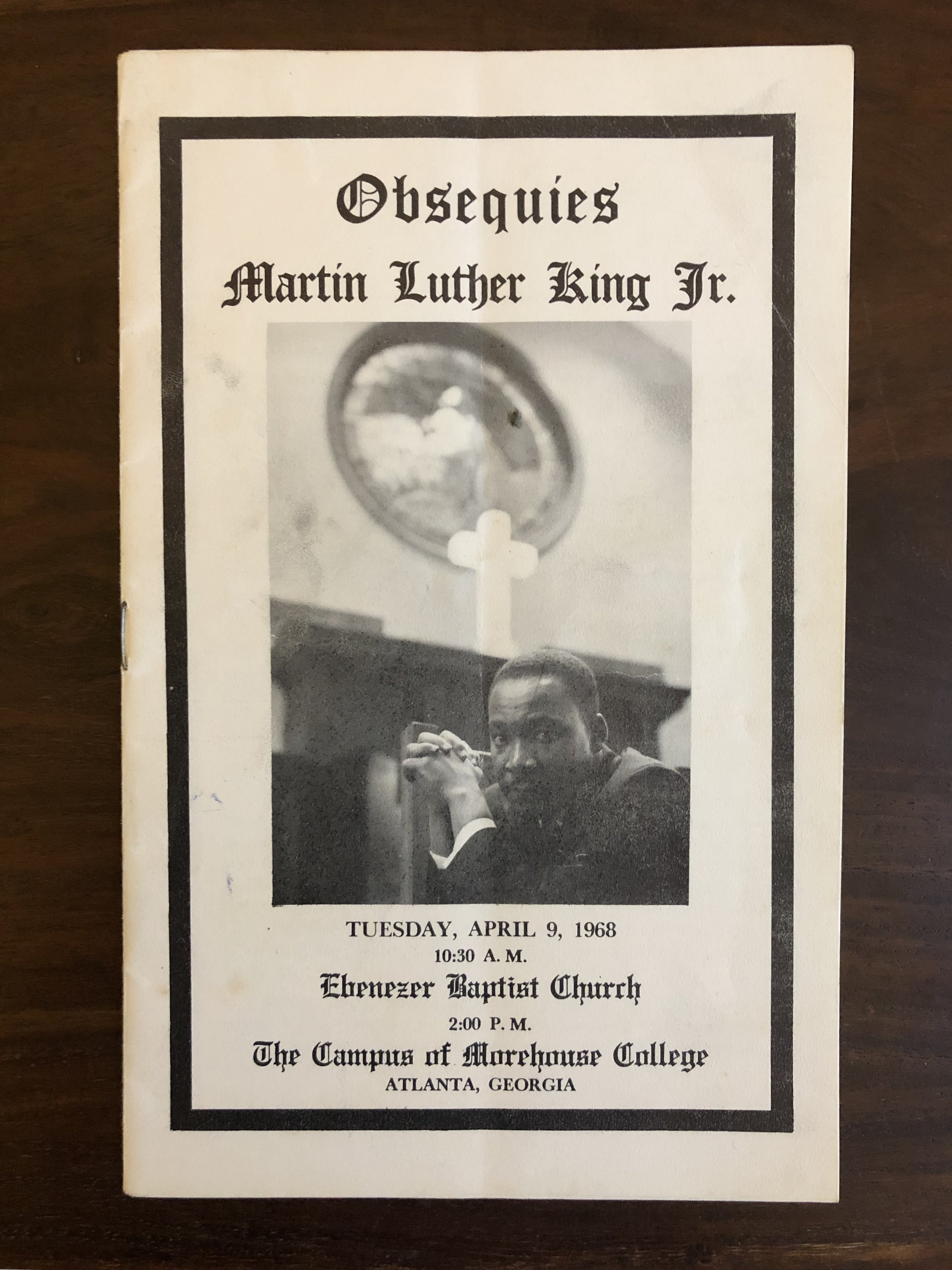

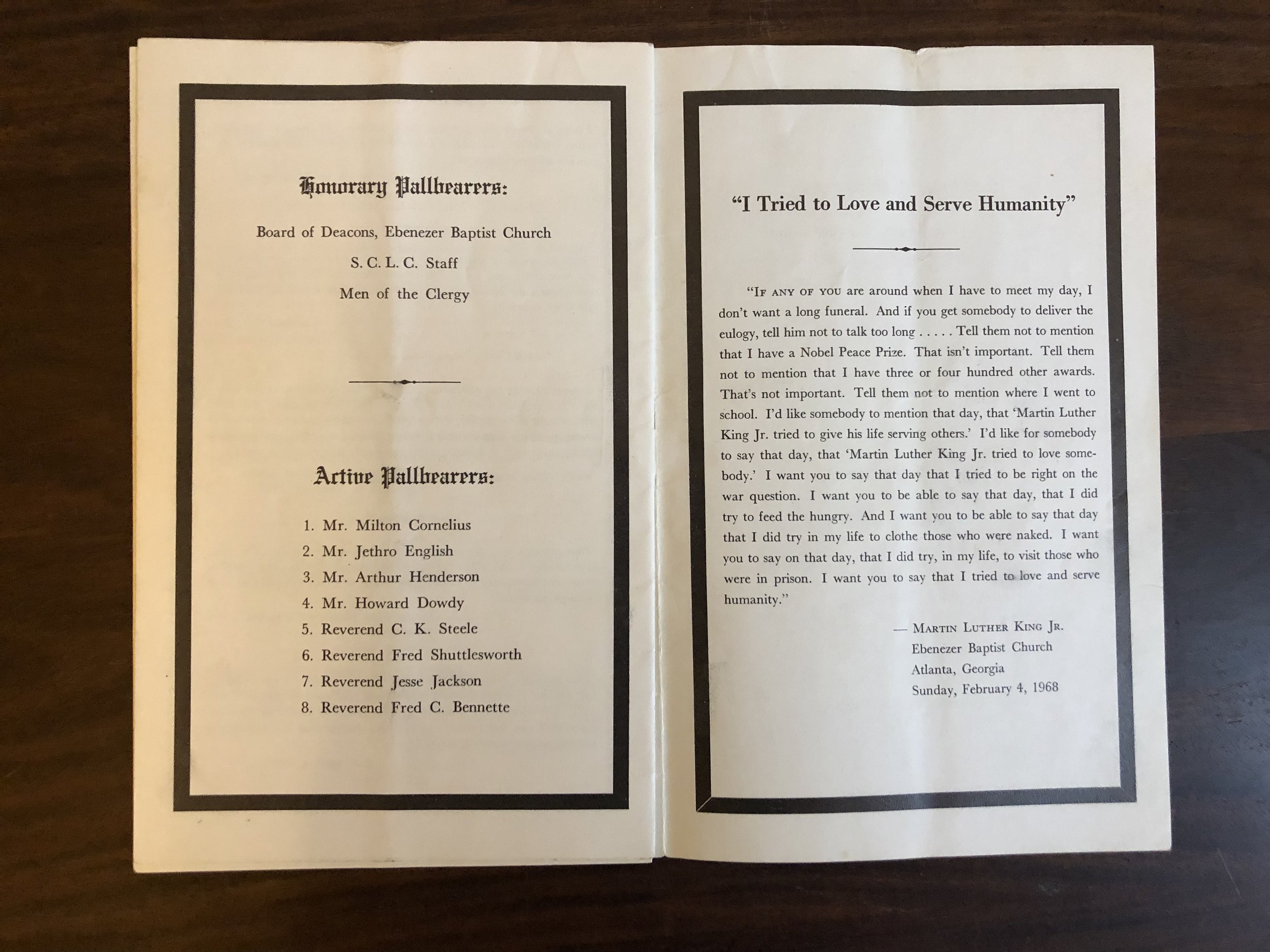

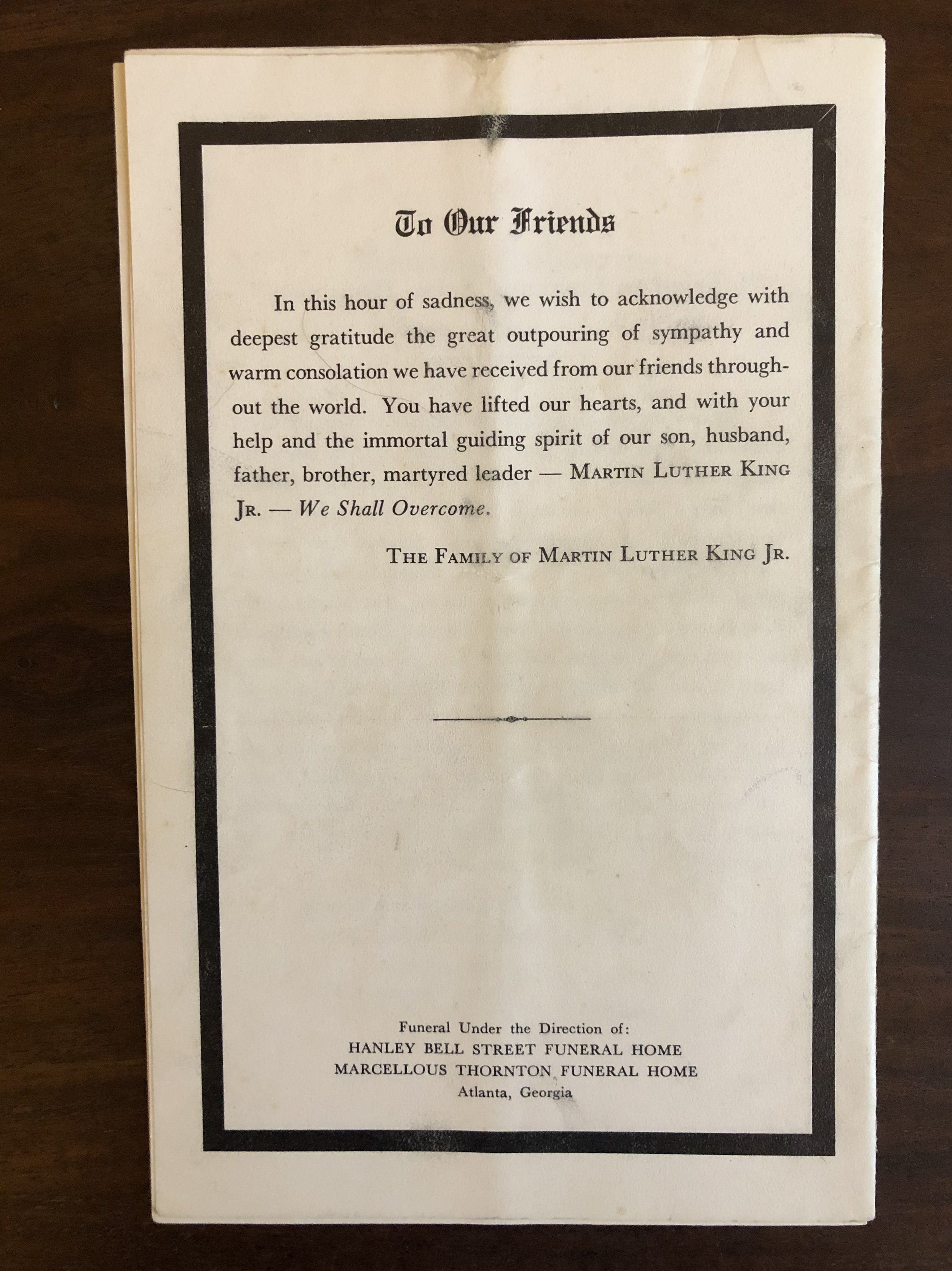

I have the Obsequies program from the service. My poor father, crying his eyes out, wiping his nose on his shirtsleeves. He was not afraid to feel.

The Trouble I’ve Seen: The Wrap-Up

On the Media

Throughout The Trouble I’ve Seen, my father probes the challenges of a white press reporting on black lives. While he takes himself and his own imperfect history to task, he saves his coldest view of the media for this last section of the book called “The Wrap-Up.” Writing ten years later, my father reflects back on what he saw in 1964:

When I refer to journalism I mean white American journalism, because the source of news in this country is overwhelmingly white. Can you remember the last (or first) time you heard a black reporter ask a question at a White House press conference? In Washington recently, an avowedly hard-nosed, liberal magazine called New Times appeared, not one name in its list of writers is black. As I write, I also have before me a book called Eye on the World, produced by CBS. The book features Walter Cronkite and offers ‘a kind of overview of the opening of the decade of the seventies.’ On the back cover are photographs of thirty-five CBS correspondents whose reports are covered in the book. No blacks, no Latins are among the men who covered “the major news events at decade’s dawn….”

I have seen the effect of this white control over the years in my work with all elements of the media. The effect ranges from today’s erosion of concern to past superficiality and arrogant assumptions that White Father Knows Best on racial issues. That a white conspiracy exists in the media to deliberately misrepresent black conditions has been charged. No conspiracy exists; none is needed….

[Our white journalists’]… view of American reality is determined by their commonality. They are well-educated men (with a few female counterparts) from white middle-to-upper class backgrounds who have become accustomed to very good incomes and who have developed a self-important belief in their capacity to act as arbiters of social justice. Unfortunately, none of their antecedents and achievements prepare them to comprehend the black American experience. This deficiency does not deter most of them from assuming that they can comprehend and interpret and set priorities of that experience. (249-50)

Last Thoughts

As I have hinted, my father was not a vessel of pastoral love; in the face of cruelty and ignorance, he hated back hard. My father burned with a passion that was nearly kiln-like; more Old Testament than New. Maybe he turned in on himself because professionally—in real time—he could not act on these feelings of anger, outrage. I stand in awe (and some jealousy) that this man, who did not control his temper at home, had the dignity and the professionalism not to get involved in fistfights—and worse—with the bigots and racists he encountered. He did not know how to kill them with kindness. Maybe only Jesus of the pastel illustrations of the Bible was large-hearted enough to absorb their rancid qualities while loving these creatures as brothers. He was a journalist, not an activist, and while he loved King and what he preached, he hated the men who spat on him and humiliated black people. He ends the book where we find ourselves today, still living in a divided country.

What I feel in my soul is that America will never be safe or sane or beautiful or free until the day comes when a statue honoring Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman is raised in front of the Neshoba County Courthouse. I don’t think that day is ever going to come. (272)

There are now, we know, plaques of dedication and remembrance for the three men in Neshoba County, though no statue in front of the courthouse, which would make the point too clearly that there had been no human laws governing what happened that night. What did a courthouse stand for in Mississippi in 1964? Not much.

My father went on to cover the poverty and race beats as a freelance writer, working for The Reporter, The Washington Post, The Nation, and others, spending half of my childhood flying to Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama. I waited for my father to bring things back from these dark and unjust places he visited. He brought back items like synthetic orange blossom perfume and raw sugarcane stalks wrapped in newspaper. Once he brought back cotton—cotton bolls on a branch with hard seeds in their centers—the crop of slavery and sharecropper misery. He told me of the conditions in the sugar cane fields and how men cut themselves deeply, sometimes fatally, on their scythes. He told me how a baby named Angela was born in Alabama without an anus because of the contaminated water her mother drank. He told me of eighteen people living on $127 a month in a two-room shack with no insulation. He told me of men who spent their lives pushing brooms. He told me of poverty I could not understand, even though the only photos displayed in our house were from his book, The American Serfs: a black man and a team of mules; two poor, shy black children, a girl about thirteen and a boy about seven, both in stained and ragged clothes, smiling at the photographer. I felt then what I could only now articulate: my father was divided between his family and the larger world that took him away from us when he was on assignment. He was always half in that other world, and that world did not have much to do with our Connecticut town and the concerns of its folk; what my family had was an affront to everyone who had less. We, too, were guilty living squarely in the upper echelons of the country’s inequities.

I missed my cantankerous father horribly the night Barack Obama was elected president. As I sat in a stranger’s house in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, watching the results come in, I wanted to tell everyone there that my father’s work had imperceptibly informed this election of a black man as President of the United States of America. His was a tributary that fed a Great River. But I kept quiet. Paul Good is ash now—ash and bone chips housed in a trunk somewhere in my Bedford-Stuyvesant basement storage room. I cannot part with his dust yet. It is not out of simple love for my father; love was not simple for him, but for when it concerned my mother and MLK Jr. My father never respected or loved another man as much as he respected and loved King. I imagine him viewing our current warped version of America with a further broken heart, if that is possible. That the American press is under attack as it is would absolutely enrage him, so much so that he might rise from the dead to right this heinous wrong. His ashes remain intact in case he chooses to reconstitute himself to set things straight. Though he would have scoffed at any idea of reincarnation or a full-body Christ-like resurrection, honestly, if anyone could come back from the dead, it would be him.

Works Cited

Good, Paul. The Trouble I’ve Seen: White Journalist/Black Movement. Howard University Press, 1974, Washington D.C.

Good, Paul. The American Serfs. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968, New York, New York

The Washington Post, March 22, 1965

Paul Good’s audio tapes are available for study at Emory University:

Paul Good Papers, 1963-1964

Emory University

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Atlanta, GA 30322

Regan Good is a poet, writer and teacher. Her first book of poems, The Atlantic House, was published by Harry Tankoos Books in 2012. A reviewer wrote: “The [book’s] dominant passages belong to a nearly timeless and expressively resonant realm. Good shows that a poet can be absolutely Romantic and remain absolutely contemporary.” Her second book, The Needle, will be published this fall. She lives in Brooklyn.